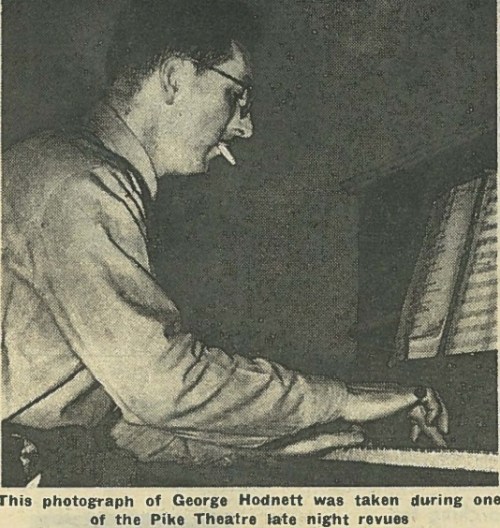

George Desmond Hodnett (Image Credit)

Next Sunday marks the centenary of the birth of George Desmond Hodnett, a man who lived a colourful life on several fronts. A guest on the first ever edition of The Late Late Show, he was part of the Bohemian set of 1950s Dublin, primarily known as a pianist and composer at the popular Pike Theatre. He was also a distinguished music critic with The Irish Times, with an unrivaled knowledge of jazz music. Known to many as Hoddy, a review of his appearance on The Late Late Show noted:

Hoddy brought to the show a splendid touch of almost baroque eccentricity. Now living in London, he was snaffled for the Late Late Show at a few hours notice. He entertained both studio audience and the viewer at home with a delightful line of talk about everything from the proceeding vulgarisation of O’Connell Street to his own view on copy-writing, a job he is currently doing in London.

A Dubliner by birth, he enjoyed a decidedly middle class youth, educated at the private Catholic University School on Leeson Street and Trinity College Dublin. He never finished his studies at Trinity, instead falling into the Dublin set of the day, frequently to be found in McDaid’s or the so-called Catacombs where drinking could continue into all hours.

Irish Times journalist Deaglan De Breadun remembered of him:

A talented composer and musician, he played jazz piano, trumpet and, of all things, zither. Perhaps he learnt to play it from his Swiss-born mother, Lauré. The instrument became briefly fashionable thanks to the Orson Welles movie, The Third Man and, at the time, George was probably the only zither-player in the country.

He cut a most unusual shape, and Frank Kilfeather recalled that “from his dress, to his conversation, to his peculiar habits, Hoddy was a character. If he hadn’t existed, the most brilliant fiction writer couldn’t invent him. He always wore two overcoats and two jumpers, even in the middle of summer.”

In the 1950s, Hoddy was a loved part of the repertoire of the Pike Theatre, penning and performing satirical tunes for revues at the venue, where he worked as resident pianist. I won’t say much about the Pike Theatre, because it will be returned to again on the blog, but it was a necessary institution in the Ireland of its day that pushed boundaries and offered a platform to sometimes sidelined voices. In the words of Brian Fallon, writing about the 1950s (a decade that is often wrongly considered a grey one in Irish culture), “most of the laurels for the decade belong to the gallant little Pike: for its staging of Behan’s masterpiece, for mounting Beckett’s Waiting for Godot the following year and for its 1957 performance of Tennessee Williams’s The Rose Tattoo which led to its actors appearing in court under a police prosecution for indecency.” Located in Herbert Lane, the theatre was the great vision of Alan Simpson and Carolyn Swift. It was making an impact at a time when the mainstream theatre world was offering little. In Spiked: Church-State Intrigue and The Rose Tattoo, it’s noted wryly that “when the Abbey burned down in 1951, it was popularly joked that the fire was the first flame of any kind to light the place up for many years.”

One great Hoddy original was Monto, popularly known now as ‘Take Her Up To Monto’. In his own words, it was a satire of many folk songs of its day, though he noted in one interview that its popularity reached a point “when it has become the folk song it originally aimed at satirising.”

If you somehow haven’t heard it here it is in all of its glory:

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.