Gabriel Lee is the only member of Eoin O’Duffy’s Pro-Franco ‘Irish Brigade’ to be commemorated with a public memorial in Ireland. A small plaque in Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral marks the fact that he died fighting with the Fascist forces in Spain in 1937.

This is in stark contrast to the 20+ plaques and memorials across the island to Irishmen who fought with the International Brigades in defence of the Spanish Republic.

Gabriel Lee was born on 21 May 1904 in Kilcormac (formally known as Frankford), a small town in County Offaly between Tullamore and Birr. His parents were James Lee, a Sergeant in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), and Elizabeth Lee (née Conroy).

Gabriel Lee, birth certificate 1904.

At the time of the 1911 Census, Gabriel Lee was living with his large family at 22 Townsend Street, Birr, County Offaly.

It is claimed that Gabriel Lee was a member of the Pre-Truce IRA although he only would have been in his mid to late teens during the War of Independence (1919-1921). Taking the Pro-Treaty side in the Civil War, he enlisted with the National Army on 25 March 1922 at Marlborough Hall, Dublin. When the Irish Army census was conducted in November 1922, he was serving with the 1st Battalion, South-Western Command at Mallow, County Cork. His home address was given as 45 Lower Drumcondra Road, Dublin.

Gabriel Lee, 1922 Army census.

During the early 1930s, Gabriel Lee served as Vice-Chairman of Fine Gael’s Dublin North West Exectutive and Vice-Divisional Director of the League of Youth, Dublin. He was known to his comrades as Gabe Lee.

James Lee and and his son Gabriel Lee photographed on O’Connell Street, 1934. Credit: ‘Arthur Fields: Man on Bridge’

A committed anti-Communist and devout Catholic, he left Galway with Eoin O’Duffy’s ‘Irish Brigade’ for Spain on 12 December 1936.

Gabriel Lee was injured by shellfire at Ciempozuelos on 13 March 1937 and was brought to Griñón Hospital, Madrid. Eoin O’Duffy recalled in correspondence that Lee had tried to “raise his hand in the Fascist salute” in his hospital bed. Apparently his “final request” was to be buried in a green shirt as retold in Fearghal McGarry’s 2007 biography of Eoin O’Duffy. This indicated his strong loyalty to O’Duffy who had broken away from Fine Gael in 1935 to form the National Corporate Party and the Greenshirts (military wing).

Gabriel Lee died of his wounds on 20 March and was buried in Cáceres, Spain with several other members of the ‘Irish Brigade’.

Gabriel Lee. The Sunday Independent, 12 June 1960.

The Irish Brigade Headquarters, 12 Pearse Street, Dublin released a statement three days after Lee’s death to the Irish Independent (23 March 1937) saying that:

To those who scoff at the motives impelling such sacrifices we say that charity should dictate that only good be spoken of such bravery men. We in this Headquarters know how little inducement or hope of worldly gain was offered to the members of the Irish Brigade. We know their motives, and we know that the souls of these men are with God because they died for God.

Historian Robert Stradling believed that Gabriel Lee was the only individual who fought with Eoin O’Duffy’s ‘Irish Brigade’ in Spain to have a public memorial in Ireland. In Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral, there is a small plaque on a pew dedicated to his memory which I photographed over the weekend.

Gabriel Lee plaque, Pro-Cathedral Dublin. Credit – Sam, Come Here To Me! August 2018.

Gabriel Lee plaque, Pro-Cathedral Dublin. Credit – Sam, Come Here To Me! August 2018.

In total, I believe that 10 pro-Franco Irishmen were killed in action during the conflict. I have collected these dates, names and addresses from contemporary newspaper articles and death certificates via Irishgenealogy.ie:

1937-02-19 – Captain Thomas Hyde (40) of Ballinacurra, Midleton, Cork – killed at Ciempozuelos in friendly fire incident – buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-02-19 – Daniel Chute (27) of Boherbee, Tralee, County Kerry – killed at Ciempozuelos in friendly fire incident – buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-03-13 – John MacSweeney (23) of Mitchell’s Crescent, Tralee, County Kerry – died from wounds received on Madrid Front – buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-03-13 – Bernard Horan (23) of Mitchell’s Crescent, Tralee, County Kerry – died from wounds received on Madrid Front – buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-03-20 – Gabriel Lee (32) of 45 Lower Drumcondra Road, Dublin – died from wounds received on Madrid Front – buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-03-21 – Thomas Foley (30) of 16 Mary Street, Tralee, County Kerry – died from wounds received on Madrid Front. Refs: (1)(2)

1937-07-15 – Michael Weymes (29) of Mullingar, County Westmeath and later 2 Belton Park Gardens, Donnycarney, Dublin – killed at Villafranca del Castillo on the Mardrid Front- buried in Cáceres, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1938-08-? – Patrick Dalton of Pilltown, County Kilkenny- killed in Spain. Incorrectly listed as P. Dolan in one source. Described as Irish student in Spain studying to be a priest. Not Patrick Dalton (1897-1956) of Waterford/Dublin who also served in Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

1938-09-10 – Daithi Higgins (21) of Ballyhooly, County Cork – killed at the Battle of the Ebro fighting with the Spanish Foreign Legion. Refs: (1)(2)(2)

1938-10-? – Austin O’Reilly of Kilmessan, Co Meath – killed at the Battle of the Ebro. Refs: (1)(2)

Five of the Irishmen on the Irish Brigades’ ‘Roll of Honour. The first four were killed in action, the fifth died of diseases contracted in Spain.

I have also calculated that about 21 of Eoin O’Duffy’s men also died in at home or abroad from diseases contracted while serving with the ‘Irish Brigade’:

1937-04-?? – John Walsh of Midleton, County Cork – died in Spain and buried in Cáceres. Refs: (1)(2)

John Walsh, Irish Independent (05 April 1937)

1937-06-?? – Thomas Troy of Tulla, County Clare – died in Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

Thomas Troy, Irish Press (30 June 1937)

1937-07-?? – Eunan McDermott of Erne Street, Ballyshannon, County Donegal – died in Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

Eunan McDermott, Irish Press (12 July 1937)

1937-07-24 – John McGrath (22) of Lenaboy Avenue, Salthill, County Galway – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

John McGrath, Irish Independent (27 July 1937)

1937-08-20 – Thomas Doyle of Roscrea, County Tipperary – died in Salamanca, Spain. Refs: (1)(2)

Thomas Doyle (Longford Leader, 04 Sep 1937)

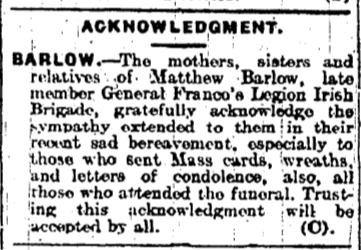

1938-01-08 – Matthew Barlow (44) of Chapel Street, County Longford – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

Matthew Barlow, Longford Leader (22 January 1938)

1938-02-02 – John Cross (32) of 49 William Street, County Limerick – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

Jack Cross, Irish Independent (04 February 1938)

1938-02-09 – Patrick Dwyer (32) of 19 Sheehy Terrace, Clonmel, County Tipperary – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

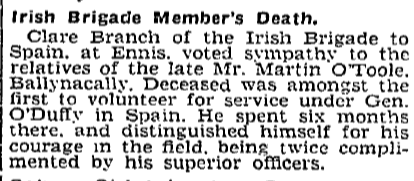

1938-09-17 – Martin O’Toole (28) of Ballynacally, County Clare – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

Martin O’Toole, Irish Independent(21 September 1938)

1939-03-04 – Patrick Collins (33) of Bandon, County Cork – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

Patrick Collins, Sunday Independent (12 March 1939)

1939-03-27 – Thomas Slater (30) of 47 Garrymore, Clonmel, County Tipperary – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

Thomas Slater (Irish Independent, 30 March 1939)

1939-04-12- James Doyle (22) of Boherglass, Clonlong, County Limerick and later 63 High Street, Thomondgate, County Limerick. Died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

James Doyle, Limerick Leader (22 April 1939)

1939-06-29 – Francis Maguire (32) of Belgium Square, Monaghan Town, County Monaghan – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

1939-09-13 – Laurence Heaney (37) of 32 North Great George’s Street, Dublin – died in IRL. Refs: (1)(2)

1940-02-04 – William Tobin (37) of 2 Abbeyside, Cashel, County Tipperary – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

William Tobin, Irish Independent (8 February 1940)

1940-02-05 – Philip Comerford (25) of Kells, County. Kilkenny – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

Philip Comerford, Irish Independent (13 February 1940)

1940-03-23 – John McCarthy (37) of Castletownbere , County Cork – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

John McCarthy, Irish Independent (6 April 1940)

1940-03-26 – Austin Hamill (33) of Hill Street, Monaghan town, County Monaghan – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

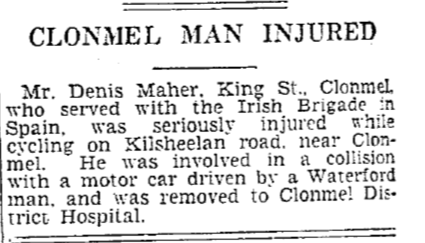

1940-04-25 – Denis Maher (36) of 25 King Street, Clonmel, County Tipperary – road traffic accident in IRL. Refs: (2)

Denis Maher, Irish Independent (26 April 1940)

1940-06-?? – Thomas Gunning of County Leitrim – died in Germany Refs: (2)

?? – Frank Nevin of 82 St. Lawrence Road, Clontarf Dublin – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

Couldn’t find obit in newspapers but thought this was interesting re: Frank Nevin (Irish Independent, 3 April 1937)

?? – Michael O’Donoghue of County Galway – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

?? – Patrick McGarry of Newtownforbes, County Longford – died in IRL. Refs: (2)

–

(1) Listed as one of the 21 men who “lost their lives” while serving with the Irish Brigade. The Irish Independent, 03 May 1939

(2) Listed as one of the 33 “deceased members” of the Irish Brigade. The Irish Independent, 16 October 1940

Thank to Gerard Farrell for additional documents and information.

Read Full Post »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.