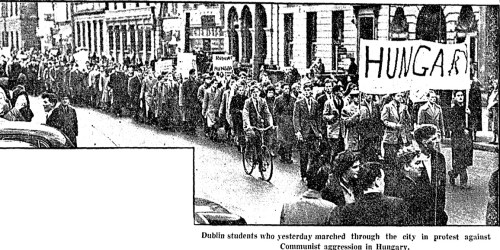

There are few things as magical about Dublin as a New Year announcing itself through the bells of Christchurch Cathedral. Ideally, you have a pint from the Lord Edward in your hand or someone in your arms as you take it in.

A visit to the belfry is possible, and is an experience we Dubliners shouldn’t leave entirely to visitors. The oldest of the bells in usage today dates from 1738, with a number coming from the time of the Roe whiskey distillery funded restoration of the cathedral in the nineteenth century.

One place you can hear the bells is The Chieftains remarkable Christmas album, The Bells of Dublin. Released in 1991, it both begins and ends with the sound of the church bells ringing. As John Glatt writes in his biography of the band, “intrepid sound engineer Brian Masterson crawled out on to the roof of Christchurch and set up various microphones to record the majestic peels of the bells. For the recording Moloney [Paddy Moloney of the band] joined the bell ringers in the belfry to play his part.”

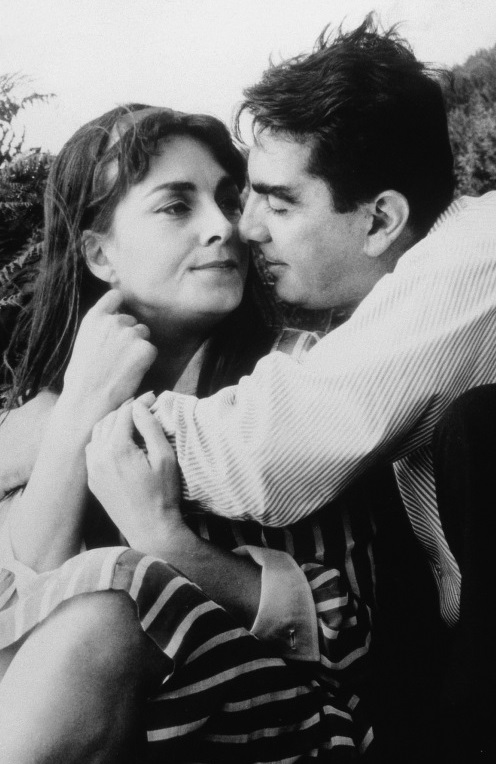

The Bells of Dublin cover (RCA Victor)

Coming four years after The Pogues and Kirsty MacColl gifted the world Fairytale of New York, it once again demonstrated that Irish traditional music could hold its own when it came to Christmas magic. The Chieftains had been a mainstay of the Irish music scene since the 1960s, though unlike The Pogues who followed they were much more about the tradition. Paddy Moloney would recall:

I had great faith that one day what we did best– playing traditional Irish music– was going to soar, and I wasn’t going to be stepping down the ladder by changing the style. Our first concert in the Albert Hall was just music– no flashing lights or smoke screens, and we didn’t have dancers or singers– so to see the crowd dance around the theatre, coming back for encore after encore, was just magic. There were tears in our eyes that night. We didn’t realize that people from the rock world were listening to us, like The Rolling Stones, Marianne Faithfull and Paul McCartney, so the whole social thing started to develop and word got out. We were taking our time and gradually creeping in. Then in ’75, we were on the front page of Melody Maker as Group of the Year. That was huge!

The album included guest appearances from Elvis Costello, Marianne Faithfull, Kate and Anna McGarrigle and Jackson Browne among others. Browne’s contribution, which he wrote, is a rejection of the crass commercialisation of Christmas as he sees it, and a reminder of what he feels Jesus stood for:

Well we guard our world with locks and guns

And we guard our fine possessions

And once a year when Christmas comes

We give to our relations

And perhaps we give a little to the poor

If the generosity should seize us

But if any one of us should interfere

In the business of why there are poor

They get the same as the rebel Jesus

The St. Stephen’s Day Murders, on which Elvis Costello appears, captures the cabin fever of the season with great wit:

I knew of two sisters whose name it was Christmas

And one was named Dawn, of course the other one was named Eve

I wonder if they grew up hating the season

Of the good will that lasts till the Feat of St. Stephen

For that is the time to eat, drink and be merry

Until the beer is all spilled and the whiskey has flowed

And the whole family tree you neglected to bury

Are feeding their faces until they explode.

The album was recorded primarily at the Windmill Lane Studios. Though primarily associated with U2, ,acts as diverse as David Bowie, New Order, Erasure and Sinead O’Connor have also recorded there.

The Chieftains output includes an acclaimed collaboration with Van Morrison, a tribute to the heroic fighting men of the San Patricio Battalion and the story of the 1798 rebellion. For me, The Bells of Dublin remains their finest hour, and it should be essential listening this week.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.