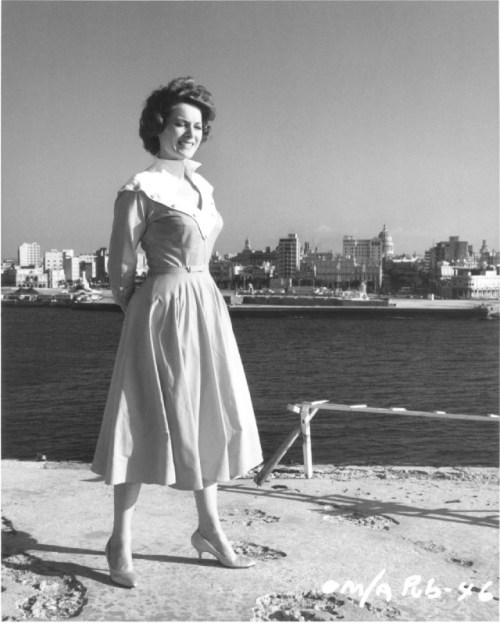

Liam Sutcliffe at the Spire, previously published on CHTM in Dear, Dirty Dublin series.

Whether or not the removal of Admiral Horatio Nelson from the Doric column on which he stood for so long was a good or bad thing will be eternally debated by Dubliners.

In the immediate aftermath of the blast, there were mixed reactions too. An American journalist wrote home that “Dublin’s mood was one of gaiety. Crowds jostled and joked around the police cordons at the scene.” By comparison, The Economist condemned the blast, as “Nelson’s fall may be good for a laugh; but it is comical only by the greatest good luck. Post-colonial Dubliners being safely in their beds by 1.30 a.m, nobody was hurt.”

In recent years I got to know Liam Sutcliffe, one of the men responsible for the bombing of the Nelson Pillar, who died last Friday. When I wrote The Pillar in 2014, he signed more copies of the book than I could dream of. He also had a remarkable ability to hear about any talk on the Nelson Pillar in the city. On one occasion, I got a good laugh out of seeing him stroll into Store Street Garda Station where I was giving a lecture for the Garda Historical Society on the Golden Jubilee of the blast. There may have been familiar faces in the room.

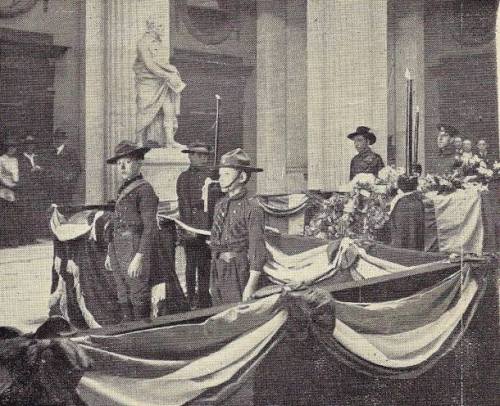

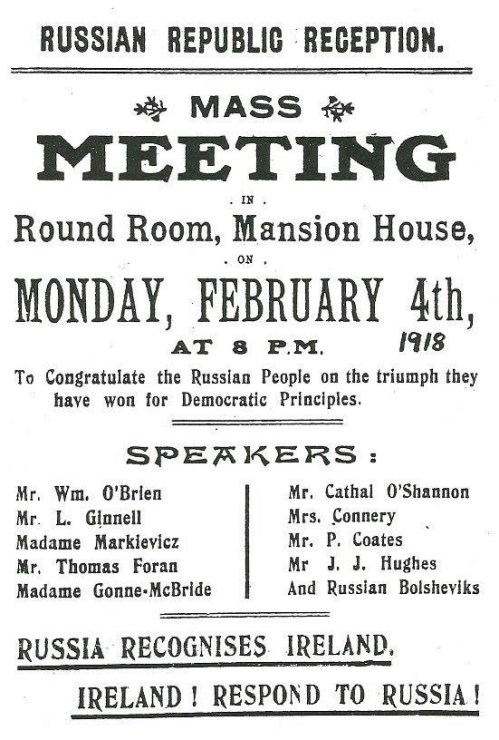

Liam Sutcliffe’s time in the republican movement did not begin or end on 8 March 1966. From Dublin’s south inner-city, he joined the IRA in 1954, shortly before the ill-fated Border Campaign. He was to become an IRA agent inside Gough Barracks in Antrim, gathering important information. Liam was among the (primarily young) men who followed the charismatic Joseph Christle out of the organisation; the ‘Christle Group’ were viewed as dissidents by IRA leadership, soon launching their own attacks north of the border. Joseph Christle had been among the students who climbed to the top of the Nelson Pillar in October 1954 and hung a banner of Kevin Barry from the viewing platform, carrying with them instruments they hoped would help remove Nelson. On that occasion, efforts to remove the Admiral failed, but his days were numbered. Gough, William and George could tell him as much.

Liam remained active in republican politics after the destruction of the Nelson Pillar, joining Saor Éire in 1970. In this capacity, he “was involved in the arming and training of the Nationalist Defence Committees in Belfast and Derry. He became a leading volunteer in the group, active in many of its engagements.” Saor Éire’s manifesto proclaimed that “in the Six Counties today the Butchers are at work again. The ghetto uprising of the Catholic-Nationalist population is the latest round in the Irish struggle for self-determination. But the rulers in the Free State are not in the least interested in the people North of the Border.” For Liam, there could be no question about the need to assist the besieged nationalist population.

In recent years, Liam was frequently to be found at commemorations honouring friends who had given their lives in the 1960s and 1970s, but he was also politically active in campaigns like that to Save Moore Street. A regular in Tommy Smith’s wonderful establishment, Grogans on South William Street, he had a great love for discussing history and politics and a wonderful friendly manner, not to mention a fine sartorial touch, never shying away from a pink shirt. He will be missed by many, and I will think of him every time I pass O’Connell Street.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.