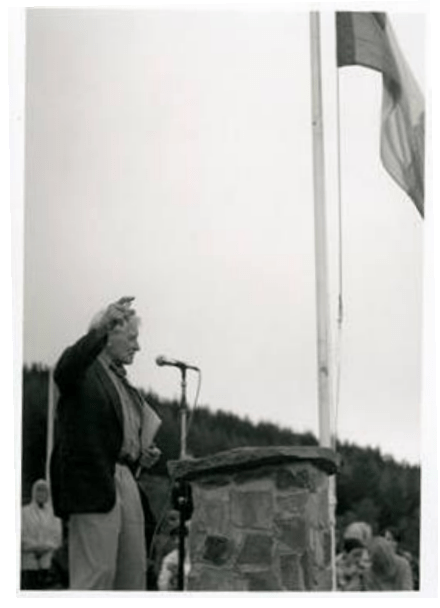

C.L.R James speaking in Trafalgar Square, London. (1935)

Whether cricket or Marxism is your bag, C.L.R James is a towering figure in each world. They are, I concede, two worlds that tend not to meet. His 1963 memoir Beyond a Boundary, which he himself described as “neither cricket reminiscences nor autobiography”, is widely regarded as one of the finest books ever written on any sport. He maintained that “cricket is first and foremost a dramatic spectacle. It belongs with theatre, ballet, opera and the dance.”

Born in Trinidad in 1901, Cyril Lionel Robert James made important contributions in many fields of life. As a historian, he penned The Black Jacobins, an acclaimed history of the Haitian Revolution, and he would make many important intellectual contributions to the field of postcolonial studies. A lifelong political activist, he was highly critical of the Soviet Union under Stalin, and was aligned with Trotskyist movements in the turbulent 1930s. He arrived in Britain in 1932, taking up a job as cricket correspondent with the Manchester Guardian and throwing himself into political activism in London.

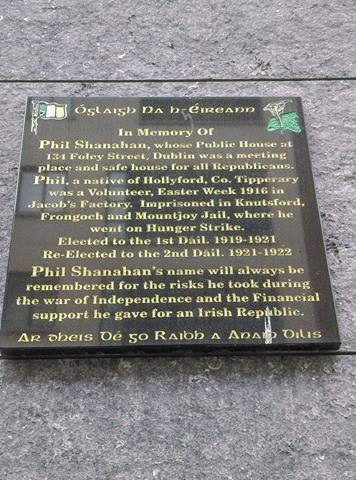

In 1935, he arrived in Dublin, lecturing on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Here, he befriended Nora Connolly O’Brien, the daughter of James Connolly, and encountered opposition from some surprising quarters.

The response to the invasion of Ethiopia:

An imperial grab for Africa, Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia was condemned by the League of Nations by fifty votes to one (the single dissenting voice being the Italians themselves). Despite condemnation, little real action was taken by the European powers after the commencement of the invasion in September 1935, and the annexation of the country allowed Mussolini to proclaim that “the Italian people have created an empire with their blood. They will fertilize it with their work.” The following year, Mussolini would send men and planes to Spain to crush democracy there, but 1935 demonstrated his disregard for the sovereignty of other nations to all who were paying attention. From Dublin, Éamon de Valera had been one of the few political leaders to loudly condemn the actions of the Italians, warning the League of Nations that “if on any pretext whatever we were to permit the sovereignty of even the weakest state amongst us to be unjustly taken away, the whole foundation of the League would crumble into dust.”

James, then a member of the Independent Labour Party, wrote extensively on the fascist invasion, writing in The New Leader:

Let us fight against not only Italian imperialism, but the other robbers and oppressors, French and British imperialism. Do not let them drag you in. To come within the orbit of imperialist politics is to be debilitated by the stench, to be drowned in the morass of lies and hypocrisy.

He was a founding member of the International African Friends of Ethiopa, and in this capacity lectured all over Britain, speaking at a protest rally in Trafalgar Square on the need for solidarity. In December 1935, he arrived in Dublin to address a meeting opposing Italian fascist aggression, finding a weak left but some welcoming faces. James would later recall that “he didn’t really understand what it meant to be revolutionary until he went to Ireland.”

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.