In a post-Sackville Lounge world, I have little reason to wander down Sackville Place, the street to the side of Clery’s department store. Indeed, Clery’s itself is now no more, and last winter some its historic signage disappeared without trace.

Thankfully still affixed to the building is a plaque in honour of Paweł Edmund Strzelecki (1798 -1873). An explorer and geologist of considerable fame abroad, Strzelecki’s contribution to the distribution of Famine Relief in the west of Ireland during the Great Hunger is remembered on the plaque in English, Polish and As Gaeilge. It is a beautiful tribute, unveiled in March 2015 at a ceremony that was attended by members of the Polish community in Ireland and representatives from the city of Poznan.

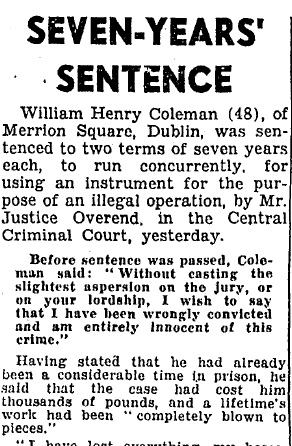

Sackville Lane, March 2017.

There are many stories of international assistance and interventions in the story of Ireland’s Great Hunger. Some, like the assistance of the Choctaw Nation of displaced Native Americans, have been well remembered and commemorated. There were also numerous interesting individuals who were moved to action by the calamity in Ireland; French chef Alexis Soyer would establish a soup kitchen at the site of what is now the Croppies Acre memorial, feeding thousands. Strzelecki’s story is much less widely known than Soyer or the Native Americans however, but was brought to prominence by the Polish community in Ireland in recent times.

Born in Głuszyna (near Poznan) in 1797, Strzelecki lived a remarkable life on a number of fronts. Firstly, he served within the Prussian army for a period, though his service was brief, and he was instead destined for exploration. Denis Gregory, author of Australia’s Great Explorers, has noted that traveling around Europe he developed “an interest in science, agriculture and meteorology. History notes that he had a look around the mines in Saxony and Mount Vesuvius in Italy.” Such travel and intellectual curiosity was the preserve of only a small wealthy elite of course,and his travels were not confined to the European continent. He traveled widely in North and south America, and made it to New Zealand in the early months of 1839.

As an explorer, he is best remembered for his time in Australia. On the invitation of the Governor of New South Wales, Strzelecki conducted a mineralogical and geological survey of the the Gippsland region, where he discovered gold in 1839, yet his finding was suppressed by the Governor, who “feared the social disruption that a gold rush would inevitably cause in what was still demographically a convict colony.” Strzelecki would chronicle some of the remotest parts of Australia, and an impressive monument in his honour stands today in Jindabyne, New South Wales.

Sackville Lane, March 2017.

The failures of the British State in relation to the suffering of the Irish peasantry throughout the years of the Great Hunger is well documented. Sir Charles Trevelyan, a senior British civil servant and colonial administrator, believed that:

The judgement of God sent the calamity the teach the Irish a lesson,that calamity must not be too much mitigated…The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.

Such beliefs were not those of some hack, but rather a political administrator who could directly impact on the lives of the suffering masses. As Melissa Fegan has noted, Trevelyan and many of those around him were “convinced that the Famine was providential in nature, and even if political economy had not forbidden a radical intervention in the markets, who could challenge the hand of God?”

Despite such abhorrent views from some in authority, huge sums of money were raised for the purpose of Famine relief in Britain. This came from migrant Irish workers, Quakers, sympathetic businessmen and a wide cross section of society. The most significant body to operate in Ireland during this period was the British Relief Association, described by historian Christine Kinealy as the body which provided “the greatest amount of relief” in Ireland. It was for this body that Paweł Edmund Strzelecki laboured over a period of eighteen months, overseeing the distributing of relief in the west of Ireland, which was worst affected by the failure of the potato crop. At first, Strzelecki had responsibilities for the Mayo, Donegal and Sligo regions, and he was one of only twelve agents working on behalf of the British Relief Association in Ireland. As Enda Delaney has noted, “his confidential reports to the committee in London chronicled the descent of this region into complete starvation”. He wrote that:

The population seems as if paralysed, and helpless, more ragged and squalid; here fearfully dejected…stoically resigned to death; then, again, as if conscious of some greater forthcoming evil, they are deserting their hearths and families. The examination of some individual cases of distress showed most heart-breaking instances of human misery, and of the degree to which that misery can be bought.

In Dublin,things were miserable too. The Freeman’s Journal reported in May 1847 of a woman named Eliza Holmes, arrested by the police while begging on Sackville Street with her dead infant child in her arms. Refugees from the country side flooded into the urban centres. Many were, of course, destined to leave the island via the port of the capital. As David Dickson has written,this was in many ways to the benefit of the city, as “if access to either Britain or North American ports had been denied to Famine refugees during the late 1840s, Dublin would have been catastrophically overwhelmed by those seeking institutional protection”.

Strzelecki both lived and worked in the Sackville Street area during some of his time in Ireland, basing himself in the Reynold’s Hotel in Upper Sackville Street. For a time he himself was incapacitated by ‘Famine Fever’, but he continued to carry out important administrative work from Dublin.

For his troubles, the Polish explorer was made a Knight Commander of the Honour of Bath in 1848. Remarkably, so too was Trevelyan. Unlike Trevelyan, Strzelecki received and sought no payment for his work in Ireland during the Great Hunger. One early historian of the period would later note that “the name of this benevolent stranger was then, and for long afterwards, a familiar one if not a household word in the homes of the suffering poor.”

Strzelecki died in October 1873, and he was buried in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery. In 1997, his remains were returned to Poland. It is fitting that he is remembered on the streets of Dublin today.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.