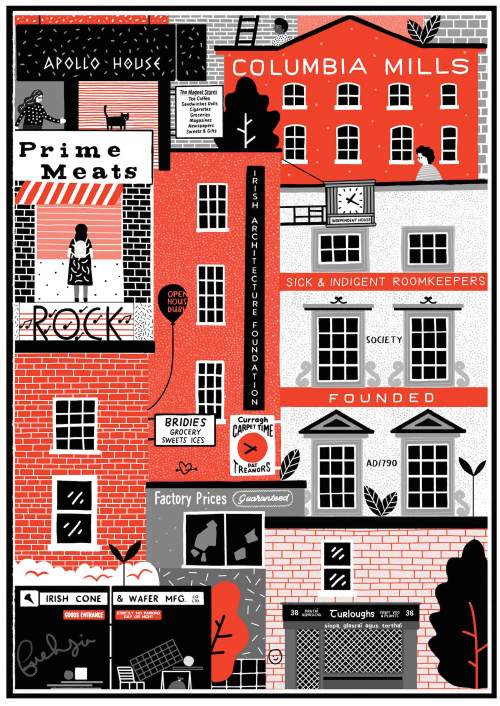

This article was first published in Rabble magazine. Given the on-going occupation of Apollo House by activists, it seems right to post it here. You can donate to ‘Home Sweet Home’ by clicking here.

Apollo House, 17 December 2016.

Apollo House, an unpopular architectural relic of the 1960s, has been closed for several years now. At the time of its construction, it was just one part of what historian Erika Hanna has called “a matrix of speculative office blocks, which dominated the skyline and reshaped the landscape of the city.” Both it and the neighbouring Hawkins House have been earmarked for demolition, but in recent days the occupation of the building by housing activists has grabbed national and international attention.

The decade when Apollo House was constructed witnessed very real agitation on the issue of housing in Dublin, with the establishment of the Dublin Housing Action Committee and similar organisations in other Irish cities. Many of the key players involved in this movement were important figures in revolutionary political circles at the time, and the housing campaigns of the 1960s utilised direct action tactics which often succeeded in grabbing the headlines and the attention of authorities. Just today, a letter appeared in The Irish Times from Márín de Burca of the DHAC, expressing her support to the occupiers:

As a founding member of the old Dublin Housing Action Committee, I applaud the actions of the Home Sweet Home group and others who have taken over Apollo House for the homeless. I am sure that they know quite well, as we did in the 1960s, that this is not a long-term solution but in the short-term it puts a roof over the heads of families. There is absolutely no reason why support is an either-or proposition. It is possible to support the short-term option while fighting fiercely for the basic right of citizens to a permanent secure home. In an era when it seems that only self-interest will bring people out on the streets in protest, it is heartening to see that there are still some who look beyond the cost to themselves and will fight for right and justice for those less privileged.

Masthead of DHAC newsletter (Irish Left Archive, Cedar Lounge Revolution)

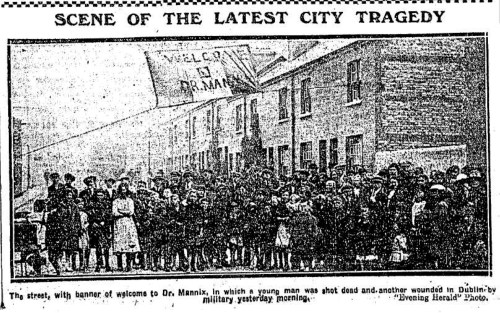

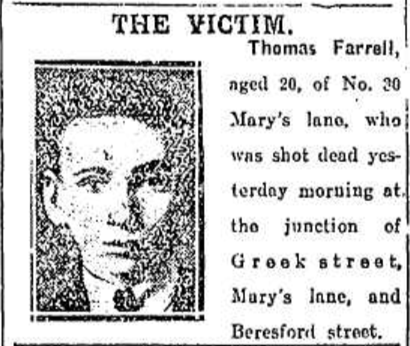

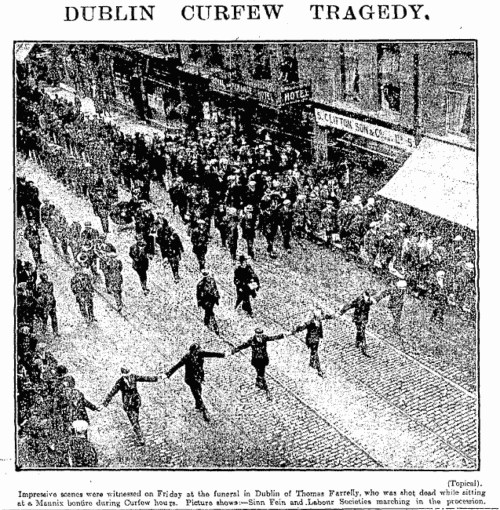

.By the early 1960s, despite some substantial suburban construction projects in the decades prior such as those in Cabra and Ballyfermot, a significant number of people in inner-city Dublin were still living in outdated and dangerous tenement accommodation. Two tenements collapsed within weeks of one another in June 1963, with two elderly Dubliners and two schoolchildren losing their lives. Images of a collapsed tenement on Bolton Street shocked the public on June 2nd, and by the end of the month the media were reporting that since the disaster “156 houses have been evacuated because they were in a dangerous condition. This has necessitated the rehousing of 520 families.”

Families were housed in the old living quarters of Dublin Fire Brigade stations or moved temporarily into suburban Dublin, while the city even considered utilising prefabs to deal with the crisis. By no means were such horrors confined to Dublin, and indeed north of the border housing rights and access to a decent standard of accommodation for all was a central motivating issue for the Civil Rights movement there.

In May 1967, the Dublin Housing Action Committee was born, the brainchild of left-republican activists, and as Tara Keenan-Thomson has written in her study of women in Irish street politics historically, “the main personalities in the group were Máirín de Burca, a young socialist (…) who had returned to Sinn Féin after it had shown signs of contemplating social action, and Prionsias de Rossa, another young republican socialist”. In addition to this left-republican element, the movement also drew in members from a wide spectrum of leftist parties and community groups. Among its key demands were “the repair of dwellings by Dublin Corporation where landlords refuse to do so” and the immediate “declaration of a housing emergency” in the city.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.