Earlier this year I gave a talk on the Fintan Lalor Pipe Band for a conference entitled Music in Ireland: 1916 and Beyond. The FLPB would come to be seen as the ‘band of the Irish Citizen Army’, and were in their own right an important part of Jim Larkin’s cultural vision. This is an edited version of that talk.

Studies of the Irish Citizen Army, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and other working class organisations in the revolutionary period have tended to focus on their political histories – examining events and themes such as the Lockout of 1913, the Easter Rising and the political ideology of leaders like Larkin and Connolly. There is still, I would maintain, much work to be done on the culture of the radical trade union movement of revolutionary Ireland.

What James Larkin attempted to do in Dublin from the time of his arrival in the city in 1908 amounted to more than political revolution – there was an enormous social dimension to his project. Emmet O’Connor, Larkin’s most outstanding biographer to date, contends that Liberty Hall was the centre of a working class “counter culture.” It had a theatre, a printing press, a workers co-operative shop, food facilities and more besides. To the movement of Larkin and Connolly, culture formed an important component – and perhaps no aspect of it was more important than the Fintan Lalor Pipe Band, who would lead their movement through the streets.

Jim Larkin’s arrival in Ireland:

Jim Larkin, born in Toxteth in Liverpool to Irish parents in 1867, remains the single most important figure – and one of the most divisive figures – in the history of Irish trade unionism and labor politics .He arrived in Ireland in 1907 as a trade union organiser with the National Union of Dock Labourers, sent to organise on the docks of Belfast, where he succeeded in doing the unimaginable and defying the sectarian divisions there, something well-documented in John Gray’s study City in Revolt. Larkin was renowned for his deployment of the sympathetic strike tactic – believing that an injury to one was an injury to all – undoubtedly one contributing factor that led to his sacking by the NUDL and his decision to establish his own union, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, which he based in Dublin. This was a revolutionary union committed to the overthrow of capitalism, and modeled on the politics of syndicalism – that is a belief that workers’ could transform society through unified industrial action. A journalist from The Times in Britain wrote of ‘Larkinism’ in 1911 that:

For the present it is enough to say that the object of Mr.Larkin’s Union is to syndicalise Irish Labour, skilled and unskilled, in a single organisation, the whole forces of which can be brought to bear on any single dispute in the Irish industrial world.

Summing up ‘Larkinism’ himself, Jim Larkin stated:

“The employers know no sectionalism. The employers give us the title of the ‘working class’. Let us be proud of the term. Let us have, then, the one union, and not, as now, 1,100 separate unions, each acting upon its own. When one union is locked out or on strike, other unions or sections are either apathetic or scab on those in dispute. A stop must be put to this organised blacklegging.”

The rise of Liberty Hall:

Larkin based his new union in what he called Liberty Hall, a former hotel which had fallen into rack and run. This premises offered everything an emerging movement could need; as Emmet O’Connor has noted, it “offered rooms for band practice, Irish language classes, a choir and a drama society.” Liberty Hall would prove a tremendous resource to the labour movement, providing the location for a printing press for example, and as Christopher Murray has noted in his biography of Sean O’Casey its former life as a hotel proved invaluable on occasion, not least in 1913 when “the old kitchens were still usable in the basement.”

Much has been written of Larkinism in labour dispute – little has been written of the culture that surrounded Liberty Hall. Indeed, the Manchester Guardian was so moved by Larkin’s project, that they proclaimed “no Labour headquarters in Europe has contributed so valuably to the brightening of the lives of the hard-driven workers around it…it is a hive of social life.” For Larkin, there was an enormous emphasis on the self-respect and dignity of the working class, and in their visible orgnaisation and solidarity.James Plunkett, in an essay of remembrance, recalled that:

Torchlight processions and bands, songs and slogans and the thunder of speeches from the windows of Liberty Hall, these were his weapons, and he calculated than a man with an empty belly would stand the pain of it better if you could succeed in filling his head full of poetry. Those who previously had nothing with which to fill out the commonplace of drab days could now march in processions, wave torches, yell out songs…It was Larkin’s triumph to inject enough of it into a starving class to lift them off their knees and lead them out of the pit.

An often overlooked but hugely important part of Larkin’s personality – and something James Connolly shared – was his commitment to a teetotal lifestyle. The public house was often denounced in the pages of his newspaper The Irish Worker, he denounced the popular politician Alfie Byrne as Alfie Bung for owning a pub, and even led the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union onto a temperance parade in 1911. As much as anything else then, Liberty Hall was designed to get men out of the pubs and to keep them out of the pubs.

This in the context in which the Fintan Lalor Pipe Band was born – the emergence of a ‘counter culture’ for the working classes, which brought learning, creativity and community into the doors of a crumbling old hotel, and invented Liberty Hall. Later, one newspaper would describe it as “the brain of every riot and disturbance” the city witnessed.

Continue Reading »

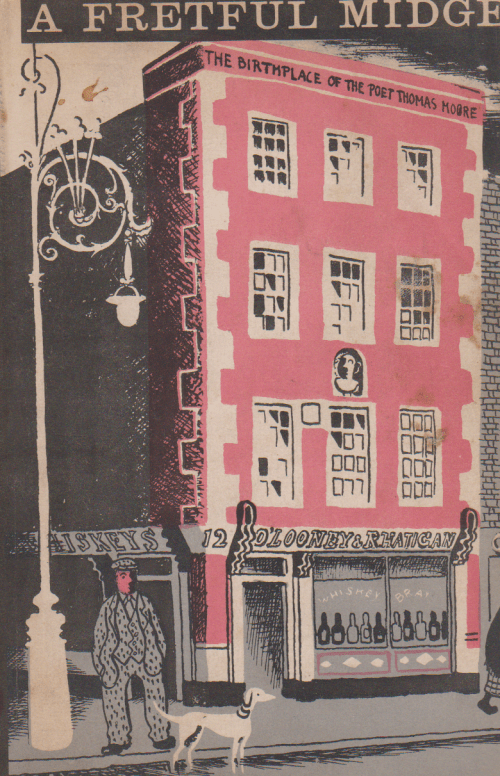

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.