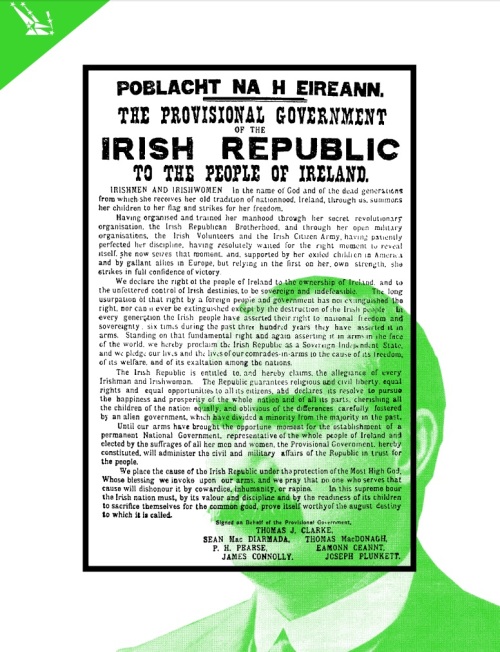

In the folklore of the Easter Rising, the Helga is said to have brought about the destruction of the city, raining incendiary shells down on the rebels from her fine vantage point on the River Liffey. In reality, there were no incendiary shells (they hadn’t been utilised anywhere by April 1916), and the Helga fired only forty shells during the course of the rebellion. Still, when coupled with the use of eighteen-pounder guns on the streets, she no doubt had an impact. The majority of her shells were fired at Liberty Hall, which unbeknownst to the Helga was empty.

By empty, I mean ‘almost empty’; the caretaker Peter Ennis was on the premises, and thankfully escaped with his life. Frank Robbins, ICA member and author of a memoir of the revolutionary period, remembered that “Ennis told me that when the first shell hit the building he thought that the whole place was collapsing around him.”

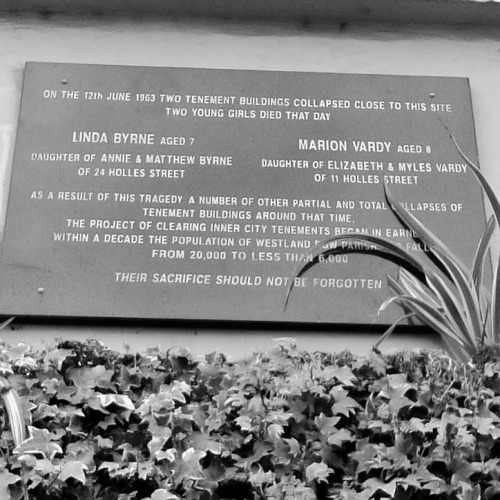

Much of the damage done to the centre of Dublin over Easter Week was the end product of intense fires, something that was well-detailed by Captain Thomas P. Purcell of the Dublin Fire Brigade. His map, showing the destruction of the O’Connell Street area of the city, was included in a CHTM post on the looters of 1916 before. Looters burning buildings, such as Lawrence’s toy shop, were undoubtedly a factor in the carnage, but so too was the use of heavy artillery on the streets.

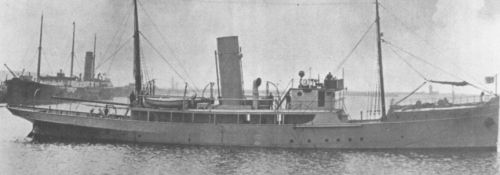

The Helga in happier times, photographed in 1908.

The Helga was not only utilised against the rebel forces in Dublin in 1916, she was herself a product of the city. Built on the docks of the Liffey for the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction in 1908, she was rushed into military service with the outbreak of the First World War. As Lar Joye of the National Museum has detailed, “like much of the British government’s response to the 1916 Rising, the Helga was rushed into service to make up for the British Army’s lack of artillery.” The presence of the Helga on the River Liffey was commented on by many Volunteers in their statements to the Bureau of Military History, and no doubt the sound of her firing shells was terrifying. Domhnall Ó Buachalla remembered being engaged in a firefight from the Dublin Bread Company on O’Connell Street, one of the architectural losses of the Rising, and that:

I engaged some soldiers on the roof of Trinity College and, while I drew back from the loophole in the barricaded window from which firing, a bullet came through and grazed my hair. I could see Liberty Hall from the window and observed the effect of the shelling by the British war vessel – the Helga – and saw some of the walls crumble and fall.

It’s possible Ó Buachalla was referring to the building beside the trade union hall, Northumberland House, which was destroyed by the Helga‘s shelling. Liberty Hall itself, despite damage to the buildings exterior, emerged from the Easter Rising relatively fortunately. The project to repair the building was overseen by Commandant James O’Neill of the Irish Citizen Army, who worked in the construction industry. By the first anniversary of the insurrection, repair work was still on-going on the premises. An excellent recent article from Michael Barry examines the impact, or lack thereof in places, of the shelling of Liberty Hall from the other side of the Loopline Bridge, where the Helga was positioned in front of the Custom House.

Two years after the Rising, the Helga was used as a rescue ship when the RMS Leinster was torpedoed by a German U-Boat. Peculiarly, given her history of service at Easter Week, she was taken over by the new Free State post-independence as a patrol vessel, and renamed the Muirchú, becoming one of the first ships of a new Irish Navy. She was utilised against republican forces in Munster during the Civil War, when the tactic of landing men by sea provided the Free State with a way of circumventing republican ambush points.

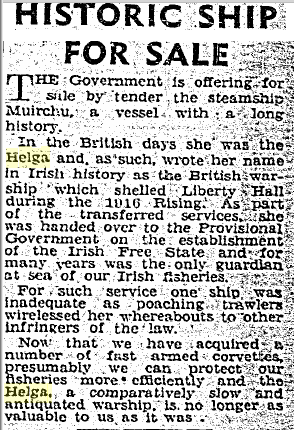

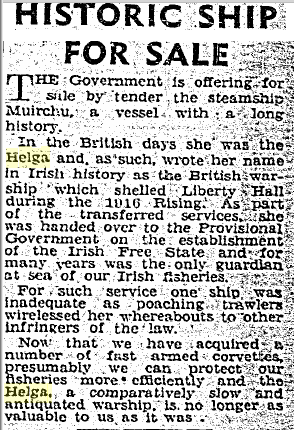

In 1947, the Helga was making headlines again. It was reported that the Government were offering her for sale by tender, as:

…now that we have acquired a number of fast armed corvettes, presumably we can protect our fisheries more efficiently and the Helga, a comparatively slow and antiqued warship, is no longer as valuable to us as it was.

Sunday Independent, 16 March 1947.

The Hammond Lane Metal Company on Pearse Street purchased the ship, and the Irish Press reported in May 47 that she was to be taken to Dublin from Cork “to be broken up for scrap at the purchasers’ Ringsend ship-breaking yard.”

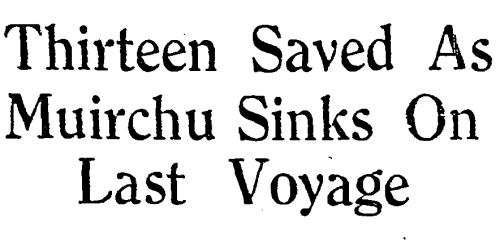

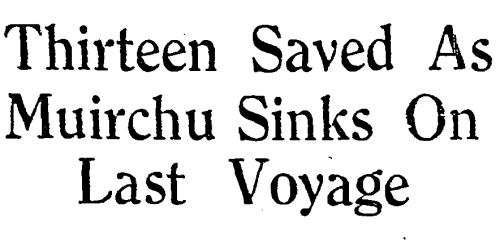

She never made it to Ringsend. It was reported on 9 May that the ship sank “yesterday morning some eight miles south of the Coningbeg Lightship off the Wexford coast. The crew of ten and three passengers were taken off by a Welsh fishing trawler and later landed at Milford Haven in Wales.”

Newspaper coverage of her final voyage.

Just what went wrong on her final voyage? The Irish Press reported that “It is believed that the vibration of her engines, following a long lie-up at Hawlbowline Dockyard, Cork, until she was bought by the Hammond Lane Foundry recently for breaking up, dislodged her plates and she sprang a leak.” One of those on the ship was Brian Inglis, a journalist with The Irish Times. He would detail the panic in getting off the ship in the pages of the newspaper, remembering that the oars were “old and rotten and one was snapped in two”

Captain David Thompson, who had been on-board the Helga in 1916, was asked for comment by a newspaper when news of the ship sinking became known. He was reluctant to talk about its role in 1916, beyond saying that “it was a thing that should never have been done, especially to call on a local ship and crew.”

While her story began in Dublin in 1908, and she will forever be associated with the Rising in the capital, it ends off the coast of Wexford. She was, to quote one newspaper, spared the ignominy of the breaker’s yard in her old age.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.