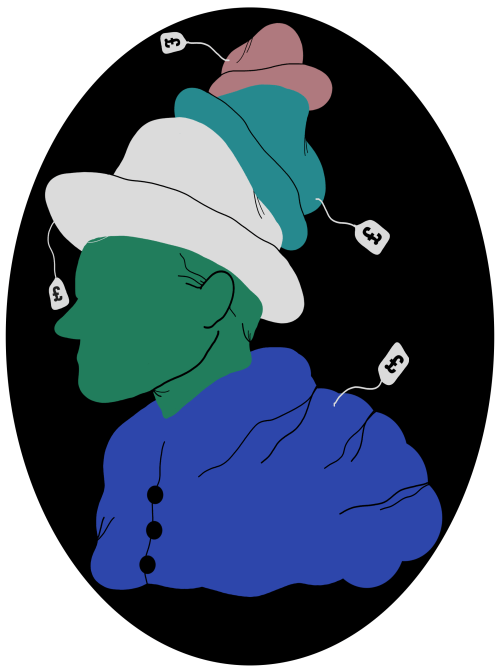

It seems not even sports annuals, political memoirs or celebrity cookbooks can match the Easter Rising industry this year.

Dozens upon dozens of books have been published in recent months on the 1916 insurrection, with the floodgates well and truly opened in recent weeks. With all of this, you could easily forget that some of these books are actually quite good! Many of the books below are labours of love that have long been in the pipeline, and I hope this list comes in handy for anyone who has to brave Hodges Figgis, Chapters or Easons in the days ahead. My own contribution is a biography of John MacBride, recently released as part of the on-going 16 Lives series.

Jimmy Wren: The GPO Garrison Easter Week 1916: A Biographical Dictionary (Geography Publications)

It is always the way, that for all the academic conferences and edited collections, that the finest works will be labours of love that come from left-field. Jimmy Wren’s study is a triumph of local studies that has to be seen to be believed in terms of ambition and scale. Jimmy Wren’s father, James, and his father’s first cousins, Paddy and Tommy, were members of the GPO Garrison during Easter Week. The problem, of course, is that depending who one asks, it seems half of Ireland was within the four walls of Francis Johnstone’s General Post Office.

In this book, Jimmy has provided brief biographical sketches of every member of the GPO Garrison in 1916, from Mary Afrien (Cumann na mBan, 1875-1949) to Nancy Wyse Power (Cumann na mBan, 1889-1963). A talented artist, he also provides wonderful pencil sketches of many of the men, women and children in the GPO Garrison. For 1916 nuts, the appendix list alone is worth seeing. One appendix lists the “political involvement of members of the GPO Garrison post-1916”, while another is bound to cause a row or two: “People whose obituaries state they were in the GPO Garrison but do not appear in official sources.” My copy is already well-thumbed, and this is the kind of book that you might not read in the traditional sense from cover to cover, but rather will constantly dip into as a reference guide.

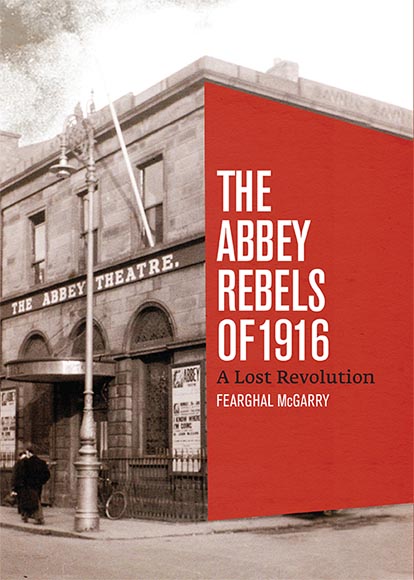

Fearghal McGarry: The Abbey Rebels of 1916: A Lost Revolution. (Gill & MacMillan)

I have long been an admirer of McGarry’s work on 1930s left-wing and right-wing political movements in Irish society. He is an authority on the Spanish Civil War in an Irish context, and has also produced strong biographies of Eoin O’Duffy and Frank Ryan. Recent years have seen him take a keen interest in the earlier revolutionary period, and his book The Rising was one of the first to draw on the Witness Statements of the Bureau of Military History, capturing the madness of the week from firsthand accounts, right down to the looting of Noblett’s sweetshop.

This study sees McGarry looking at the Abbey Theatre and its role in the Easter Rising, looking at the diverse figures associated with the institution who took part in the drama off-stage. He notes that it was inspired by the Abbey’s commemorative plaque in the foyer of the Theatre, which includes a line from Cathleen ni Houlihan; “It is a hard service they take that help me.” For the most part, the names upon it “were working class Dubliners, followers rather than leaders, whose role on the historical stage seemed to come to an end after Easter Week.” Here, a spotlight is shown on these lives. Seán Connolly, the talented actor who was to be on stage in the theatre that week, instead found his place in history as the first rebel to die in the scrap, shot on the roof of City Hall. Arthur Shields (brother of Barry Fitzgerald) fought in the Sackville Street area, and later became a respected screen actor, even bizarrely appearing alongside John Loder in How Green Was My Valley? in the early 1940s. Why was that bizarre? Well, John Loder was none other than John Lowe, son of General Lowe to whom P.H Pearse surrendered at the end of the Rising. John can be seen in the famous image of the surrender, standing alongside his father.

McGarry’s book is beautifully illustrated, drawing from the archives of the Abbey Theatre themselves, and the collaboration between historian and institution is what makes this book work so well. In his concluding remarks, McGarry correctly notes of the year ahead of us that “the centenary will see the Easter Rising reinterpreted in ways that are relevant to the present. Rather than simply re-enacting the past, the most successful commemoration, as the revolutionary generation demonstrated through their appropriation of 1798, draws on its energies to imagine alternative futures.”

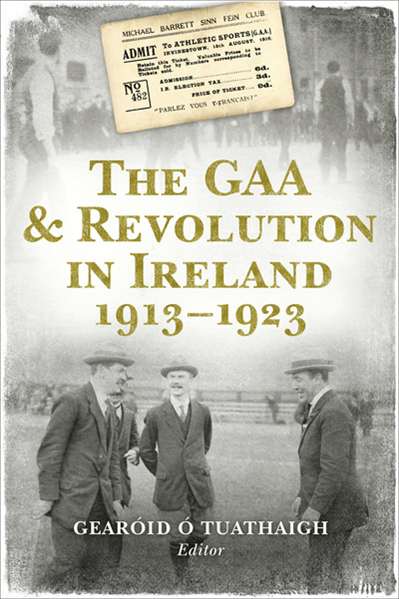

Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh (Ed.): The GAA & Revolution in Ireland 1913-1923 (Collins Press)

This book succeeds in bringing together some of the most important figures in the writing of Irish sports history, including Paul Rouse (whose recent all-encompassing history of sport in Ireland is a fine achievement), Richard McElligot (who has looked at the intersections between Kerry GAA and Kerry IRA in great detail) and Cormac Moore, author of The GAA vs. Douglas Hyde, which examined the fallout following the Irish President daring to visit Dalymount Park in 1938. Its editor, Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, is one of the most respected historians in Ireland today, and a man who established himself as an important voice in Irish academia with the publication of Ireland before the Famine in the early 1970s. Despite the strong academic credentials of many of the names in this book, it manages to be both scholarly and accessible, and will appeal both to historians and the passionate GAA community.

Ross O’Carroll’s chapter, The GAA and the First World War, 1914-18, will certainly shatter some illusions, showing how the organisation supported the war effort in parts of Ireland, and noting how some of the most promising players of the age were lost on foreign battlefields. We read of Lance Sergeant William Manning, who played for Antrim in the 1912 All Ireland Football Final, and who died in the uniform of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in France in May 1918. In The Gaelic Athlete, it was written that “the European crisis has been responsible for many of our most prominent teams ‘going weak’, with the Saint Peter’s club having lost ‘no less than nine of their best players.'” O’Caroll quotes a source from the early 1930s that bemoaned the fact that while most of the GAA stood firm to its “old ideals and to the principles of its founders…it is sad to relate that a few one-time prominent members of the GAA turned recruiting sergeants for England…” From reading this chapter however, it is clear that like many other aspects of Irish life, the GAA was affected by battles far from home, as well as battles here.

The book also throws interesting light on how the authorities viewed the GAA in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, while trying to make sense of what had taken place. The Royal Commission into the causes of the rebellion, McElligot tells us, believed that the Irish Volunteers had “practically full control over the Association”, while one former GAA Secretary basked in the inclusion of the GAA’s name in the inquiry, as it would “be most uncomplimentary to the Association if it were omitted.”

Conor McNamara – The Easter Rebellion 1916: A New Illustrated History (Collins Press)

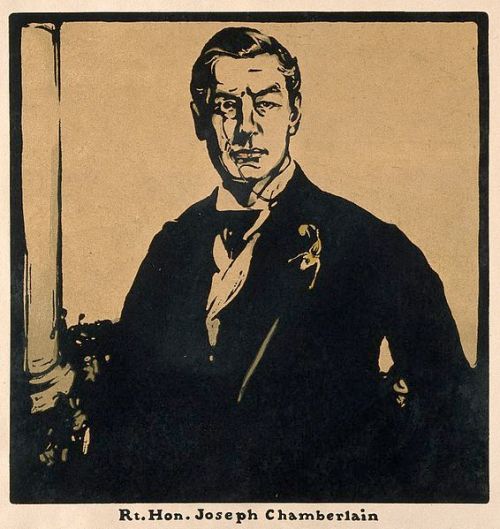

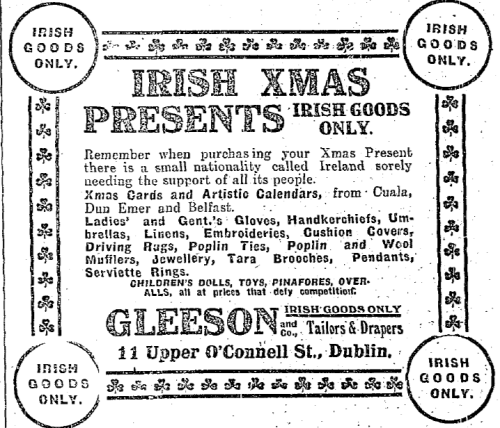

Conor McNamara is currently the ‘1916 Scholar in Residence’ at NUI Galway, and readers may be interested in the recording of a recent History Ireland Hedge School on the theme of the 1916 Rising in Galway and the West of Ireland, to which McNamara contributed. We can sometimes forget that the Rising was not envisioned by its planners as an almost entirely Dublin-centric event, and this new illustrated history is particularly strong on the background to the Rising, both in terms of the key protagonists and the planning of the event. Any true history of the 1916 Rising can’t begin on the 24th April 1916 – The Gaelic Revival, the rise of militant trade unionism, the re-emergence of the Irish Republican Brotherhood as a serious political force and many more factors must be examined, and McNamara does that well here. He draws on some unusual sources, including a great republican cartoon from c.1915, showing John Redmond dressed in the attire of Charlie Chaplin, with the caption “The Irish political Charlie Chaplin, with apologies to the real Charlie.”

Great credit has to go to Collins Press for getting this book totally right in terms of production. Many illustrated histories have suffered to cost-cutting measures with regards size and quality of images, but here images are reproduced in their full glory, including a fine series of World War One recruitment posters given a full page each. “Who can beat this plucky four?” one poster asks, showing soldiers from the four nations of Great Britain with their respective national flags attached to their rifles. Beautiful postcards from the collections of the National Library of Ireland appear too, including one entitled “Across the gulf of time”, showing a Redmonite ‘National Volunteer’ shaking the hand of a Volunteer of the 1780s. This is a treasure trove of great visual primary sources.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.