The way we drink in Dublin has been changing over the last few years; I can’t say evolving, so much as there has been a restoration of natural order. Craft beers vie for counter space alongside Diageo products and pubs like the Black Sheep, Against the Grain and The Beerhouse have sprung up to back up the Porterhouse in breaking the Guinness monopoly. Most importantly, our brewers are starting to brew again, with Five Lamps Brewery and JW Sweetman’s to name but two.

I say ‘again’ as while for decades Guinness and later their parent company Diageo would fully monopolise brewing in Dublin, ours was once an industry that could “present an unrivalled record to the world” (Irish Independent, 05/06/1908) and this city’s brewing was said, as far back as the 17th century to be “the very marrow bone of the commonwealth of Dublin.” (http://simtec.us/dublinbrewing/history.html) The excise list for 1768 showed returns for forty three brewers in the city, with many of these large operations employing dozens of workers.

Throughout the 1800’s, with the rise of Guinness’, Dublin’s breweries either amalgamated or closed so by 1850, there were twenty breweries left, by the 1870’s, there were ten left, and by 1920, there were just four breweries including Guinness’ operating in Dublin. One of the largest breweries during this time was Watkins’ Brewery, originally founded as the Ardee Street Brewery, and later known by the title of Watkins, Jameson, Pim & Co., Ltd.

Advertisement for Watkins’ Brewers. From the Aonach an Garda programme,1926.

A date for the foundation of the brewery is hard to ascertain, but the Irish Times, in an article on Dublin brewers (21/01/1932) reported that Watkins’ “of Ardee Street Brewery hold the record of having paid the highest excise duty of any Dublin brewer in 1766” so its going at least that long, with the excise list naming Alderman James Taylor as the owner. By the 1820’s, the brewery at Ardee Street was the third largest in Dublin, with an output of 300 barrels per week. It was bettered only by Guinness’ with 600 barrels per week and Michael Sweetman’s with 450 barrels per week.

By 1865 the brewery was exporting over 14, 000 hogsheads or approximately six million imperial pints of stout. (Findlaters: The Story of a Dublin Merchant Family 1774-2001, chapter 4.) The brewery was dissected by Cork Street, with the brewing house and offices on its south side, and 87 dwellings for their workers on the north side, some of which exist today, as can be seen in the image below. The houses were built at at outlay of £14, 460, with rents “from 2/6 to 6/-.” (Irish Independent, Sept. 12th, 1913.)

Watkins’ Buildings, and all that remains of the brewery.

The Freemans’ Journal, (12/02/1904) spoke of rumours circulating Dublin of an amalgamation of two of its more prosperous breweries, namely Watkins’ and Jameson, Pim and Co., who would move from their premises between Anne Street and Beresford Street to make way for another Jameson: John Jameson and Son, the whiskey distillers. The article also reported that the Watkins’ family had “long since disappeared, and the business now carried on by Mr. Alfred S. Darley.”

The brewery saw action (although not much) during the 1916 rising, when it was occupied by Con Colbert (a teetotaller) and a garrison of 20 men- an outpost under the direct command of Eamonn Ceannt in the South Dublin Union. The outpost was ineffective, and the volunteers eventually joined up with the Marrowbone Lane distillery garrison. It was also tragically caught up in the events of the “Battle of Dublin,” a week of clashes in Dublin from 28th June to 5th July 1922, at the start of the Civil War that saw over sixty people killed. A cooper by the name of James Clarke who worked in the brewery was shot near Gardiner’s Row on the 6th July whilst walking a friend home. He took a bullet straight to the face and died half an hour after admission to Jervis Street Hospital.

O’Connell’s Dublin Ale

Towards the end of the twenties, Watkins’ Jameson, Pim and Co. acquired Darcy’s Brewery and it’s trademarks, including O’Connell’s Dublin Ale, which we’ve mentioned briefly on here before. The Findlaters book acknowledges the takeover of Darcy’s brewery, and also mentions that the company owned several Dublin pubs, “which it called Taps.” In March 1937, the financial paragraph of the Irish Times announced that the firm was in voluntary liquidation. The article shows that at the time, the brewery still employed over one hundred men, and blamed rising excise and falling exports for their downturn.The Findlaters book above also says that while the company outlasted many of it’s competitors, it closed down in 1939.

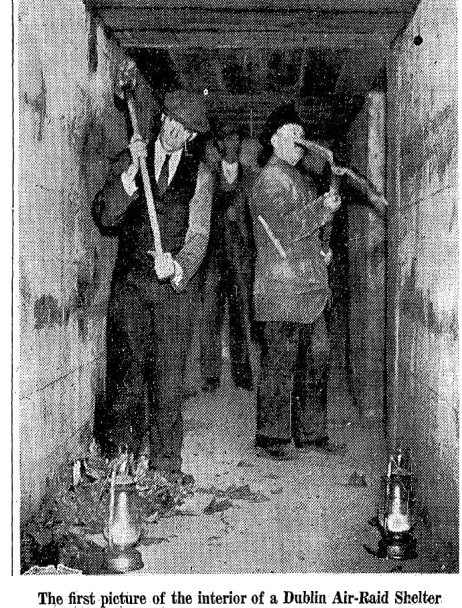

We took a look at Dublin’s air raid shelters recently, and in 1943, the brewery was subject to a high court wrangle with a High Court judge quashing a warrant issued by a district justice who, under the “Air Raid Precautions Act, 1939” demanded that the Dublin Corporation be allowed enter the brewery, by force if necessary, to build a shelter in its basement. The demand wasn’t met. After this, as the excellent Wide and Convenient Streets concur, things get a little bit hazy regarding the brewery. In September 1951, there was a large fire at the site, and by 1954, advertisements pop up in various papers offering factory premises to let. With a history spanning three centuries, the brewery seems to have gone “quietly into that good night” along with the rest of Dublin’s breweries, which we hope to cover in the near future.

* Company records sites suggest there was a “Watkins, Jameson, Pim & Co. (1976) Limited” set up on Wed the 28th of Apr 1976 and is still in existence at 10 Ardee Street.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.