All you punks and all you teds

National Front and Natti dreds

Mods, rockers, hippies and skinheads

Keep on fighting ’till you’re dead

Talking to Come Here To Me!, Garry O’Neill (editor of Dublin street fashion photography book Where Were You?) summed up the violent mood that he felt growing up in Dublin in the mid-1970s:

To me, at that time, Dublin seemed a violent place. It was a social problem that existed before the punk explosion and the skinhead/mod revivals of the late 70s. Growing up in the city centre in the mid 70s there seemed to be a very tribal and territorial element to the violence that occurred. The city’s cold and grey complexion compounded the fear of walking through certain areas where you might be visiting a new girlfriend or friend, meaning that unless you took a bus, you had to safely navigate a way out of said area and through one or two more before finally reaching your home patch, thus avoiding some of the bootboy gangs and odd individuals that seemed to exist purely to take exception to the fact that “You’re not from around here” before meeting out a well placed box or boot to send you on your way.

In regard to its Punk and local live music scene, artist Garret Phelan has signalled out Dublin as being different to other cities in the South of Ireland:

It was bonkers (in Dublin). I would be shitting my pants going to some of these gigs. I was talking to a mate of mine who grew up very much within the music scene in Cork, and he never experienced the fear factor that you would experience in going to gigs here. Going to gigs here, you took your life into your hands.

At Ireland’s first punk festival (25 June 1977) in the canteen on UCD’s Belfield campus, a young fan from Cabra was stabbed twice after a short fracas broke during the gig involving eight or nine people. He later died of his injuries in a hospital in the early hours of the morning. Gavin Friday, lead singer with The Virgin Prunes, believes that it could have been ‘the first murder at a rock gig in the British Isles.

Garry O’Neill, whose eldest brother was at the gig, recalled:

It was the first time I’d heard of violence at a gig. The only other incident I knew about was the Bay City Rollers gig at the Star Cinema in Crumlin in 1974. When into the gig went gangs of girls from all over the city, leaving their gangs of boyfriends outside to run amok amongst themselves.

As the punk scene in Dublin grew in popularity and began to attract fans from all over the city, incidents of faction fighting and recreational violence grew. Some noticeable violence occurred at the following gigs:

– 12 November 1977: The Stranglers (who didn’t show up), The Radio Stars and The Vipers in the Tivoli Theatre, Francis Street. Original guitarist for The Vipers Ray Ellis recalled:

There was a riot going on when we arrived – seats being ripped up (and) general mayhem. We got into it and the place went wild. While I was playing, a guy in the crowd pointed at my shoe and my lace was open … I gave him a nod and put my foot over to have him tie my lace. He grabbed my foot (and) started to pull me off the stage. The bouncers at the side curtain saw me disappearing but could not see why and thought … it was part of the act till they saw my face so they grabbed my head. There was a tug of was between them and the crowd. Happily they won and I was kept on stage and finished the set.

Ticket stub for The Stranglers gig who didn’t turn up. Credit – U2earlydayz.com

– 12 October 1978: The Virgin Prunes were bottled off stage while supporting The Clash at the Top Hat, Dun Laoghaire. It was their second gig. Gavin Friday remembers:

We came on (with) Guggi wearing a tiny skirt and I had a plastic suit made out of raincoats, no jocks underneath, and pair of Docs. We’d only played two little gigs before that. Steve Averill from The Radiators From Space played synthesizer with us. The crowd just went apeshit. They thought Guggi was a chick. The adrenaline of all these people pogoing kicked in and I started jumping around, the next thing this plastic suit that me ma had made me split completely. I was standing there totally bollock naked, except for a pair of Doc Martins. I turned around and Guggi’s skirt had come off and you could see that he was a bloke. All hell broke loose, there were bottles flying, they were setting the curtains on fire. We were reefed off the stage by The Clash’s tour manager and fucked out the door. We had no money and had to walk with all out gear, back from Dun Laoghaire to Ballymun.

– 20 October 1978: Violence again at The Top Hat with The Jam.

– May 1979: Black Catholics trouble at a U2 gig (supporting Patrick Fitzgerald) in the Project Arts Centre. The late great Bill Graham of Hot Press wrote at the time:

Last weekend at the Project, U2, who were supporting Patrick Fitzgerald were targets of an unprovoked assault. As our man on the move Ross Fitzsimons reports a group arrived down & began taunting the band but the verbal displeasure escalated to direct and seemingly drunken action as critics jumped on stage, threw cider about & in one instance kicked U2 bassist Adam Clayton. After two numbers, the band quit the stage & the situation became so unruly that two Gardai had to called to escort the disruptors from the premises. That was Friday night but the following evening, the vendetta continued. One troublesome patron was speedily ejected by U2 manager Paul McGuinness but after McGuinness returned to the auditorium, a bruising skirmish ensued in the foyer & outside.

Black Catholics and friends. Advance Records by Stephen’s Green. Credit – Patrick Brockleband via Eamon Delaney’s blog

– 17 November 1979: Trouble at the Squeeze gig in Belfield, UCD.

– 1979: Brawls at a fundraiser gig for the UCD Student Union with DC Nein and The Threat at the Student Bar in Belfield. Maurice Foley, guitarist and the lead vocalist of The Threat, remembers:

I remember one time we played with DC Nien in Belfield… and there was a bit of trouble there… Whatever it was, someone from Hot Press came out to ask me about something… we had this old van that kept running out of water and all the lads were waiting to get in the back after the gig and then this car came in really close beside us and it nearly knocked a few of the lads over, they had to jump out of the way… and it pulled up outside the Students Union Bar… then they got out and they were all loud, they’d had a few drinks and the car could have been stolen ‘cos they were driving all over the grass and stuff… so our lads thought they’d go down and have a word with them in the car… so they ended up smashing all the windows in the car… some chains came out and that… so they drove off and went into the students bar and the students all came out with them and they started attacking… there wasn’t a large crowd of us either… so everybody crowded into the back of the van and we started the van to get it going, but it wouldn’t start… they all came close and started firing rocks, and the lads had to get out to chase them off again.

– December 1979: Fighting at The Members gig supported by Stiff Little Fingers in the Olympic Ballroom, Pleasant Street.

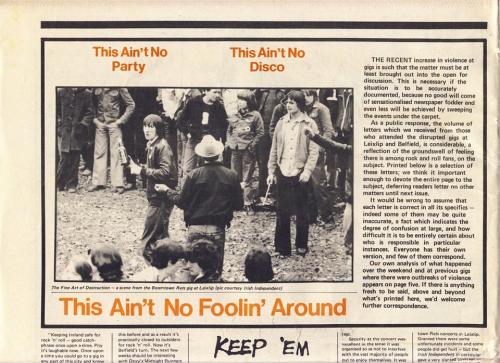

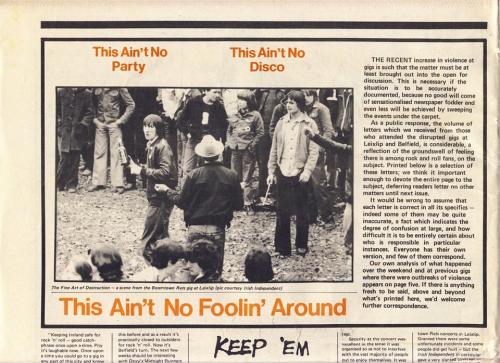

– 2 March 1980: 49 people were injured in the crowd trouble at The Boomtown Rats and The Atrix concert at Leixlip Castle.

The Boomtown Rats at Leixlip Castle. Hot Press – March 1980. Credit – Where Were You? Facebook page

– May 1980: Aggro at The Rezillos, The Tourists and The Epidemix gig in Liberty Hall.

– 27 July 1980: Bottle throwing at The Police gig at Leixlip Castle.

– 6 October 1980: A hammer attack at a 4″ Be 2″‘s gig in Trinity College. The band featured John Lydon’s younger brother Jimmy. Lydon (aka Johnny Rotten) was arrested that evening for assault after a melee in the Horse & Tram pub, Eden Quay, Dublin, he was sentenced to three months in jail for disorderly conduct but was eventually acquitted on appeal.

– 8 October 1980: Four people were stabbed after The Ramones gig at Grand Cinema, Quarry Road, Cabra.

– 15 January 1981: Hectic scenes at The Specials and The Beat concert at The Stardust, Artane. Gang violence between the “Edenmore Dragons” from Raheny and the “Coolock Boot Boys” from Coolock marred the legendary gig. Edna on Brand New Retro described it as a ‘ bloodbath of a gig’ while Festeron on the TheSpecials2.com forum recalled ‘The gig .. was ruined by fighting between 2 rival Dublin gangs … They used the dance floor as a battleground that night despite Terrys best efforts to make peace. “‘

– 1981: The Outcasts gig in McGonagles saw the bar being raided by punters and fighting occurring inside and outside the gig.

Continue Reading »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.