This month marks the centenary of Cumann na mBán being founded in Dublin, and there has been much talk about the role of women in Irish political history. While Cumann na mBán was a nationalist organisation focused on providing practical support to the male Irish Volunteers, many other women were also active in politics a century ago, ranging from trade unionism to suffrage campaigns seeking the vote. This brief post looks at some examples of militant opposition to suffragists on the streets of the capital, and while it’s not a subject I’ve a great familiarity with I found all of these little stories interesting and worth sharing.

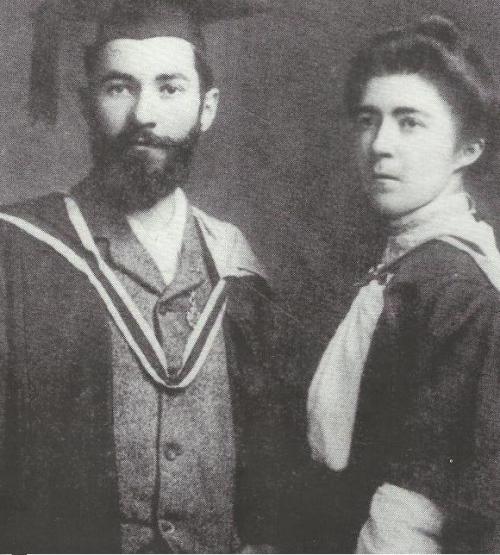

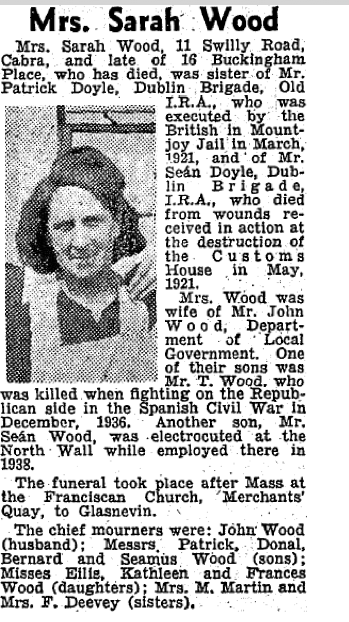

Francis Sheehy Skeffington, who refereed to the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians as the “Anicent Order of Hooligans”.

The ‘Ancient Order of Hooligans’ in the Phoenix Park, August 1912.

In early August 1912, a huge crowd assembled in the Phoenix Park to hear a number of male and female speakers discuss the need for votes for Irish women. The Irish Times commented that “uproar and considerable interruption were a leading feature” of the event, with the paper noting that “several attempts were made to rush the platform”.

Vigorous hissing, booing and groaning greeted the speakers at almost every stage of the proceedings, which were opened by the police taking the precaution of forming a wide space between the mob and the position taken up by the suffragists.

One of those to speak was Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a prominent figure in Dublin at the time, “who was accorded a very hostile reception, which he appeared to regard with considerable satisfaction.” Skeffington caused pandemonium by addressing the crowd as “Ladies, Gentlemen and members of the Ancient Order of Hooligans”, a reference to the conservative Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians. Despite the fact missiles were thrown at the stage on this particular occasion, the speakers succeeded in leaving the park in safety, vowing to return at a later date.

The Phoenix Park was a regular spot for political demonstrations at this period in Irish history. Only weeks after the above rally was disrupted, another pro-suffrage rally in the park encountered similar hostility. On that occasion, prominent Dublin Jew Joe Edelstein spoke of his belief in the right of women to vote, asking the crowd “whether they were the people who gave to Ireland Wolfe Tone, Robert Emmet, Michael Davitt etc, who were now going to condemn their own sisters, their mothers and their daughters.” Edelstein’s appeals to the crowd, much like Skeffington’s, went down like a lead balloon. Edelstein appears in the newspapers the following month at a suffrage meeting once more, though on that occasion openly hostile to the movement! At a meeting in September 1912, Edelstein drew loud boos from women by asking if “the Irish people should subjugate the great important question of Home Rule to a petty movement like theirs.”

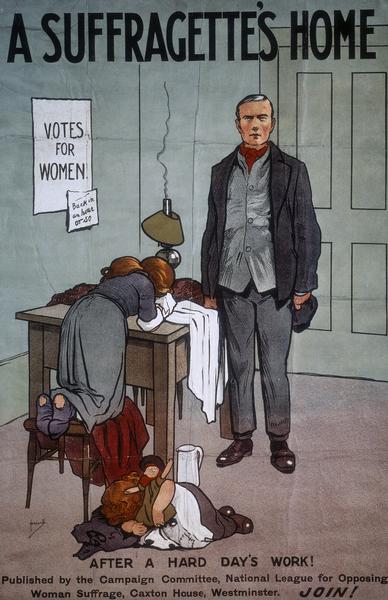

The Women’s Anti-Suffrage League.

Not all women who involved themselves in suffrage politics were seeking the vote. Some were quite opposed to the very idea. One such organisation was the Women’s Anti-Suffrage League, who attracted considerable attention in the media. Detailed reports of the Annual General Meeting of this body appeared in the Irish media in March 1912, where the following motion was carried:

That we, as women, appeal to the women of Ireland to express their profound disapproval of the late exhibition of lawlessness by militant suffragists, and to condemn such action as fatally injurious to the best interests of their sex.

One woman noted that it was with feelings of “indignation, mortification and shame” that many of them had read of the actions of militant female activists. The first references to this body being established in Dublin appeared in the media in February 1909, and the League seem to have brought a number of figures from the anti-suffrage movement in Britain to Dublin on public speaking engagements. Elizabeth Crawford has noted that in the years prior to the First World War the chairperson of the Anti Suffrage League in Dublin was a Mrs. Bernard, who was also the wife of the Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Chased down the street and onto a tram, August 1912.

On 8 August 1912, the following brief report appeared in The Irish Times:

When passing through Henry Street yesterday afternoon…a young woman, whom the crowd regarded as a suffragist was attacked, and a noisy scene followed. She was pursued in the direction of Nelson Pillar, where the police intervened, and saved her from the mob by getting her into a tramcar which was going in the direction of Dalkey. A good deal of excitement was caused, and as the tramcar moved off, a large section of the crowd gave chase…giving vent to their feelings as they ran along.

Trinity College Dublin students goading suffragists, 1914.

Previously on the blog, we’ve looked at the phenomenon of Trinity Monday in the early twentieth century, a day when new Scholars were announced on-campus and Trinity students tended to run amuck around Dublin. Shortly after midday on Trinity Monday in 1914,there were unexpected visitors at the offices of the Women’s Social and Political Union on Clare Street. The Irish Independent reported that “a large number of students arrived here” and that “a number of them bundled papers and banners together and threw them out of the window to a cheering crowd outside.” Not content with this, a political flag belonging to the movement was stolen, which was later carried triumphantly from the building. The students made for the Mansion House, and rushed the building as a delivery was taking place. The Irish Times reported that:

On a landing they found the municipal flag, which owing to the absence of the Lord Mayor from the city was not hoisted on the pole on the house-top. The students tore up the flag, and hoisted the ‘Suffragette’ flag upon the flagpole. For an hour this floated over the Mansion House.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.