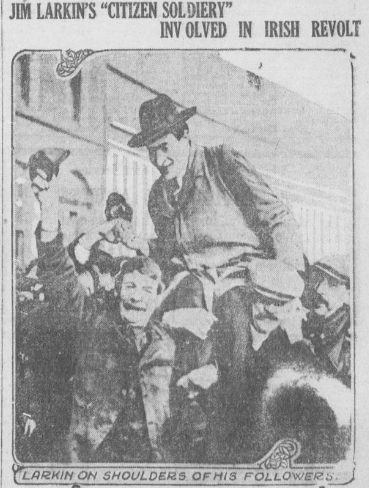

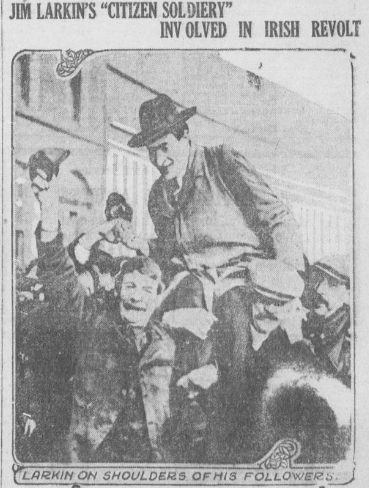

The Daily Capital (Oregon) reports on the involvement of followers of Jim Larkin in 1916 rebellion.

It’s almost a century since the Easter Rising broke out on the streets of the capital. Today, news travels quickly throughout the world with an international press and ever evolving technology, but how was the 1916 reported internationally at the time? The U.S Library of Congress website gives us a good idea, with thousands of editions of U.S newspapers from the period digitised.

Breaking the news of rebellion in Ireland.

The first news Americans would have heard of rebellion in Ireland was published on 25 April, the day after the uprising in Dublin had commenced. Depending on the newspaper they were reading though, they may have believed the rebellion had been stopped in its planning stages. Reporting on the capture of Roger Casement and the sinking of a German arms shipment of the southern coast, The Sun in New York told readers that “An attempt to stir up a ‘revolution’ in Ireland was nipped in the bud when a German auxiliary cruiser, carrying a strong load of German sailors and loaded with stores of rifles and ammunition, was sunk off the coast of Ireland by British patrol warcraft.”

Claims that the rebellion had been “nipped in the bud” were totally at odds with the front pages of evening newspapers however, with The Evening World in New York announcing that ‘Irish in Dublin rise in revolt!’. The paper reported that the Post Office had been seized by Irish revolutionaries, but was “recaptured by troops.” The information of the paper, and other U.S outlets, was largely second-hand information from London. The rebellion was spoken of in the past tense, coming across as more of a riot than a political uprising. To The Evening World “A revolution in Ireland, planned by the German Government, brought about a terrific riot in Dublin yesterday in which twelve citizens were killed by British soldiers and four or five soldiers were killed by the rioters.”

Oklahoma City Times, 29 April 1916.

As news of the rebellion broke in the U.S, different versions of what was happening in Dublin spread too.

The Washington Herald for example ran a story on the front of its April 26th edition, filed from New York, that indicated a belief there among Irish Americans that the rebellion was proving successful:

There was a general report today in circles that have been interested in Irish Nationalistic propaganda that the Dublin insurrection had been almost completely successful, and that the Irish Volunteers had captured and held as hostage Lord Wimborne, Lord Lieutenant for Ireland, and other high English officials.

The question of blame.

Almost instantly in the American press, as in Britain, the blame for the Dublin violence was firmly placed on the shoulders of Imperial Germany. The rumour of heavy German involvement in orchestrating the violence remained rife throughout the week long rebellion. The Democratic Banner, on 28 April 1916 led with a front page story that ‘Irish Waters are Swarming with German Submarines’, going on to claim “The entire Irish sea and the Atlantic waters to the west and south of Ireland are swarming with German submarines, whose sole task is to sink every troop transport destined for Ireland to quell the rebellion.”

Some very German looking ‘Irish Patriots’ on the front of the Washington Herald, 1 May 1916.

Not content with German submarines in the Irish seas, some news sources began to make claims that German bodies were being discovered in the rubble of Dublin. On 1 May, the New York Tribune noted that “‘bodies of two German leaders reported found in Dublin.” According to the paper there were rumours that German bodies had been found in the rubble of Sackville Street. This was likely misinformation coming from London outlets, but it was often taken at face value.

Interestingly, Jim Larkin also took quite a lot of blame for the events in Dublin. Larkin had left Dublin for America in 1914, following the defeat of the Dublin workers. In America he had thrown himself into radical politics in New York, becoming involved with the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World trade union. One newspaper, The Daily Capital from Oregon, noted that:

Just how deep James Larkin, the turbulent Irish labour leader, and his followers are involved in the Irish revolt is not known, but it is not to be doubted that the man who preached firey opposition to government in 1913 will take advantage of the disturbances in Ireland.

The strength of Larkin’s followers in Ireland was grossly exaggerated, with the El Paso Herald for example claiming on 29 April 1916 that the “rebel forces numbered about 12,000, of which 2,000 were Larkinites and 10,000 were Sinn Féiners.” In reality, there were about 1,500 rebels out in Dublin, and the Irish Citizen Army could only dream of 2,000 armed members in revolt!

Key personalities of interest to the American media.

There was huge interest in the story of Countess Markievicz among the American press, with her ‘riches to rags’ story grabbing the public imagination. It was alleged by The Evening World in New York that she had shot six rebels who refused to follow orders, and they noted that “in mans clothing and flashing a brace of revolvers” she had led an attack on the Shelbourne Hotel.

Allegations against the Countess repeated in a New York newspaper.

A name which appeared again and again the American press was that of James Mark Sullivan. Sullivan was an Irish-American lawyer and former Minister to Santa Domingo, not to mention a film director who had established the Film Company of Ireland in March 1916, only months before the insurrection, and ironically the offices of the Film Company went up in flames during the uprising. Sullivan was arrested in Dublin, and of course the arrest of a former American diplomat was a huge story in the states. Sullivan spent some time imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, but was ultimately released. America was at this point ‘neutral’ in the First World War, and so the detention of a high profile U.S figure was perhaps something the British authorities were eager to avoid. Sullivan returned to the U.S, but he pops up again in the War of Independence period in Dublin. Eamon Broy, who worked as an agent for Michael Collins inside Dublin Castle remembered a party at Sullivan’s house in Dublin during the War of Independence in his Witness Statement many years later:

Apples and oranges were laid on a table to make the letters “I.R.A.” and we all enjoyed ourselves for that evening as if we owned Dublin. Tom Cullen spoke there and said that we would all die forMick Collins, “not because of Mick Collins, but because of what he stands for”. Mick was persuaded to recite “The Lisht”, which he did with his own inimitable accent. When he was finished, there was a rush for him by everybody in the place to seize him.

In later years Sullivan retired to Florida in the United States, but upon his death his body was taken to Dublin and buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. He is certainly a forgotten figure of the revolutionary period, and you have to wonder how with that kind of story!

The leadership figures caused some confusion for the press, with claims Connolly had died during the rebellion, and Patrick Pearse widely named ‘Peter’. The Day Book,a popular Chicago newspaper noted that “The backbone of the rebellion was broken when James Connolly, ‘General of the Irish Army, was fatally wounded at Liberty Hall. When Peter Pearce, leader of the rebels, was wounded in the leg most of his followers surrendered.”

The response of Irish America to events in Dublin.

The Kentucky Irish American makes its feelings known, May 1916.

In New York, it was reported that a meeting of the United Irish League of America condemned the rebellion, but that it was interrupted by several men and women, while ‘outside of the hall’ scores cheered Sir Roger Casement and Germany and “loudly denounced John Redmond, leader of the Irish nationalists in the British parliament.” A meeting was held in New York in support of the aims of the rebellion, with a reported attendance of 1,500 in many newspapers. Deutschland Uber Alles, the Wearing of the Green and the American national anthem were all performed by a band, and leading figures of the Irish American community such as the exiled radical John Devoy spoke.

The Kentucky Irish American made its feelings on executions perfectly clear on 6 May 1916, 6 days before James Connolly would be shot tied to a chair in Dublin: “If the sequel to the fighting at Dublin is wholesome hanging and shooting of Irishmen by English officials, there is no doubt of the outcome. Under such circumstances a war of revolution is a foregone conclusion.”

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.