[A sequel to this article can be read here]

In the early half of the twentieth century, there were roughly 3,700 Jews living in Ireland. This represented about 0.12% of the total population. Though their numbers were minuscule, members of the the Jewish community were disproportionately active in the fight for Irish independence. Melisande Zlotover in his 1966 memoir ‘Zlotover story: A Dublin story with a difference’ assessed the overall situation by writing that Dublin’s Jews “were most sympathetic [to the fight for Independence] and many helped in the cause”.

These included:

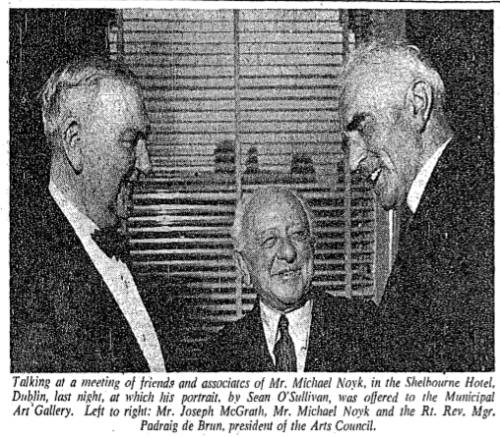

Michael Noyk (1884–1966) was born in Lithuanian town of Telšiai and moved to Dublin with his parents at the age of one. An Irish Republican activist and lawyer, he most famously defended republican prisoners during the War of Independence and afterwards. In the 1917 Clare East by-election he was a prominent worker for Eamon de Valera and in the 1918 general election was election agent for Countess Markievicz and Seán T. O’Kelly. He was later involved in renting houses and offices for all the ministries established under the first Dáil. During the War of Independence he regularly met Michael Collins in Devlin’s pub on Parnell Square and helped to run the republican courts. In 1921 he was to the fore in defending many leading members of the IRA, including Gen. Seán Mac Eoin and Capt. Patrick Moran, the latter of which was executed for complicity in the shooting of British intelligence officers.

While Arthur Griffith’s early anti-Semitic comments (c.1904) are frequently recalled, it should be noted that he was an extremely close friend of Noyk’s from 1910 onwards and he remained Griffith’s solicitor until his death in 1922. So close did Griffith’s relationship with Noyk become that his own daughter would act as a flower girl at Noyk’s wedding as Manus O’Riordan reminded us in an excellent 2008 article.

In later years, Noyk became a founder-member of the Association of Old Dublin Brigade (IRA) and a member of the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Committee. Keenly interested in sport, he played soccer in his youth for a team based around Adelaide Road and was for many years the solicitor to Shamrock Rovers. He died on 23 October 1966 at Lewisham Hospital in London. A huge crowd, including the then taoiseach, Seán Lemass, attended his funeral and the surviving members of the Dublin Brigade rendered full IRA military honours at his graveside. He is buried in Dolphin’s Barn cemetery.

Robert Emmet Briscoe (1894–1969) was a Jewish Dublin-born republican and businessman who most famously ran guns for the IRA during the War of Independence. Named after revolutionary leader Robert Emmet, his father, a steadfast Parnellite called another son Wolfe Tone Briscoe. Politicised after the Easter Rising, Robert attended meetings of Clan na Gael in the United States, meeting Liam Mellows, who influenced his return to Ireland (August 1917) to join the headquarters staff of Na Fianna Éireann. The clothing factory that Robert Briscoe opened at 9 Aston Quay, and a subsequent second workshop in Coppinger’s Row, both served as headquarters for clandestine Fianna and IRA activities before and during the War of Independence. Unknown to government authorities owing to his lack of prior political involvement, Briscoe engaged in arms-and-ammunition procurement and transport, and gathering of intelligence. Transferred to IRA headquarters staff (February 1920), he was dispatched by Michael Collins to Germany, where, with his knowledge of the language and country, he established and oversaw a network of arms purchase and transport. He maintained a steady flow of matériel after the July 1921 truce, and from 1922 to the anti-treaty IRA, with which he maintained links for some years after the civil war. Returning to Ireland after the 1924 general amnesty, he managed the Dublin operations of Briscoe Importing, a firm already established by two of his brothers.

During the summer of 1926 the IRA raided the offices and homes of moneylenders in both Dublin and Limerick. Manus O’Riordan wrote that:

Those who were raided were indeed predominantly Jewish, but the IRA explicitly stated that their attack was on moneylending itself, “not on Jewry”.

Historian Brian Hanley summed up the situation well when he said that the IRA:

…were supported in their claims by the prominent Jewish politician in Ireland, Robert Briscoe of de Valera’s Fianna Fáil Party. He argued that he did not see the raids as anti-Semitic, and wished it to be known that he and ‘many other members of the Jewish community’ abhorred moneylending and expressed his admiration for the IRA’s attempts to end ‘this rotten trade’.

A founding member of Fianna Fáil (1926), he served on its first executive committee, and worked on constructing the party’s national constituency organisation, transporting party workers countrywide in his recently purchased motor car. Defeated in the June 1927 general election and in an August 1927 by-election occasioned by the death of Constance Markievicz, in the September 1927 general election he was elected to Dáil Éireann, becoming the first Jewish TD, and commencing an unbroken tenure of thirty-eight years, representing Dublin South (1927–48) and Dublin South-West (1948–65). Twice lord mayor of Dublin (1956–7, 1961–2), he made a spectacularly successful whistle-stop tour of the USA (1957) – the first of several official visits, trade missions, and speaking tours – lauded by Irish- and Jewish-Americans as Dublin’s first Jewish lord mayor.

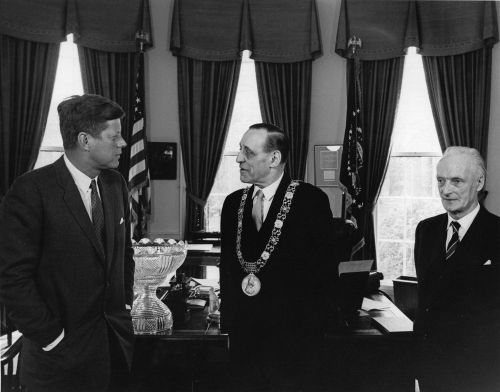

JFK meeting with IRA veteran Robert Briscoe, Lord Mayor of Dublin. 26 March 1962. Credit – jfklibrary.org.

Estella Solomons (1882–1968), who “hailed from one of the longest established Jewish families in Dublin”, was a distinguished artist active with the Rathmines branch of Cumann na mBan (Wynn, 2012, p. 60). One of her first jobs was distributing arms and ammunition which she kept hidden under the vegetable patch at the family home on Waterloo Road. (Wynn, 2012, p.60) When her sister visited from London with her British Army husband,, Estella stole his uniform and passed it onto the IRA. Solomons sheltered IRA fugitives in her studio during the War of Independence, and concealed weapons under the pretence of gardening. Estella’s IRA contact was a milk delivery man, who acted as a perfect cover for moving arms and gathering information. She persuaded him to teach her to shoot, in exchange she painted a portrait of his wife. Taking the anti-Treaty side and sheltering Republicans during the Civil War, her studio was often raided by Free State troops.

Solomons was elected an associate of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in July 1925, but it was not until 1966 that Solomons was elected an honorary member. Her work was included in the Academy’s annual members’ exhibition every year for sixty years. As her parents were opposed to her marrying outside her faith, it was not until August 1925, when she was 43 and her husband 46, that she married Seumas O’Sullivan, the editor and founder of the influential literary publication Dublin Magazine.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.