There have been a small but not insignificant number of reactionary murders in Dublin and on the island of Ireland since the 1920s. I have tried to compile a list of these here. They are divided up into areas of anti-Semitism, homophobia and racism.

I have purposely not included murders in regard to nationality (Irish/English) or religion (Catholic/Protestant), as due to this island’s history, these are a completely different matter.

Obviously not all murders of ‘foreign nationals’ in Ireland can be considered ‘racist’. Those that have been included all had a racial element to them though.

Anti-Semitism:

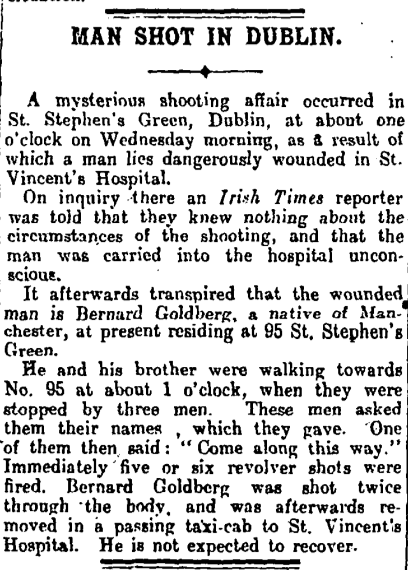

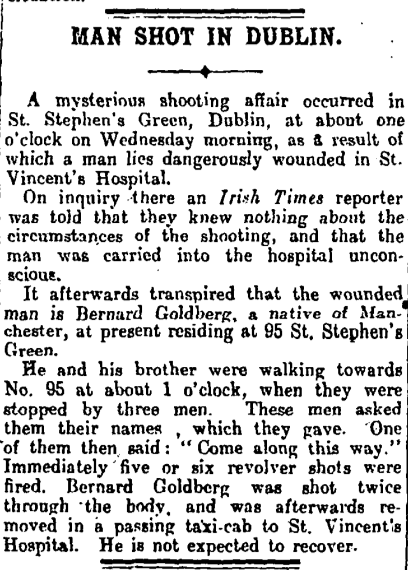

31 October 1923: Bernard Goldberg, Dublin

Golderg (42), a Manchester jeweller and father of four, was shot on St Stephen’s Green after three men had stopped him and his brother Samuel and demanded their names.

The Weekly Irish Times, 3 November 1923.

14 November 1923: Emmanuel Kahn, Dublin

Dublin-born Kahn (24) of Lennox Street, was gunned down in Stamer Street in Portobello as he returned home after an evening playing cards. David Millar, who was with him in the Jewish Club in Harrington Street, was also shot in the shoulder but managed to stagger home.

The principal instigator of these two murders was Commandant James Patrick Conroy, who claimed to have resigned from the army in December 1924 because he disagreed with the policy of the then government. He fled to Mexico and then to the United States, along with with two other suspects, after the incidents. No-one was ever convicted. A curious footnote to the whole affair was found in remarks in the Dail in February 1934, when Fianna Fail finance minister Sean McEntee claimed that one of the killers was walking free, and was a member of the fascist-style Blueshirts organisation.

Sexuality:

3 June 1979: Anthony McCleave, Belfast

McLeave was murdered in one of the city’s best known ‘cruising areas’. He was found with his head rammed onto a spike on a protective bollard outside the fire station on Chichester Street. The RUC closed the case within twenty-four hours but was it reopened after a campaign by the Northern Ireland Gay Rights Association (NIGRA) which was backed by the McCleave family. No-one was ever charged with his death.

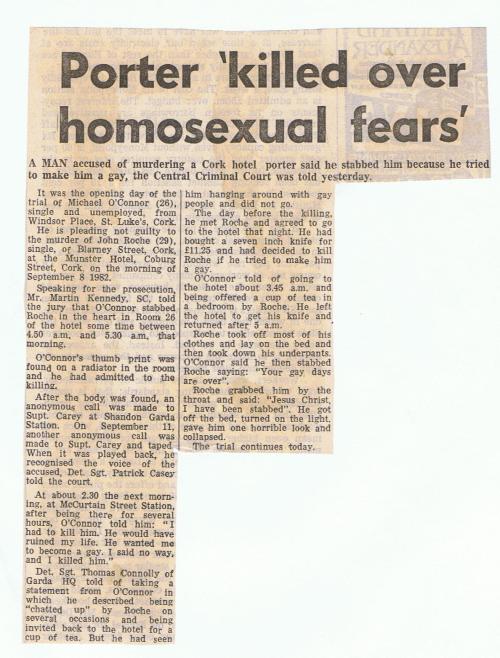

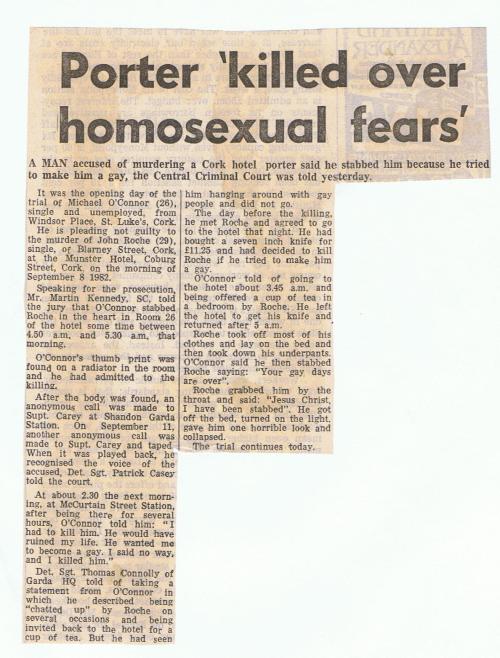

8 September 1982: John Roche, Cork

Roche (29), a gay man, was murdered by Michael O’Connor in the Munster Hotel in Cork City. The victim, who worked in the hotel as a night porter, was found tied to a chair in one of the bedrooms. He had been stabbed in the chest with a 15cm (6″ ) knife. Repulsed by the victim’s alleged advances O’Connor stabbed Roche, telling him “Your gay days are over”. Michael O’Connor was found by a jury to be not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter.

Evening Press, 11th May 1983. Credit – Irish Queer Archive

November 1982: Henry McLarnon, Ballymena, Co. Antrim

McLarnon (22), father of two, was murdered by Richard John Nicholl in Ballymena. In court, Nicholl said that McLarnon had lured him to the quarry where he had made a sexual advance. In response, he stabbed McLarnon with a work tool. There was controversy at the trial when Nicholl was convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter and received a two-year suspended sentence. In 2002, Nicholl took his own life.

21 January 1982: Charles Self, Dublin

Self (33), a RTE set designer originally from Glasgow, was murdered in his flat on Brighton Avenue, Monkstown. He was found with knife wounds to his chest and neck. The investigation led to almost 1,500 gay men being questioned, photographed and fingerprinted at Pearse Street Garda Station. For many in the gay community, it felt like the police were more interested in compiling dossiers on gay men rather than solving the brutal murder. No-one was ever charged.

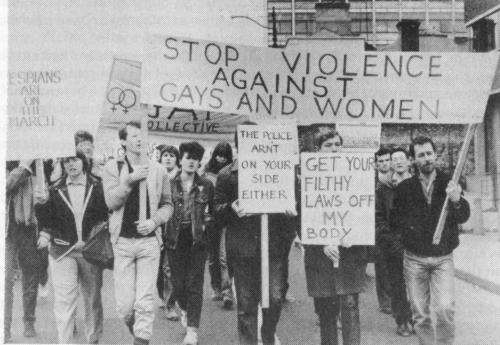

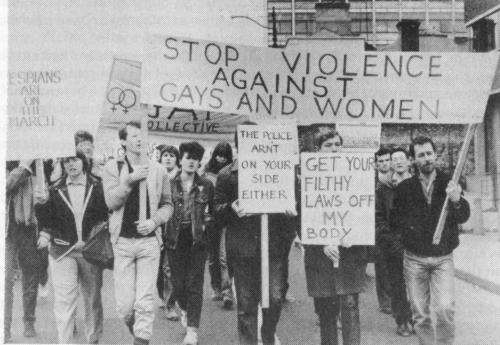

9 September 1983: Declan Flynn, Fairview Park, Dublin

Flynn (31), an Aer Rianta worker, was beaten to death by a group of five teenagers in a ‘gay-bashing’ incident in Fairview Park. The gang had been responsible for a spate of attacks on gay men in previous weeks and it emerged that they used the park to target members of the gay community. As Flynn lay dying, £4 from his pocket and his watch was stolen. In court, one of the teenagers admitted that “we were all part of the team to get rid of the queers from Fairview Park”. The five male teenagers were all released on a suspended manslaughter charge with Judge Sean Gannon saying “This could never be regarded as murder”.

Fairview Park Protest March photographed on Amiens Street by Derek Speirs, courtesy “Out For Ourselves” (Womens Community Press, 1986). Credit – Irish Queer Archives

7 February 1997: David J. Templeton, Belfast

Templeton (43) was a minister of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland who was murdered after he was ‘outed’ as a gay man by the Sunday Life newspaper. Three men wearing balaclavas, believed to have been UVF members, entered his home in north Belfast and beat him with baseball bats with spikes driven through them. He died in hospital several weeks later.

(Note: Some websites list Darren Bradshaw, a gay men and RUC officer, murdered in 1997 by the INLA as a homophobic murder. However, it is probably fair to say that he was killed because of his occupation rather than his sexuality?)

7 September 2002: Ian Flanagan, Belfast

Flanagan (30), a civil servant, was battered with a wheel brace and stabbed with a kitchen knife in the grounds of Barnett’s Demesne park. His two killers ‘deliberately set out to target a member of the gay community’. Raymond Taylor was sentenced to 13 years and Trevor Peel was given 14 years.

3 December 2002: Aaron (Warren) McCauley, Belfast

McCauley (54), a nurse for over 30 years at Muckamore Abbey hospital, was lured and battered to death in a well-known ‘cruising’ spot. He was found in an alley just 30 yards from the Church Lane toilets and died two days later without regaining consciousness. The attack was believed to have been motivated by homophobia. His injuries consisted of a blow to the side of the head and another to the throat. Nobody was ever charged.

23 March 2008: Shaun Fitzpatrick, Dungannon, Co. Tyrone

Fitzpatrick (32), a supermarket manager, was kicked to death after leaving Donaghy’s Bar by two homophobic Lithuanian men. The court heard that when Mr Fitzpatrick’s body was found, he had been beaten so savagely that paramedics thought he had been shot. The pair were sentenced to to life imprisonment.

5 February 2012: Andrew Lorimer, Lurgan, Co. Armagh

Lorimer (43), a former canoeing instructor and security guard, was kicked and beaten to death with a hammer in his own flat in Portlec Place. Three men were charged with the ‘homophobic murder’.

Race:

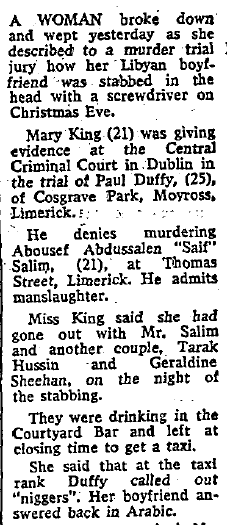

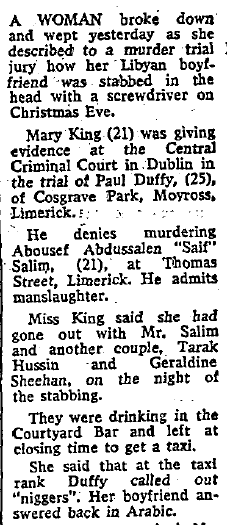

24 December 1982: Abousef Abdussalem Salim, Limerick

Salim (21), a Libyan trainee airplane pilot, was stabbed in the head with a screwdriver by a Limerick man who screamed ‘nigger’ and ‘bastard’ before the attack at a taxi rank on Thomas Street. The attacker was sentenced to five years penal servitude for manslaughter.

The Irish Independent, 3 February 1984.

24 June 1996: Simon Tang, Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim

Tang (27), a Chinese businessman, was beaten and robbed as he left his takeaway business in Carrickfergus. Described by police as a ‘racist attack’, the father of two had his watch and the night’s takings stolen. He was taken to hospital but later died from his injuries. In 2002, two men were remanded in custody charged with the murder but they were later released. No-one has been convicted of the killing.

27 January January 2002: Zhao Liu Tao, Dublin

Tao (29), a Chinese student of English, was attacked by a five-member gang in Beaumont, on the northside of the city. The gang were reported as making racist taunts and a fracas followed. One of the youths struck Mr Zhao with a metal bar. He died three days later in Beaumont Hospital. An 18-year-old youth was sentenced to four years detention, the last two years were suspended because of the perpetrators age and the fact that he had no previous convictions.

29 August 2002: Leong Ly Min, Dublin

Min (50), who had been living in Dublin since 1979 after fleeing Vietnam, was assaulted in Temple Bar. He suffered head injuries and later died in hospital. Two men were charged in relation to this crime. At the time it was reported by the media that there might have been racist insults used during the attack.

Anti-Racist protest after murder of Leong Ly Min. Credit – An Phoblact

23 February 2010: Pawel Kalite and Marius Szwajkos, Dublin

Kalite (28) and Szwajkos (27), Polish nationals, were racially abused before being stabbed in the head with screwdrivers on Benbulben Road, Drimnagh. Two Dublin teenagers are currently serving mandatory life sentences.

2 April 2010: Toyosi Shittabey, Dublin

Shittabey (15), a talented footballer originally from Nigeria, died after being stabbed in Tyrrelstown, Dublin 15. A row with “racist undertones” began outside the house of Paul Barry at Mount Garrett Rise between Paul, his brother Michael and a group of black males and white females after one of the females asked Paul for a cigarette lighter and he had refused. Believing a phone was taken by the group, Mr Barry and his brother Paul went into his house to fetch a knife and then pursued them in a car. They encountered the group of teenagers at a roundabout in Tyrrelstown. Shittabey, known as “Toy”, urged his friends to walk away again but was stabbed in the heart by Paul Barry The two brothers were charged with murder. Paul Barry (40) committed suicide the day before the trial was due to begin. His brother Michael (26) was acquitted because it was his brother inflicted the stab wound. It transpired that Paul had been involved in another racist knife attack ten years previously.

![Gay Health Action (GHA) 60's Night Benefit Disco. Flyer, designer unattributed. 1985 [Ephemera Collection, IQA/NLI]](https://comeheretome.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/902593_495988767121212_24289184_o.jpg?w=500&h=354)

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.