It may come as a surprise to some, but Daniel O’Connell, who although in his political life deplored the use of violence, took part in and won a duel in Bishops’ Court, County Kildare in 1815. His opponent was an experienced duellist by the name of John D’Esterre and it was widely regarded that O’Connell would lose. D’Esterre, a former royal marine was a crack shot of whom it was said he could snuff out a candle from nine yards with a pistol shot. It wasn’t his first duel, himself having challenged an opponent in court to a duel only two years previous, though on that occasion, he backed down at the last minute and the duel did not take place.

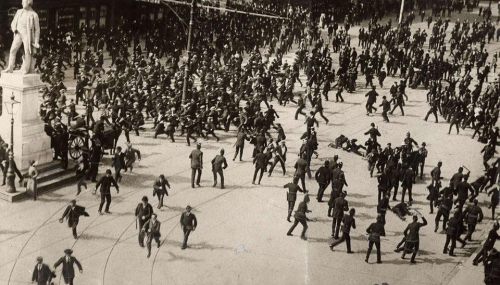

The cause of the duel was a political speech made by O’Connell to the Catholic Board on 22nd January, 1815 in which he described the ascendancy-managed Dublin Corporation as beggarly. D’Esterre, at the time nearing bankruptcy took this as a personal insult and sent O’Connell a letter demanding a withdrawal of the statement. When this letter went unanswered, he sent a second letter which O’Connell responded to, asking D’Esterre if he wanted to challenge him, why hadn’t he yet done so. D’Esterre set out to provoke O’Connell into a challenge, and at one stage ventured out onto the streets of Dublin looking for him, horsewhip in hand only to be forced into seeking refuge in a sympathetic home, such was the crowd that began to follow him around.

Days passed, and the bubbling tension between the two had become the talk of the town and finally a challenge was laid down by D’Esterre, and a letter sent to O’Connell’s second. Jimmy Wren’s “Crinan Dublin” names Sir Edward Stanley of 9 North Cumberland Street as D’Esterre’s second and an Irish Press article from 1965 names Major MacNamara a protestant from Clare as O’Connell’s.

The duel was to take place on Lord Ponsonby’s demesne at Bishops’ Court, Co. Kildare on the afternoon of the challenge and the weapons of choice were pistols, provided by a man named Dick Bennett, and both pistol’s had notches on their butts to denote kills made by the weapon. Both parties were limited to one shot each, leading Stanley to retort “five and twenty shots will not suffice unless O’Connell apologises!” A light snow shower fell as a crowd gathered and the men took their places. D’Esterre shot first, but miscalculated and fired too low, and in doing so, missed. O’Connell returned fire, hitting and wounding D’Esterre in the groin, the bullet lodging in the base of his spine. D’Esterre fell, and the crowd roared. As much of a crack shot as D’Esterre was, O’Connell was a better one, having trained in case such an eventuality might come about.

As they made their way back to Dublin, the news spread before them and the route home was lined with blazing bonfires. Although O’Connell boasted that he could have placed his shot wherever he wanted, he did not intend to kill D’Esterre, and was shaken to find that the man had bled to death two days later. D’Esterre, as was said was bordering on bankruptcy, and on his death, bailiffs moved in and seized anything of value from his home. Saddened by the outcome, O’Connell offered to half his income with D’Esterre’s family but the offer was all-but-refused, however, an allowance for his daughter was accepted, which was paid regularly until O’Connell’s death over thirty years later. He would never duel again, and from then on often wore a glove or wrapped a handkerchief around the hand that fired the fatal shot while attending church or passing the door of D’Esterre’s widow.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.