This cartoon is taken from a 1908 edition of The Lepracaun, a satirical magazine founded by the cartoonist Thomas Fitzpatrick in 1905. A monthly publication, it featured some biting satire and James Joyce was among its contributors. This cartoon from 1908 deals with the issue of relations between the Guinness Brewery and other brewers in the city, and relates to the manner in which Guinness would not allow their traders to use Guinness labels if they continued to supply any other porter or stout, something which led to their profits almost doubling in a period of just over ten years.

Peter Paul Lens was an English eighteenth century miniature painter, as was his father Bernard Lens, and his brother Andrew Benjemin. An artist of some renown, we know from the Dictionary of Irish Artists that he came to Dublin in, or shortly prior to, the year 1737. Numerous examples of the work of Peter Lens can be found online today, such as this miniature painting of a gentleman which recently sold at auction in England for £480.

Lens is a fascinating character owing to his prominence in a club known as ‘The Blasters’, a club which managed to become the subject of a report by a Committee of the House of Lords in March 1738 owing to its supposed Satanist practices, which led to Lens fleeing the country for England. This club was similar in many ways to the infamous Hellfire Clubs of the period. One contemporary described Lens as a “reprobate… An Ingenious Youth”, and his activities and the activities of The Blasters even led to condemnation from Jonathan Swift. Swift refereed to club as “a brace of monsters called blasters, or blasphemers or bacchanalians”, and listed Lens as one of its leading figures.

A miniature portrait of Bernard Lens (Father of the artist) by Peter Lens. This image is taken from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection.

Gabrielle Williams wrote an article biographical sketch of the Lens family for The Irish Times in 1972, noting that the father of Peter Lens served as a miniaturist to George I and George II, and outlining that Peter “is even attributed with having founded the Irish school of miniaturists, and certainly his influence was strong.” Williams noted that Peter’s lifestyle was “gay and somewhat foolhardy”, a persona one imagines to be right at home in the Dublin of the eighteenth-century!

In his study Witchcraft and Black Magic (1946), the clergy man Montague Summers noted that In Ireland “one of the vilest and most notorious of these demonic societies was The Blasters, a miniature painter, and a professed Satanist, who openly proclaimed himself a votary of the Devil”, and noted that in the eyes of Bishop George Berkeley what this club engaged in were “no ordinary profanities or oaths uttered in the debauch of drink or the heat of passion, but a studied, deliberate and public worship of the Devil.” Berkeley was horrified that Lens had “publicly drank to the devil’s health” and in a letter to Berkeley from another Bishop, Bishop Forster, it was noted that “the zeal of all good men for ye cause of God should rise in proportion to ye impiety of these horrid blasphemers.”

Eighteenth-century Dublin contained many public houses and taverns which hosted clubs of this kind. The Hellfire Club was said to meet at the Eagle Tavern at Cork Hill for example. A 1963 article on the club for The Irish Times by Lord Oxmantown claimed that when the meetings would break up, “Satan, a member of the club, dressed in the skin, tail and horns of a cow, would charge forth into the streets to the terror the locals.” Other clubs like Daly’s Club saw their share of debauchery in eighteenth-century Dublin too.

The seriousness with which clubs like The Blasters were taken is evidently clear from the fact that these society were discussed at the level of the House of Lords. The Report from the Lords Committee for Religion, dated March 10 1738, offered fascinating insight into how this society was viewed by those in authority, and noted that:

As Impieties and Blasphemies of this Kind were utterly unknown to our Ancestors, the Lords Committee observe, that the Laws framed to them must be unequal to face such enormous Crimes, and that a new Law is wanting more effectively to refrain and punish Blasphemies of the kind.

The entry on Lens in the Dictionary of Irish Artists notes that following this report “It was ordered that he be prosecuted, and warrants were issued for his arrest. He left Dublin and was pursued through various parts of the country, but he managed to evade capture and got safely over to England.” Lens continued his career in England.

The demise of The Blasters, and indeed the ‘Hellfire Club’, did not mark the end of infamous and blasphemous clubs in the city. In March 1771 the pages of the Freeman’s Journal reported on the establishment of a club styling itself the ‘Holy Fathers’, a blasphemous club similar in many ways to those of the earlier eighteenth-century. Writing in 1867, Richard Robert Madden noted that “most of the members of this club were young men of fortune”, and that it was said that this group also toasted the Devil.

Posted in Dublin History | 1 Comment »

James Spain was a 22-year-old Dubliner and member of the anti-Treaty IRA when he was shot dead by the Free State Army in November 1922. The killing took place in the area then known as Tenters Field off Donore Avenue, only minutes away from where Spain grew up. There is no plaque or monument to mark the spot of this incident. We have previously covered Noel Lemass and William Graham.

James was born on 18 November 1900 to Francis and Christina Spain, both originally from Dublin.

The 1901 census shows that the family were living at 63 Harty Place off Clanbrassil Street Lower. Francis (30) was a boot maker while his wife Christinia (24) looked after their three sons – Joseph (4) Francis Jr. (2) and James (4 months). All were Roman Catholic.

Ten years later the family had moved to 9 Geraldine Square off Donore Avenue. The 1911 census tells us that Francis (41), still a boot maker, and his wife Christina (35) were now living with their six sons and one daughter. These being Joseph (14), Francis Jr. (12), James (10), Annie (7) who were all at school along with Michael (5), John (3) and Patrick (1). Francis had Christina had been married for fifteen years.

At the time of his death in 1922, James Spain was listed as a upholster living at 9 Geraldine Square which corresponds with the census records. Relatives told the subsequent inquest that he had escaped from a military prison three weeks previously. His grave states that he was 1st lieutenant of A Company, 1st Batt. of the Dublin Brigade IRA.

Spain was a part of a 20-30 strong IRA team who launched a major military attack on Wellington Barracks (now Griffith Barracks) on the night of 8 November 1922. The principal attack was delivered at the rear of the barracks while shots were also fired from house-tops in the South Circular Road area.

The Irish Times, the following day, reported that the neighborhood was the:

” scene of a miniature battle. Thompson and Lewis guns answered each other with equal vigour, the sounds of the firing being heard all over the city … For nearly an hour ambulances were busy taking the wounded to hospital.

A total of 18 soldiers were hit. One was killed instantly and 17 were badly injured.

Republicans like Spain tried their best to flea the area and escape arrest. John Dorney writing in The Irish Story summarised that:

The Republicans made their escape across country, through the villages of Kimmage and Crumlin, pursued by Free State troops. They were seen carrying two badly wounded men of their own.

Spain ran north, possibly out of instinct, towards the Donore Avenue area and his home. Witnesses claim that he was dragged out of a house by soldiers and shot in Tenter Fields while the Army’s official version of events claim that he was shot in the Fields after he refused an order to stop running.

The Irish Times of 10 November 1922 reported on the events leading up to his death. Two hours after the attack on the barracks, Spain ran up to 22 Donore Road. Here a woman, Mrs. Doleman, was feeding her birds in the yard. He shouted “for god’s sake, let me in” and fell just as he got inside the gate but managed to make it the kitchen where he collapsed onto a sofa. According to Dolenan, he was only there for a few minutes before a group of Free State soldiers ran into the house and grabbed Spain. Mrs. Doleman heard shots a few minutes after.

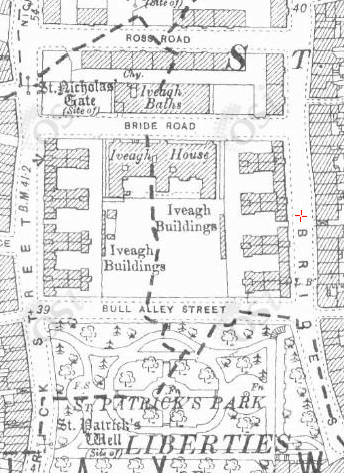

Map showing Geraldine Sq. in the top left hand corner (where Spain was grew up), Tenters Field (where Spain was shot) and Susan Terrace beside it (where his body was found)

As often in these cases, this is where the story diverges slightly.

At the inquest, an unnamed member of the Free State Army reported that himself and five riflemen in a Lancia car came across one of the attackers (Spain) in Tenter Fields and “called on him to halt four or five times”. After this request was denied, they shot him and the man fell.

Either way, the body of this young 22 year old local was found at No. 7 Susan Terrace at the edge of Tenter Fields. He had been shot five times.

The Irish Independent on 11 November 1922 wrote:

The remains of Mr. James Spain … were last night removed from the Meath Hospital to the Carmelite Church, Whitefriar St. A man who was introduced at a previous protest meeting as Mr. O’Shea of Tipperary mounted the ruins in O’Connell St. last night and addressing those about him, asked that the meeting of protest against the treatment of prisoners be adjourned as a mark respect to the late Mr. Spain.

Two days later, the same newspaper reported on the funeral:

A number of the Cumann na mBan marched behind the hearse and there was a large cortege. The remains were received in the mortuary chapel by Rev. J. Fitzgibbon. A large numbers of wreaths were placed on the grave and three volleys from firearms were fired over the grave. The chief mourners were – Mr. F. Spain (father), Mrs. Spain (mother), Joe, Frank, Mickie, Jack, Paddy and Peadar (brothers), Annie, Molly and Crissie (sisters), Maggie and Mickie Spain (cousins), Annie and Mary Spain (aunts) and Jack Spain (uncle)

Spain was buried in the family plot in Glasnevin. Thanks to Shane Mac Thomais (of the Glasnevin Museum) for getting in touch and sending me the image of the grave.

James Spain was just one of dozens of young anti-Treaty IRA men who were killed by the Free State in Dublin from August 1922 to August 1923. Of the 26 murders as far as I can work out, 16 are marked by small monuments where the bodies were found.

If you have anymore information about James Spain, please get in touch by leaving a comment or emailing me at matchgrams(at)gmail.com

Posted in Dublin History | 48 Comments »

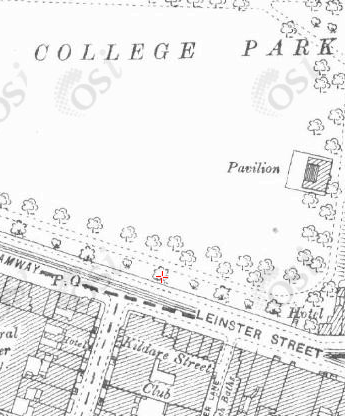

There is an enduring legend that during one game of cricket in Trinity College, a stray ball broke a window of the exclusive Kildare Street Club at the corner of Kildare Street and Nassau Street. The story is usually associated with the legendary British Cricket player W.G. Grace who did visit Dublin a number of times in the late 19th century.

In 1897, witnesses are on the record saying hit a ball from College Park in Trinity over the fence and onto Nassau Street. Since then however, the story has grown legs and numerous individuals have been credited with his achievement.

James Joyce was obviously a fan of the legend as he wrote in Ulysses (1922):

Heavenly weather really. If life was always like that. Cricket weather. Sit around under sunshades. Over after over. Out. They can’t play it here. Duck for six wickets. Still Captain Buller broke a window in the Kildare street club with a slog to square leg.

An online Joyce website has done extensive research on trying to find out who this Bulller referenced could have been.

Kildare Street Club in 1860. Credit – http://archiseek.com

Stephen Gwynn in his Dublin Old And New book, published in 1938, makes reference to the incident :

(In Trinity) more than one lusty man has lifted a ball to leg and broken a window in Nassau Street: indeed it sticks in my memory that in one of the first Australian teams, when Spofforth was dreaded as a demon bowler, a handsome giant, Bonner, hit a ball off an Irish bowler, to a measured distance of 175 yards

Sports journalist MVC in the Irish Independent on 19 July 1945 wrote:

Famous Cork County cricketer Major Parry … often delighted my young heart with some mighty hitting at College Park. Parry may not have accomplished the legendary feat of breaking a window in the Kildare Street Club but more than once I remember having to duck to avoid being decapitated by fierce hooks that went straight from the bat to the Nassau Street wall without the touching the ground. By way of a chance, can anybody tell me if the Kildare Street Club ever did suffer such an assault and by whom – or is the story as apocryphal as the one about somebody hitting from Rathmines to break the Town Hall Clock

He received a reply from an Enniskerry-based reader the following week:

A window of the Kildare Street Club was broken by a bat but (so far as I know) not by a cricket ball from College Park. In May 1922, I was in Kildare St. when some Army footballers returning from a playing pitch to Oriel House (Westland Row) kicked their ball football in the street. One kick resulted in the smashing of a Kildare St. Club window. The ball was kicked by Capt. Charlie McCable and I think that later McCabe defrayed the glazing expenses.

An Irish Times writer, on a bus home, was retold the Grace story by a friend.

In the paper on 16 September 1954, he recounted the conversation with his companion:

“We are now passing the Kildare Street Club. Nearly a century ago, W.G. Grace broke a window in it with a slog to square leg”. My correction was instantaneous and stern. “It was not W.G. Grace. The man’s name was Tyndall, he was an Irishman, and it didn’t happen nearly a century ago”.

In the 1956 book Cricket in Ireland William Patrick Hone quotes Captain Fowler, the oldest cricketer member of the Kildare Street Club, as saying that the only window he ever heard of being broken “was when a sniper had a shot at Lord Fermoy and missed”.

In The Irish Times on 10 July 1956, ‘Skipper’ suggested that the feat was actually accomplished by a Scottish student:

Scotland were meeting Dublin University … in College Park, and finding themselves a man short, invited “RH”, who was then a student at Edinburgh Veterinary College, to play for them. He accepted, and during his inning he hit two balls into Nassau Street, one of which smashed a window in a cab parked on the roadway, while the other rebounded from the wall of the Kildare street Club. The ‘cabby’ was amply recompensed for the broken window and the balls in question were retrieved in the ordinary way.

An Irish Times article from 11 October 1972 adds even more elaborate details :

W.G. Grace hit a six from Trinity College Park which landed in the Earl of Meath’s custard, thus giving rise to the timeless saying “Waiter, there’s a cricket ball in my soup!”

But while a football and a snipers shot did break windows of the Kildare Street Club, it would seem that that the Cricket ball story is indeed just legend.

Posted in Dublin History | 3 Comments »

The Irish Independent, April 1st 1971.

On March 31st 1971, a small protest by activists from the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement grabbed nationwide media attention. Angered by the decision of the Seanad not to allow a reading for Senator Mary Robinson’s Contraceptive Bill which could have led to the legalisation of contraception, fifteen women who were accompanied by children made their way to the gates of Leinster House, forcing their way into the grounds. Shortly after 3pm, the women made their way through the Merrion Street gates, before a few of them snuck into the building through the open window of the male bathrooms!

Among the women who partook in the protest were the journalist Mary Kenny, Sinn Féin secretary Mairin de Burca and Margaret Gaj. Gaj was a fascinating character, born in Glasgow to Irish parents in the year 1919, she was a veteran of the women’s movement and many other progressive movements in Irish society. She also owned the popular restaurant and hangout Gaj’s on Baggot Street. In a 2011 obituary for Mrs. Gaj, Rosita Sweetman noted that ” trade unionists, aristocrats, lawyers, bank robbers, prostitutes, students, artists, prisoners, civil-rights activists and Women’s Libbers all rubbed shoulders around the scrubbed hardwood tables.”

The group made their way into the grounds of Leinster House singing ‘We Shall Not Conceive’ to the tune of ‘We Shall Overcome’, and were refused permission to speak to any Senators following the decision of the Seanad not to discuss the issue. One individual who did speak to the women was Joseph Leneghan, the Fianna Fáil T.D for West Mayo. The journalist Mary Kenny was among the protesting women, and raised the issue of his use of the term “whores knickers” in the Dáil with Leneghan. The Irish Times reported that “Mr Leneghan- he comes from Belmullet,said that knickers hadn’t come to his part of the country yet; they’d only reached Ballina.”

Leneghan went one better by offering to bring the women to the Dáil bar, and “he was preparing to lead them through the entrance but the attendant would only admit him and not the entourage.”

Three of the women (Mairin de Burca, Finn O’Connor and Hilary Orpen) noticed an open window they squeezed through, which led to the male toilets. Locking themselves in for some time, they succeeded in attracting the attention of several Senators who did come to speak to them. On being evicted from the premises, some of the protesters claimed to have been assaulted by Gardaí and registered complaints at Pearse Street Garda station.

While this invasion of Leinster House through the window of the toilets is a comical enough story, the women’s movement in the 1970s had serious teeth, and led many important progressive campaigns in Ireland, from opposing censorship (see this CHTM post on Spare Rib magazine) to the battle for contraception in Ireland. Not long after this event, the famed ‘Contraception Train’ action would follow, grabbing national and international attention.

Posted in Dublin History | 8 Comments »

Glasnevin Museum are currently playing home to a beautiful old tramcar, which is on loan from the National Transport Museum in Howth. With this being the year of the centenary of the 1913 Lockout, which involved Dublin tram workers, there is no more fitting time for Dubliners to see this iconic form of public transport. The tram is at Glasnevin until this Saturday, and was on-site for the anniversary of Jim Larkin’s passing yesterday:

I couldn’t resist getting a snap with the tram, which is bedecked with slogans of the union movement from the period:

Jer O’Leary, the Dublin actor who performs the role of Jim Larkin with great passion, done the very same. Last year I saw Ger deliver one of Larkin’s speeches to a class of schoolchildren in Ringsend, one of the areas in Dublin which was caught up in the labour dispute. Anyone who hasn’t can see Jer in action here.

Posted in Dublin History | Leave a Comment »

We’ve recently had some posts on the history of football hooliganism in Dublin, which have attracted considerable interest. It’s the tip of the iceberg with a lot more study to be done in the area, but over the course of my research I came across this pretty comical article from the Sunday Independent, of a Benny Hill like operation at Milltown which resulted in a mob attacking a bus in a case of mistaken identity.I’m a bit confused by the report though, as Miltown was the home of Shamrock Rovers at the time. Anyone know more about this one?

Posted in Dublin History | 1 Comment »

The Irish Press reports on the death of Jim Larkin. He is shown here being arrested on Bloody Sunday, 1913.

January 30th marks the anniversary of Jim Larkin, who died in 1947. The Irish Press reported on the day after his passing that it marked the end of an epoch in Irish history, and that “with him to the grave goes the turbulence and tumult of 1913.” Larkin was 72 years old at the time of his passing, and to this day remains a giant of not only trade union history in the city of Dublin but also the collective memory of the capital. On the day following his death, Sean O’Casey paid tribute to ‘Big Jim’ in the pages of the national media, where he was quoted as saying:

It is hard to believe that this great man is dead; that this lion of the Irish Labour movement will roar no more. When it seemed that every man’s hand was against him the time he led workers through the tremendous days of 1913 he wrested tribute of Ireland’s greatest and most prominent men.

O’Casey noted that Larkin was far and away above the orthodox labour leader, “for he combined within himself the imagination of the artist, with the fire and determination of a leader of the downtrodden class.”

To deny that Larkin was an at-times difficult character is to deny the truth, and many biographies of Larkin give insight into what was at times a dangerously sharp tongue and what historian Emmet O’Connor perfectly described in his biography of Jim as a “brash personality.” His clashes with others in the union movement like William O’Brien on occasion quite literally divided the movement, yet he remains the most inspirational figure to arise from the pages of Irish labour history, on par with the Edinburgh born James Connolly.

Larkin’s funeral arrangements, as reported in major newspapers on the day of the funeral.

The funeral of the Liverpool born agitator brought thousands of Dubliners onto the street. The removal alone witnessed thousands coming out to see the body removed to St Mary’s Church, draped in the Plough and the Stars, the flag of the Irish Citizen Army of which Larkin had been a founding member. Prior to this the body had been at Thomas Ashe Hall, and The Irish Times noted that “the guard of honour who kept watch beside the coffin throughout Saturday were drawn from members of the Irish Citizen Army and veterans of the 1913 labour struggle.” Among the messages of sympathy received was one from Archbishop McQuaid, along with others from the international trade union movement. George Bernard Shaw told the media that “we all have to go. He done many a good days work.”

Thousands lined the route of the funeral procession from St Mary’s Church to Glasnevin Cemetery, and the scale of the turnout is obvious from reports, which noted for example that at Liberty Hall 1,200 Dublin dockers formed a guard of honour. The mass itself had been celebrated by John Charles McQuaid, and John Cooney notes in his biography of McQuaid that “while the poor poured out their grief at Larkin’s death, McQuaid thanked God that the man long feared as the anti-Christ had died with Rosary beads wrapped around his hands. Larkin’s pious death was McQuaid’s most treasured conversion.”

At Glasnevin Cemetery the oration was delivered by William Norton, Labour T.D. Norton told the crowd that: “If each of us here would resolve to reunite our movement, to eliminate the bickering, the pettiness and the trivialities which divide and impede us, our success in achieving a united movement is assured.” It was not until 1990 that SIPTU was formed from a merger of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union and the Federated Workers’ Union of Ireland.

Multitext, UCC’s remarkable online project in Irish history, contains fantastic images of Larkin’s removal and funeral. We have reproduced them below. Larkin remains a giant of Dublin history and the story of the Irish working class, and he should be remembered with pride on this year in particular, which marks the centenary of the 1913 dispute.

The funeral cortege of Jim Larkin. Via http://multitext.ucc.ie

Posted in Dublin History | 7 Comments »

On Wednesday 23 January, RTE’s Nationwide programme had a special feature on the Jewish community in Dublin. It can be watched, anytime over the next sixteen days, on the RTE Player here.

It includes:

– Elaine Brown and her daughter Melaine taking Mary Kennedy on a tour of Clanbrassil Street and helping to identify Jewish shops from a 1965 RTE documentary.

– A feature on the originally Jewish Bretzel Bakery (estd. 1870) in Portobello which has had its Kosher status re-established since William Despard and Cormac Keenan took over in 2000. Also includes interview with Cantor Shulman whose job is to inspect the bakery and make sure it is following the Kosher rules.

– Detailed story of Ettie Steinberg, the only Irish born victim of the Holocaust. She grew up on Raymond Terrace off the South Circular Road and was educated in St. Catherine’s School on Donore Avenue. Ettie was murdered with her German husband in Auschwitz. Includes interviews with Dubliner and Irish-Jewish genealogist Stuart Rosenblatt and Yvonne Altman O’Connor of the Irish Jewish Museum

Posted in Dublin History | 4 Comments »

Lord Edward Fitzgerald is one of the most romantic figures in Irish history, a rebel aristocrat associated with the failed revolution of 1798, known as the ‘Citizen Lord’. He is today buried in Saint Werburgh’s Church near to Dublin Castle, an institution he hoped to overthrow by force. A small plaque on the front of the church marks this fact, and it’s one of the great ironies of the city that Major Henry C. Sirr who captured him is buried in the graveyard at the back of the church.

One figure associated with Edward Fitzgerald I’ve been fascinated by for a while now is Tony Small, an escaped slave Fitzgerald encountered in the United States who he later employed as a personal assistant. Small became a frequent sight around Dublin in the 1780s and 1790s, in a city where coloured men were few and far between. Fitzgerald commissioned a portrait of Small in 1786 by the artist Thomas Roberts:

In her brilliant biography of Fitzgerald, Stella Tillyard noted that “If Lord Edward’s mother was his great love, his constant companion was Tony Small, the runaway slave who saved his life in North America in 1781”, and she went on to note that “Tony embodied and brought to life his master’s commitment to freedom and equality for all men.”

Small had witnessed the British and Americans at war firsthand in 1781, as when his owners had fled South Carolina with their possessions and slaves, Tony had escaped and stayed on. On the 8th September 1781, Tony wandered onto a battlefield, and as Tillyard has noted he stumbled across “the blood-soaked uniform of a British officer of the 19th Regiment of Foot. The man was alive but unconscious, overlooked by the search parties of both sides.” The man was Edward Fitzgerald, and when he next awoke he was in the small hut Tony Small knew as his home. Fitzgerald offered Small liberty, and a new life working as his servant, in return for wages. An incredible and unlikely friendship had been born.

Kevin Whelan discusses the friendship between the two in his entry on Lord Edward Fitzgerald for the Dictionary of Irish Biography, noting that “The best-documented Irish example of imaginative sympathy between a white and a black man is the subsequent relationship between Fitzgerald and Small. Until his death in 1798, in a sprawling career that took him across much of Europe, America, and Canada, Fitzgerald never subsequently parted from his ‘faithful Tony’.”

In time, this one-time British soldier and darling of the Ascendancy class was converted towards the ideas of republicanism, the influence of writers such as Thomas Paine and personal observation on the streets of France inspiring this total shift in identity and politics. It was not until 1796 that Fitzgerald joined the United Irishmen, but the seeds had long been planted.

Posted in Dublin History | 17 Comments »

William Graham was a 23-year-old Dubliner and member of the anti-Treaty IRA when he was shot dead by the Free State Army in November 1922 at Leeson Street Bridge. There is no plaque or monument to mark the spot of his incident.

William was born in 1900 to William Sr. and Mary Graham, both originally from Wexford. The 1901 census shows that the family were living at 5.3 Cornmarket, the road that links High Street (by St. Audoen’s Church) and Thomas Street. William Sr (43) was a Stationery Engine Driver while his wife Mary (39) looked after their four sons and three daughters. All were Roman Catholic. Myles (15) was a messenger at the GPO and Alice (14) was an apprentice in a shirt factory. John (10), Katie (7), James (5) and Bridget (3) were at school while young William (1) was only a baby.

Ten years later the family had moved around the corner to 4.5 Ross Road, part of the Corporation Buildings. This road connects High Street with Winetavern Street.

The 1911 census tells us William Sr. had died sometime during the last decade. He left his widow Mary (50) along with his children Alice (26), a Cake Packer, John (20), a Van Driver, Cathrine/Katie (17), no occupation listed, and James (15), a Telegraph Messenger. Myles had left the family home by this stage. Bridget (13) and William (11) were both at school. Denis Lennon (54), an illterate single man from Wexford listed as Mary’s brother in law, also lived with the family.

At the time of his death in 1922, William Graham was listed as living at 4 Ross Road which corresponds with the census records. Interestingly, 4 Ross Road is the address given by two insurgents who were arrested after the Easter Rising in 1916. These were Peter Kavanagh, a plumber’s assistant, and Patrick Kavanagh, a fitter’s assistant. The 1911 census shows that there were two Kavanagh families living in the Ross Road Corporation Buildings, however, only one matches the above names.

‘Cristíona Ní Fhearghaill bean Seáin Uí Caomhánaigh’ which translates as ‘Christina Farrell, wife of John Kavanagh’ was living at 2.2 Ross Road in 1911 with her three sons and two daughters – Máire (22), Peadar (16), Padraig (13), Samuel (10) and Cáitlín (7). Mary were listed as working as a ‘bean fuaghala’ (seamstress) while Peter is down as a ‘buachaill oiffige’ (office boy). Patrick, Samuel and Kathleen were at school.

Irish Volunteer William Christian from Inchicore recorded in his witness statement that:

On Easter Monday I was mobilised by Peter Kavanagh. He was then living in Ross Road and he desired me to pass on the news to any of the other volunteers who might be perhaps living in the neighborhood. I knew of nobody save my pal, James Daly, so I called fro him and both of us proceeded to Earlsfort Terrace…” (BMH WS 646)

IRA officer Seamus Kavanagh from Clanbrassil Street records in his Witness Statement (No. 1053) that Peader Kavanagh was a member of ‘C’ Company who fought in Bolands Bakery. It is not known where Padraig fought.

It is interesting that the two Kavanagh brothers, living at 2 Ross Road in 1911, would give their address as 4 Ross Road after the Rising in 1916. While I can’t find any evidence that the 16 year old William Graham played any role in the Rising, there is no doubt that he would have been politicalised by the event and, in particular, the arrests of his two neighbors. Or perhaps they were actually living with the Graham family in 1916?

The only reference that I can find of Graham in the Witness Statements from Stephen Keys who was Section Commander of ‘A’ Company, 3rd Batt. Dublin Brigade IRA from 1918-23. Quite bizarrely, he calls him ‘Kruger Graham’ and I haven’t yet been able to find out why. (Kruger seems to be a name associated with South Africa)

Stephen Keys gives a first hand account of the events, that himself and Graham were involved in during the winter of 1922, leading up to his death:

At the next attempt to blow up Oriel House, my job was to take away the men and cover the retreat … I commandeered a car from Leeson St. I was not able to crank the motor and I always had to leave the engines running. The mine went off with such force that you would be blown off your feet … The lads ran by … The last to come was Kruger Graham … (he) jumped into the back of the car and said, “Drive Steve. They are all out. I am the last”

Oriel House, at the intersection of Westland Row and Fenian Street, was the HQ of the feared and hated Free State Intelligence Department. Today, it is owned by TCD and is the headquarters for CTVR, The Telecommunications Research Centre.

Stephen Keys goes on to say that after the aformentioned attempt on Oriel House, their next engagement was “…sticking up an armed guard at Harcourt St. railway.”. He describes this as “a battalion job (with) mostly ‘A’ Company men” involved. We can come to the conclusion that William Greham was a member of the 3rd Batt. of the IRA and quite possibly ‘A’ Company.

Keys writes:

I had another car on this occasion, an open car. They were to bring down the rifles from the railway and load them into the car. Willie Rower was on this job and he shot someone, which disorganised the plan and spoiled the job. I drove around, thinking I would pick up some men who might be straggling around the place.

The Irish Independent of 28 November 1922 wrote that a Lt. Comdt. of the Free State Army was “on duty in the vicinity of Harcourt St … with 3 whippet cars and a tender (when) shortly after 9pm … he heard shooting.”. This patrol rushed to Harcourt Station and found one of the guards there had been disarmed.

After finding out what had happened, he collected his men and proceeded along Hatch Street to Leeson Street. Here, three men were spotted by the bridge. The Free State soldiers called on them to halt. Searching the trio, they found nothing on the first man but they discovered that Graham had a fully loaded Webley revolver tucked down his trousers.

This is when the story diverges slightly.

Posted in Dublin History | 9 Comments »

Isolde’s Tower on Exchange Street Lower was discovered in 1993, during work on the renovation of the Temple Bar area. During excavations on the site of five demolished Georgian houses, archaeologists found the base of the Tower, which served as the north-east corner tower of the 13th century city wall of Dublin. Prior to the demolition of the Georgian houses, they had been occupied for a period by a group calling itself the Society against the Destruction of Dublin, joined by Green Party Councillor Ciaran Cuffe. The find below the Georgian homes sparked huge media interest, and it was estimated by historians and archaeologists that the tower had once stood at 30-40ft, prior to being demolished sometime in the 17th century.

The firm of architects responsible for demolishing the Georgian houses and building apartment blocks in the location, Gilroy and McMahon, promised to incorporate the archaeologists findings into their project. This fantastic video from the Dublin City Walls App gives some idea of how the incredible tower may have appeared.

True to their word, the remains of the tower were incorporated into the apartment complex of the same name. However one of my pet hates about this part of town is the manner in which they are almost always covered up by bins connected to the complex, as this image shows. It seems a real pity that such a gem of an archaeological find is blocked from view.

Posted in Dublin History | 5 Comments »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.