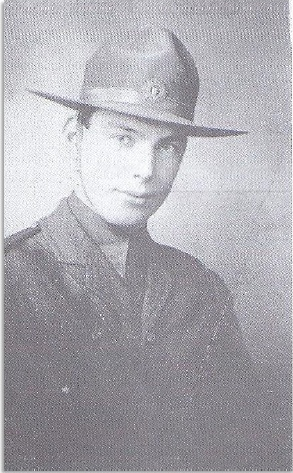

Last Sunday, nine of us made the trek from the car park of Montpelier Hill to the Captain Noel Lemmas memorial deep in the Dublin Mountains. While Ciaran is due to post up some pictures from this memorable journey, I thought it would be no harm to talk a little about Captain Noel Lemass and his isolated monument

Captain Noel Lemass (1897-1923) of the 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade IRA fought in the General Post Office (GPO) during the Easter Rising of 1916, took an active part in the War of Independence (1919-1921) and joined the occupation of the Four Courts after taking the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. His younger brother Sean, who had a similar military career, would go on to become Ireland’s fourth Taoiseach.

After the fall of the Four Courts, Noel was imprisoned but managed to escape and make his way to England. He returned to Ireland during the summer of 1923 when the ceasefire was declared. Returning to work at Dublin Corporation, he asked the town clerk John J. Murphy if he would forward a letter to the authorities that he planned to write “stating that he had no intention of armed resistance to the Government”. (1)

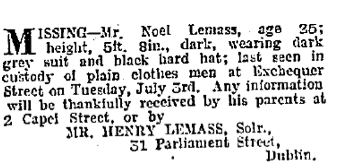

In July 1923, two months after the Civil War ended, Noel was kidnapped in broad daylight by Free State agents outside MacNeils Hardware shop, at the corner of Exchequer and Drury Street.

Three months later, on 13th October, his mutilated body was found on the Featherbed Mountain twenty yards from the Glencree Road, in an area known locally as ‘The Shoots’. It was likely that he was killed elsewhere and dumped at this spot.

The Leitrim Observer of 20 October 1923 described that Civic Guards found his body:

clothed in a dark tweed suit, light shirt, silk socks, spats and a knitted tie. The pockets contained a Rosary beads, a watch-glass, a rimless glass, a tobacco pouch and an empty cigarette case. The trousers’ pockets were turned inside out, as if they had been rifled. There was what appeared to be an entrance bullet wound on the left temple, and the top of the skull was broken, suggesting an exit wound.

Noel was shot at least three times in the head and his left arm was fractured. His right foot was never found.

Meeting two days later, Dublin Council passed a strongly worded vote of sympathy with his family. Describing their fellow employee as an “esteemed and worthy officer of the Council who had been foully and diabolically murdered”, the Council adjourned for one week as a mark or respect. (2)

It was believed that many that a Free Stater Captain James Murray was behind the murder.

His funeral was described by The Irish Times on 17 October 1923 as “ranking with some of the largest seen in the city in recent years”. The hearse was preceded by the Connolly Pipers’ Band and followed by members of the Cumann na mBan, Women’s Citizens Army, Sinn Fein Clubs, Prisoners’ Defence League, many recently released prisoners, representatives of various bodies and numerous well-known Republicans including George Noble Plunkett (father of Joseph Plunkett), Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne.

Noel Lemass in uniform. Credit – http://irishvolunteers.org

A year later, a memorial cross was erected at the spot where his body was found.

MJ Freeney, on a hill walking trip, wrote in the Sunday Independent on 24 July 1927:

Our road wound to the right and soon we a met sharp turn on our left. Having negotiated this, we found ourselves on the wild Featherbed Pass. Civilisation had been left far behind. Our only companions were rough mountain sheep and strange wild birds. Truly no lonelier spit could be found. And then a glance to our left. There in the wilderness was a cross. What strange object in such a place. We read the name – Captain Noel Lemass

The Irish Times of 12 September 1932 reported on the “first public commemoration” of the late Captain Noel Lemass which saw:

Omnibuses and motor cars .. (bring) hundreds to the scene, whilst still greater numbers made the journey on foot

The Chairman of the Noel Lemass Cumann of Fianna Fail (Mansion House Ward), George White, laid a wreath at the foot of the cross while The Last Post was sounded by Owen Somers. Joseph O’Connor of the 3rd Battalion delivered the oration:

Noel Lemass… joined the movement in 1916 and was wounded in O’Connell Street in that year, and in 1917 he assisted in reforming the organisation and served in it right up to the time of his death .. He was one of the typical young men in the Republican movement, animated by one great motive – the desire for freedom

In 1932, Sean Leamass (then Minister for Trade and Commerce) led the pilgrimage to the monument. Four years later, several hundred people traveled by bus and motor car to the ‘sequestered spot in the Dublin Mountains’ where the body of Noel Lemass was found.

As far as I can work out, there were annual pilgrimages to the spot in Featherfed mountain from 1932 until at least 1977.

Every year saw hundreds descend on the remote spot to pay their respects.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.