A brief look at the attempts to bring Wimbledon F.C to Dublin in the 1990s.

Wimbledon F.C

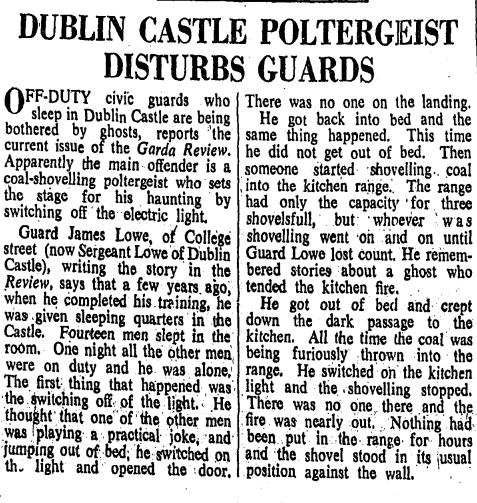

One of the most interesting disputes in the history of ‘The Beautiful Game’ in Dublin was undoubtedly that around proposals to bring Wimbledon to Dublin in the 1990s. Backed by a number of high-profile supporters, a consortium attempted to move the team here and rebrand them as the ‘Dublin Dons’. This caused considerable anger among fans of the domestic league, and the issue featured heavily in the mainstream media.

Wimbledon Football Club spent much of their football history at Plough Lane, an old-fashioned football stadium in Wimbledon, south-west London. Wimbledon had played in the ground since September 1912, but by the 1990s the ground was lagging behind and did not meet the required standards. Crystal Palace would become the landlords of Wimbledon, as the club groundshared at Selhurst Park for a period.

Among those who backed the campaign to bring Wimbledon to Dublin were Eamon Dunphy and Paul McGuinness, manager of U2. The developer Owen O’Callaghan and Dunphy were instrumental to the plan, as the hope was for Wimbledon to play their games at a stadium O’Callaghan planned to construct in West Dublin. This stadium, located in Neilstown, was intended to hold an impressive 40,000 seats. The first meetings between O’Callaghan and the owners of Wimbledon Football Club occurred in April 1996.

When O’Callaghan first met with Sam and Ned Hammam, owners of the football club, he was joined by Dunphy and McGuinness. O’Callaghan and the consortium who wished to bring Wimbledon here found common ground and interest on the matter through O’Callaghan’s planned Neilstown stadium. The prohibitive costs of that venture, coupled with a belief it would not be used to its full potential, meant that it was seen as an ideal ‘home’ for Wimbledon to relocate to. In April 1996 it was reported the consortium were urging O’Callaghan to begin quick construction on this ground, in the hope it could be completed by the 1998 football season. Among those who backed the plan to create the ‘Dublin Dons’ was the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, who in August 1996 publicly proclaimed that English Premiership football could bring huge economic benefits to Dublin.

With the domestic game, Damien Richardson was one of the few who backed the planned move to Dublin, noting that “I feel their presence here would raise the profile of the sport in Ireland and the League would benefit”, while Brian Kerr took the opposite view, believing such a move would be devastating for the domestic game, already competing with English soccer for media coverage.

Plough Lane, the historic home of the club. (Wiki)

Opposition to the planned move from lovers of the domestic game was strong. Around 200 supporters packed into Wynn’s Hotel for a meeting in September 1996. At that meeting, Niall Fitzmaurice announced that the arrival of the “Wimbledon Dons” would mean the “death of the National League within five years”, and he went on to state that those behind the proposal had purely financial motivations claiming “they have no love for the game.”

Protesting Wimbledon fans (Irish Independent, Dec. 8 1997)

The idea of moving Wimbledon to Dublin naturally upset many supporters of the club, with scenes of protest inside and outside their matches at Selhurst Park in 1997. In December of that year,Sam Hammam responded to a demonstration by Wimbledon fans following a one-nil win over Southhampton by telling the media he would “probably do the same thing” if he was a fan, but insisting that “Dublin is a fantastically sexy option, what else can I say?” Hammam even claimed that had he wanted it, he could have had the club in Dublin already, insisting that “the only reason we aren’t there is that I’ve chosen not to do it.”

A 1998 poll carried out by Lansdowne Market Research for the Irish Independent claimed that two out of three Irish adults interested in the game of football were in favour of Wimbledon moving to Dublin, but the F.A.I were among the most vocal critics of the idea, with the then Chief Executive Bernard O’Byrne insisting to the paper that all F.A.I surveys within the Irish football community told a very different story in terms of support for the proposed move.

In a brief piece on the Dublin Dons, soccer-ireland notes that:

The cost of the Dublin Dons project was estimated at £100 million (€127 million) including the stadium construction, road, rail and security infrastructure, £5 million for the FAI, £5 million for the League of Ireland clubs, and the provision of a number of football schools of excellence around Ireland.

Ultimately, the opposition of the F.A.I would prove crucial to preventing the move, with Bernard O’Byrne outlining the Associations opposition to the move in a five-page letter sent to the chairmen of every Premiership club in 1998 for example. Likewise, UEFA and FIFA opposed the idea, which proved a crippling blow. Interestingly, in one media interview Bernard O’Byrne mentioned the infamous Lansdowne Road riots of 1995 and asked “do people want 5,000 English football fans every fortnight in Dublin?”. Wimbledon were eventually moved to Milton Keynes, against the wishes of many of their supporters. This new relocation, while keeping the club in England, still ripped the club from its historic heartland. The club fell into financial crisis, and in 2004 was totally rebranded as MK Dons F.C. Out of opposition to the clubs relocation, some fans set about establishing AFC Wimbledon, who currently play in League Two of the Football League in England.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.