Earlier this week, the statue of Molly Malone was added to the Talking Statues series, an innovative and playful idea that allows Dubliners and visitors to engage with monuments in the city. Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw and James Connolly (albeit without Edinburgh brogue) are just some of the monuments that are brought to life by the series. This summer is the thirtieth anniversary of the unveiling of the famous Dublin statue of Molly Malone,making her an ideal candidate for inclusion.

Molly Malone by Jeanne Rynhart took her place on the Dublin streetscape in 1988, the year of Dublin’s so-called Millennium. The historical merit of 1988 as a Millennium date for Dublin was widely disputed, but the year did lead to much civic pride and engagement. When quizzed on this, a Dublin Corporation official came out with something that was almost Flann O’Brienesque, insisting that when it came to historians, “you can never get these people to agree anyway. After all, there are some who say St Patrick never existed, but that doesn’t get rid of March 17th. And who picked December 25th as Christ’s birthday? Nobody was sure what the real day was, so they had to pick something.”

Rynhart’s proposal emerged victorious from dozens of entries, and was unveiled in December 1988 right at the end of the year of celebrations. When first revealed, the Irish Independent reported that “men reacted favorably to the buxom, six-foot Molly…wearing a low-cut, off the shoulder period dress, her hair immaculately braided.” In the eyes of one journalist, the monument had “more curves than a seventeenth century road through the Liberties.” In defending her work, Rynhart noted that Molly’s outfit was based on discussions with costume experts from the National Museum of Ireland, and that “breasts would not have shocked seventeenth century Dubliners.”

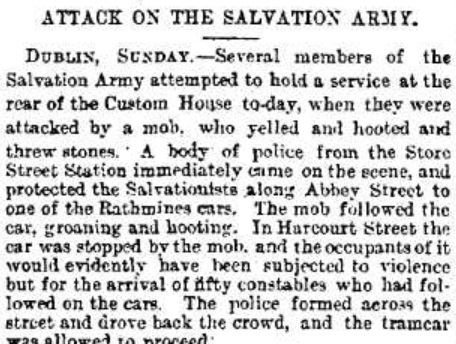

Rynhart defending Molly Malone, Irish Press.

Whatever about the criticisms of Molly’s appearance, the greatest criticism of the work came from the Independent Socialist politician Tony Gregory, who maintained that the monument was on the wrong side of the Liffey and should have been placed in a “place of historical relevance.” Still today, it seems peculiar Molly Malone – a fictional street trader – stands so far from the traders of Moore Street.

While Aosdana lamented the statue as being “entirely deficient in artistic point and merit” at the time of its unveiling, I am personally a great admirer of Rynhart’s Molly Malone. A strong mythology grew up around Molly Malone in 1988, when an attempt was made to sell the idea that she was based on a genuine seventeenth century fishmonger/prostitute (the 13 June was declared ‘Molly Malone Day’ in honour of a woman who had died on that date in 1699). There was no need for it. To me, Molly Malone is not one woman from history, but a representation of women workers in a Dublin long gone. As for her location, I’m with the late Tony Gregory on that one.

Equally controversial was the Anna Livia fountain placed on O’Connell Street, which was quickly descended on by Fairy Liquid bandits who knocked great enjoyment out of watching suds spill over onto the street. Today, Anna Livia (the work of sculptor Éamonn O’Doherty) sits in the small public park at Wolfe Tone Quay, near to the National Museum of Ireland. Smaller acts, like the planting of hundreds of new trees in the city centre, also changed the appearance of the city centre in a meaningful way too during the doubtful Millennium.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.