There have been numerous excellent books produced on the Irish Republican and Socialist movements in the 1930s. The below is a brief post on two days of interesting Anti-Communist violence in April 1936, when the Left was attacked firstly on a broad republican march to Glasnevin Cemetery, and then the following day at a rally on College Green. It is intended as a brief insight into Anti-Communism in Dublin in the 1930s.

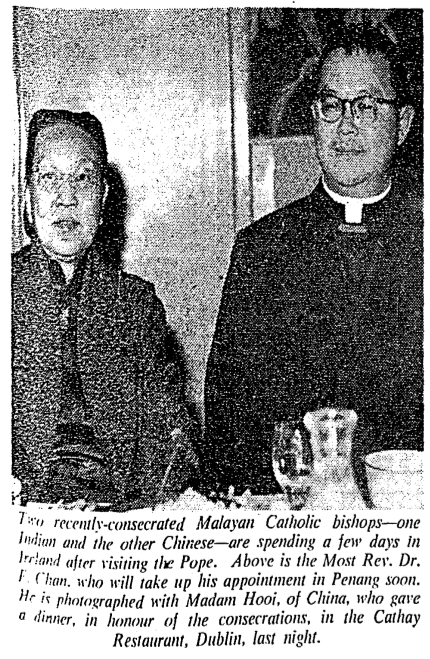

Willie Gallacher, a Scottish Communist MP present on the March to Glasnevin on April 12th 1936 and who was to speak at College Green the following day.

On 12th April 1936 Communists and left Republicans attending an Easter commemoration at Glasnevin Cemetery came under attack at various points along the route to Glasnevin from the city centre, during an event which was plagued by violence. It was not the last anti-Communist violence in April 1936, and just who was responsible for the violence was unclear, though the left-wing Republican Congress laid the blame at the feet of the far-right, the ‘Animal Gang’ and “other such defenders and faith and morals”.

The procession marched from the Carmelite Church on Whitefriars’ Street, following a mass for the requiem of the souls of fallen comrades, and made its way for Glasnevin. Within the sizeable procession was a contingent of a few dozen members of the Communist Party, who the Irish Press noted “wore red tabs attached to Easter Lillies.” Led by Sean Murray and Captain Jack White (a founding member of the Irish Citizen Army), this contingent included Willie Gallacher, the Scottish Communist M.P. In addition to the Communist Party, members of the Republican Congress marched in the procession. There were five bands in total in the march, and all shades of Republican opinion were represented.

The Communist contingent in the march, though small in the context of the demonstration, came under attack firstly on Westmoreland Street when about 20 people attempted to rush the crowd, and, newspapers reported by the time O’Connell Bridge had been reached a sizeable crowd were shouting “We want no Communists in Ireland!” at their targets. By the General Post Office, the attacking crowd was said to number 200 people, and police were forced to draw their batons. A hostile crowd tailed the Communists all the way to Glasnevin, and some leading left-wing activists of the day sustained injuries, with George Gilmore receiving nasty wounds as a result of the crowds stone throwing.

The Irish Independent reported that on reaching Glasnevin, the shout was raised that “this is a Catholic grave yard. Don’t let the Communists in!” The great irony of Glasnevin being non-denominational was lost on someone! Outside, sellers of the English Communist paper the Daily Worker found themselves attacked by the hostile crowd. In a letter to the Irish Press days after the violence, one member of the public noted that while such violence was unfortunate, it was the natural outcome of an attempt to stage an “anti-God display” at Glasnevin.

Patrick Byrne, a leading activist with the Republican Congress, recalled years later that:

The main target of the mob was Captain Jack White. He had been injured with a blow of an iron cross wrenched from a grave. It was necessary to get him away quickly. Fortunately, the Rosary had started and this caused a lull during which Tom O’Brien and myself got him away. Captain White wrote afterwards: “By the aid of two Republican Congress comrades, who knew the geography, we left by an inconspicuous back door. Slipping under a barbed wire fence, the Congress comrades and I dropped on to the railway and soon emerged into safety and a Glasnevin tram.”

Newspaper report on the chaos described below at College Green.

The following day, on the 13th April, a left-wing meeting at College Green came under siege when thousands gathered for a rally featuring speakers from the left including Peadar O’Donnell and Willie Gallacher. Garda reports estimated that the crowd numbered between four and five thousand. They estimated that 98% of this crowd were hostile to the left-wing speakers at College Green. Prior to this meeting even beginning, newspaper reports noted that Gardaí lined College Green 100 strong. Peadar O’Donnell would be the only speaker on the night, addressing the crowd from a lamppost. In an obituary printed at the time of O’Donnell’s passing at the fine old age of 93, it was claimed that O’Donnell was met by “potatoes (with razor blades embedded in them), bottles and stones.”

Historian Fearghal McGarry has noted that following this event an anti-Communist mob laid siege to targets in the city centre, attacking the offices of the left wing Republican Congress and also attempting to attack other buildings associated with the left, although police prevented this. Interestingly, McGarry notes that targets included Trinity College Dublin and the Masonic Hall, and this indicates a spirit of militant Catholicism among the crowd.

Peadar O’Donnell would later comment that

After all it wasn’t the tycoons of Dublin who tried to lynch me in College Green during a Red Scare but poor folk who had been driven out of their minds by a month’s rabid Lenten Lectures.

Continue Reading »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.