Joseph Nannetti, Lord Mayor of Dublin 1906/7.

Little Jerusalem has a special place in the folk memory of Dublin, with the area around Portobello and the South Circular Road boasting a number of plaques and a museum which tells the story of Jewish Ireland. The story of Jewish Dublin includes names like Harry Kernoff, Leopold Bloom, Leslie Daiken and Chaim Herzog, and has been documented in memoirs like Dublin’s Little Jerusalem by Nick Harris.

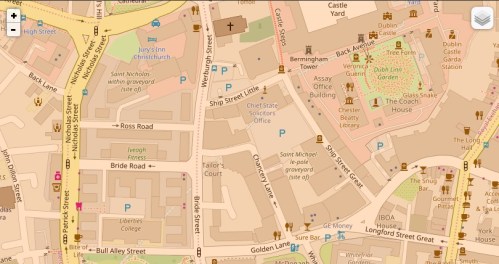

One of the more curious migrant quarters that has all but disappeared from memory is Little Italy, located in the vicinity of Little Ship Street, Chancery Lane and Werburgh Street. Its story is intertwined with that of the Cervi family, who established a lodging house in the area which became popular with Italian workers in the city. In the words of Toni Cervi, son of Guisseupi Cervi (who opened Dublin’s first fish and chip shop in 1882):

The area around us – off St. Werburgh Street….was known as ‘Little Italy’. If someone came to Dublin and wanted to locate a particular Italian, he would more often than not be directed to Little Italy. The place was filled with barrel-organ men, ice-cream men who traveled the city with their barrows, and with marble men.

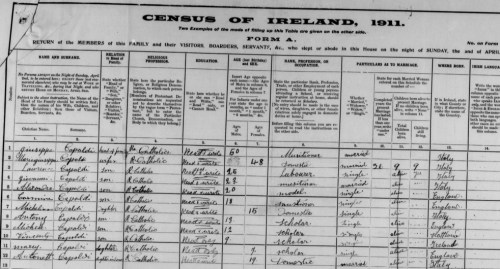

The 1911 Census returns of the Capoldi family, living in Chancery Lane. Notice the diversity of birthplaces, revealing the journey the family had undertaken before setting in Dublin (National Archives of Ireland.)

Little Italy never amounted to a community the size of Little Jerusalem. As Cormac Ó Grada has noted, Dublin by 1912 contained fewer than 400 migrants of Italian stock. What is telling was the diversity of Italian migrants living in Ireland in terms of skilled labour; workers from Italy’s Lucca region tended to be “made up of artisans, plaster workers, and woodworkers, with surnames like Bassi, Corrieri, Deghini, Giuliani and Nanetti.” Others, originating in the Val di Comino, tended to be “either street-sellers of ice cream or cafe owners.” The later included familiar names like Forte and Fuscos.

References to Dublin’s ‘Italian Colony’, as such quarters were known, are plentiful in the press of the 1880s and 1890s. The Freeman’s Journal wrote in 1886 of the contribution of Italians living in Dublin to New Years Eve traditional festivities:

There is within the boundaries of Dublin no more extraordinary spectacle to be witnessed on New Years Eve than the annual serenade of the Italian organ-grinders and musicians in Chancery Lane. This comparatively unknown portion of the city has been for many years the headquarters of all the Italian and other itinerant foreign street musicians who migrate to Dublin.

Italian ice cream men sometimes got a hard time of it in the Irish press, with the Evening Herald lamenting how “thoughtless city children eagerly partake of the ice-creams vended by them. These delicacies are manufactured and stored in the tenements of Chancery Lane…It should interest the authorities to discover whether these dairies are registered according to law.” Still, Dubs trusted the Italians when it came to ice cream. John Simpson has noted that “the 1901 Ireland census records the Dubliners’ indebtedness to their compatriot Italians for ice-cream. Of 23 people listed as involved with the ice-cream trade as vendors or makers, all but seven were born in Italy.”

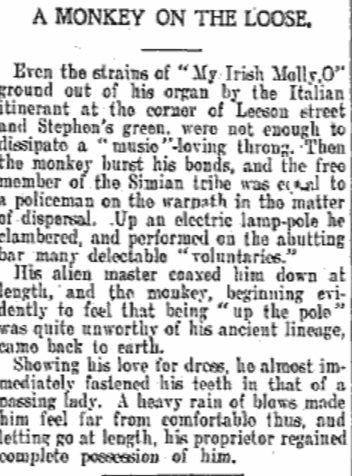

Italian organ grinders, complete with performing monkeys, became familiar sights on the streets of the capital too. The occasional escaping money made it into the press, and sometimes their owners made it into the courts.

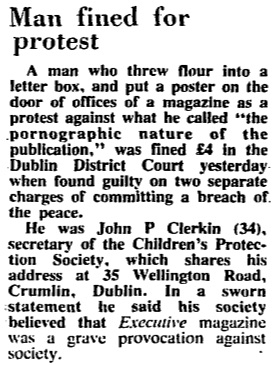

Irish Independent, March 1906.

The most well-known figure to emerge from the Italian community in Irish public life was Joseph Nannetti, the son of an Italian sculptor and modeller who involved himself in both municipal and national politics. A Home Rule nationalist and a committed trade unionist (though of a school of trade unionism that was very different from the radicalism preached by men like Connolly and Larkin), Nannetti served as Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1906/7, and is mentioned by James Joyce within the pages of Ulysses.

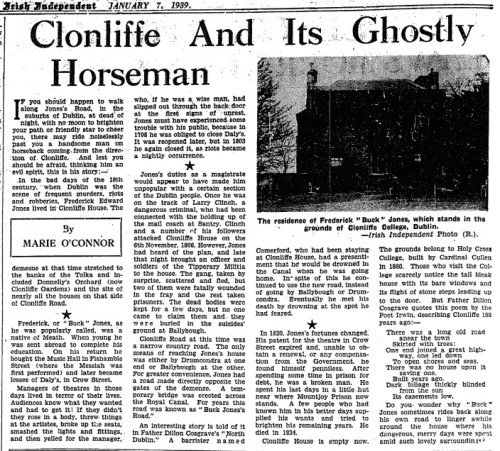

The level involvement of Italians in radical Irish politics is difficult to gauge, though there are some passing references to the Irish Italian community within the Bureau of Military History. Stephen Keys,a section commander in the IRA’s Dublin Brigade during the War of Independence, remembered that “No one in Camden Street ever attempted to obstruct us.. In fact, they had great respect for us. Some of the shopkeepers; in that area, including an Italian named Macetti who had an ice-cream shop, used to subscribe to our arms fund.” There are mentions of some members of the Italian community in Belfast suffering during the Anti-Catholic pogroms there in the dark days of the Civil War too.

One family of Italian blood who were deeply involved with republicanism during the revolutionary period were the Corri’s, with Hayden Corri’s Military Service Pension file detailing his contribution to the Republican Police during the War of Independence and the Republican side of the Civil War. Hayden and his brother, WIlliam Corri, were the grandchildren of the talented landscape painter Valentine Corri, whose family hailed from Rome.

Contemporary Ordinance Survey map showing some of the streets where Dublin’s Italian community settled, including Ship Street Little and Chancery Lane (Image Credit: OSI)

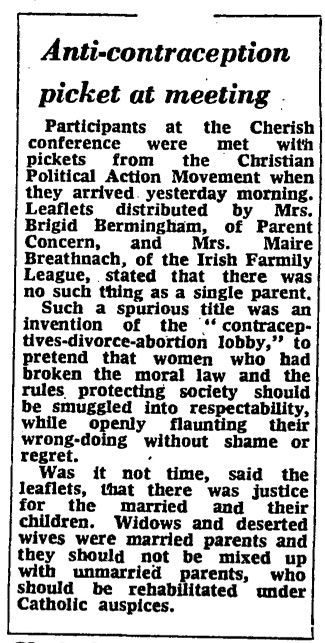

With the emergence of Fascism in Italy, the ideology gained influence among some sections of the Italian community in Ireland. The presence of Italian ‘Fascisti’ in Dublin was closely monitored by state intelligence. The fourth anniversary of Mussolini’s March on Rome was marked at the Italian Consul’s Office on Lower Abbey Street, while an ‘Irish Free State Fascisti Headquarters’ was opened at Fownes Street in September 1927. At the funeral of Kevin O’Higgins, the government minister assassinated by Irish republicans in retaliation for the execution policy of the Free State in the Civil War, the Leinster Leader newspaper reported that “a picturesque note was struck by the Dublin Fascisti in blackshirts.”

Evening Herald, October 1926.

There is no trace of Italian migration in the areas around Chancery Lane, Werburgh Street and Little Ship Street today. Familiar Italian names over fish and chip shops, and beautiful stucco work inside some of Dublin’s finest homes, remain however.

My grá for Herbert Simms is well known. Dublin’s Housing Architect from 1932 until 1948, this year marks the 120th anniversary of his birth, as well as the 70th anniversary of his tragic suicide. We have previously examined Simms

My grá for Herbert Simms is well known. Dublin’s Housing Architect from 1932 until 1948, this year marks the 120th anniversary of his birth, as well as the 70th anniversary of his tragic suicide. We have previously examined Simms

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.