The Turkish Baths of 1860, Lincoln Place, Dublin. Our story today concerns an early forerunner of these Turkish Baths. (Image: Archiseek)

In the Dublin of the late eighteenth century, Achmet Borumborad cut an unusual shape. A tall Turkish man sporting a fine beard and wearing traditional Turkish attire, Jonah Barrington (judge, lawyer and Dublin socialite) remembered him as “being extremely handsome without any approach to the tawdry, and crowned with an immense turban, he drew the eyes of every passersby; I must say that I have never myself seen a more stately-looking Turk since that period.”

Borbumborad was literally followed through the streets of the capital by the curious, with Barrington relating how “the eccentricity of the doctor’s appearance was, indeed, as will be readily be imagined, the occasion of much idle observation and conjecture. At first, wherever he went,a crowd of people, chiefly boys,was sure to attend him, but at a respectful distance”.

A doctor by profession with immaculate English, Borbumboard quickly made his way into the upper echelons of Dublin society, wining and dining with the elite of the College Green Parliament, gaining a reputation as a fine conversationalist who was “pregnant with anecdote, but discreet in its expenditure.” He is mentioned in contemporary publications, with a poem entitled The Medical Review from 1775 describing “his foreign accent, head close-shaved or sheard. His flowing whiskers, and great length of beard.”

While the period calls to mind the privileged dueling ‘Bucks’ of Trinity College, sedan chairs on College Green and the occasional riot in the Smock Alley Theatre, eighteenth century Dublin had its fair share of poverty and misery too, evident from primary sources like the survey census of the city carried out by the Reverend James Whitelaw in the summer of discontent that was 1798. Whitelaw was horrified to report:

I have frequently surprised from ten to 16 persons, of all ages and sexes, in a room, not 15 feet square, stretched on a wad of filthy straw, swarming with vermin, and without any covering, save the wretched rags that constituted their wearing apparel. Under such circumstances, it is not extraordinary, that I should have frequently found from 30 to 50 individuals in a house.

While groundbreaking work on the infectious nature of disease (such as that carried out by Oscar Wilde’s father, Sir William Wilde) remained a long way off in the distance, many contemporary observers in the eighteenth century were aware of the poor health of the less well-off inhabitants of Dublin. Borbumborad, the man from God knows where, was among such voices. Barrington recounts how “he proposed to establish what was greatly wanted at that time in the Irish metropolis, ‘Hot and Cold Sea-water Baths’, and by way of advancing his pretensions to public encouragement, offered to open free baths for the poor on an extensive plan, giving them as a doctor attendance and advice gratis every day in the year.”

Jonah Barrington, responsible for some of the most entertaining and colourful memoirs of late eighteenth century Dublin.

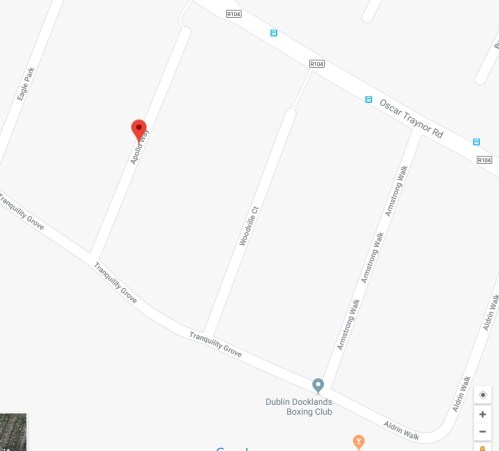

With public subscription, Borbumborad succeeded in opening his Turkish Baths beside Bachelor’s Walk in October 1771, supported by dozens of parliamentarians, surgeons and physicians. The baths were a great success, Barrington proclaiming that “a more ingenious or useful establishment could not be formed in any metropolis.” Borumborad constructed “an immense cold bath…to communicate with the River, it was large and deep, and entirely renewed every tide. The neatest lodging rooms for those patients who chose to remain during a course of bathing were added to the establishment, and always occupied.”

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.