Hidden in the middle of a 1970s housing development in Rathfarnham lies the ruins of a Georgian home, boasting a fascinating history.

Known as The Priory, this house which stood for at least 150 years, played an integral role in “the greatest love story in Irish history”; that of Sarah Curran and Robert Emmet.

Its journey from a beautifully well-kept homestead to a vandalised ruin sums up the unfortunate recurring story that sees the Irish State and other bodies not doing its job in preserving objects of great historical interest.

The house, which was linked to secret societies, wild parties, underground passages, fatal accidents, ghosts, secret rooms and a long-running quest for a forgotten grave, has all the hallmarks of a fantastic melodramatic thriller.

The mystical entrance into The Priory house. Taken from Footprints of Emmet by J.J. Reynolds (1903).

In 1790, the famed barrister and politician John Philpot Curran took possession of a stately house off the Grange Road in the south Dublin village of Rathfarnham. He renamed it The Priory after his former residence in his hometown of Newmarket, Cork. A constitutional nationalist, Curran defended various members of the United Irishmen who came to trial after the failed 1798 rebellion.

[It has been erroneously reported that Curran took over a residence, originally called Holly Park, which he renamed The Priory. Holly Park was, in fact, the name of the home of Jeffrey Foot which stood to the south of Curran’s home. Foot was an Alderman of Dublin Corporation who followed his father’s footsteps into the tobacco and snuff industry. Holly Park later became St Columba’s College and is still in use.] [1]

One of Curran’s earliest biographer’s, William O’Regan, described the view from the second floor of The Priory:

of interminable expanse, and commanding one of the richest and best dressed landscapes in Ireland, including the Bay of Dublin; on the eastern side May-puss Craggs and obelisks, and a long range of hills.

O’Regan described the house itself as “plain, but substantial, and the grounds peculiarly well laid out and neatly kept”. One source, The Irish Times on 14 August 1942, suggests that the higher proportion of the house was the part that Curran rebuilt with the rest of the dating back to the Queen Anne period (1702–1714).

A window under a large box tree beside the house was said to have been the venue for Sarah Curran’s final goodbye to Emmet in 1803. More on their relationship later.

The Priory as it would have looked from the 1790s to the 1920s. Pictured in 1903. From Footprints of Emmet by J.J. Reynolds (1903).

Curran was a founding member of an elite patriotic drinking club called The Monks of the Screw (a.k.a. the Order of St. Patrick) who were active in the late 1700s. The membership, numbering 56, included politicians (Henry Grattan) judges (Jonah Barrington) priests (Fr. Arthur O’Leary) and Lords (Townshend). Many were noted for their strong support of constitutional reform and self-government for Ireland. The club used to meet every Sunday, in a large house in Kevin’s Street owned by Lord Tracton.

Given the title of the ‘Prior’ of the Monks, Curran used to chair their meetings at which all members wore a cassock. It was he who wrote their celebrated song whose first verse goes:

When Saint Patrick this order established,

He called us the Monks of the Screw

Good rules he revealed to our Abbot

To guide us in what we should do;

But first he replenished our fountain

With liquor the best in the sky;

And he said on the word of a Saint

That the fountain should never run dry.

Curran also used to host the Monks at his home in Rathfarnham in a special room situated to the right of the hall-door. The two outside legs of the table, at which they would sit, were carved as satrys’ legs. Between them was the head of Bacchus (God of the grape harvest and winemaking) and the three were wound together by a beautifully- carved grapevine. It was also written that an elegant “mahogany cellarette in an arched recess in another part of the room was cap able of holding many dozens of wines” [2]

The parties, as can be imagined, were all-night affairs. Wilmot Harrison in his book Memorable Dublin Houses (1890) wrote that:

Ostentation was a stranger to his home, so was formality of any kind. His table was simple, his wines choice, his welcome warm, and his conversation a luxury indeed … There were beds prepared for the guests, a precaution by no means inconsiderate. When breakfast came it was sometimes problematical how the party were to return. If all were propitious, the carriage was in waiting; if a cloud was seen, however, the question came “Gentlemen, how do you propose getting to court?”

The house was allegedly haunted by a mischievous ghost who spent most of his time in a secret room of the house, which was eventually closed up by Mrs. Curran.

Tragedy struck on 6 October 1792 when Curran’s youngest daughter Gertrude accidentally fell from a window of the house and was killed. Devastated at the loss of his favourite child, Curran decided to bury his daughter, not in a graveyard, but in the garden adjacent to The Priory so that he could gaze upon her final resting place from his study in the house.

Little Gertrude was buried in a vault and a small, square brass plaque was put on the stone slab reading:

Here lies the body of Gertrude Curran

fourth daughter of John Philpot Curran

who departed this life October 6, 1792

Age twelve years.

Grave of Getrude Curran, killed aged only 12 in 1792. From Footprints of Emmet by J.J. Reynolds (1903).

Sarah Curran’s last request on her death bed was to be buried “under the favourite tree at The Priory, beneath which her beloved sister was interred” [3] but Curran did not agree to this. Lord Cloncurry told Richard Robert Madden, historian of the United Irishmen, that Curran did not accede to the request because he had been previously criticised for burying Gertrude in unconsecrated ground. [4] The fact that Curran also disowned and essentially banished his daughter Sarah obviously had something to do with it as well.

The story of Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran would be known to many. In a nutshell, the Irish Nationalist Emmet was introduced to the beautiful Sarah through her brother Richard whom he knew from Trinity College. They fell madly in love but Curran’s father did not approve of their relationship. After clandestine meetings and many love letters, they secretly got engaged in 1802. Following his abortive rebellion against British rule the following year, Emmet fled to the Dublin Mountains but was caught after he tried to visit Sarah at The Priory. From his cell in Kilmainham Jail, he wrote a letter (addressed to “Miss Sarah Curran, the Priory, Rathfarnham”) and gave it to a prison warden whom he thought he could trust to deliver it. Instead, it was handed in to the authorities and Curran’s cover was blown. The Priory was raided by the British and Sarah’s sister Amelia only just succeeded in burning Emmet’s letters.

Emmet, aged 25, was then hanged and beheaded on Thomas Street on 20 September 1802. Curran, disowned by her father, moved to Cork where she married a Captain in the Royal Marines. Accompanying him to Sicily where he was stationed, she contracted TB and died in 1808, aged 36, after they returned to Kent, England. As mentioned earlier, her father refused to let her be buried at The Priory and so was laid to rest in the family plot in Newmarket, Cork.

View of The Priory ca. 1865-1914. Robert French, The Lawrence Photograph Collection. National Library of Ireland.

John Philpot Curran, a broken man after the deaths of two of his daughters and with his wife leaving him for another man, continued to live in The Priory until his death in 1817. From all accounts, he cut a lonely figure who wandered the gardens of the house at all hours of the night and wept by his daughter’s grave.

What follows is the story of the once magnificent Priory and its slow journey into nothingness.

On 14 October 1922, a journalist by the name of “Swart” wrote a long but beautifully- written article in The Irish Independent entitled ‘John Philpot and the Priory – Some incidents recalled’. He wrote that:

Nestling amidst its groves of beech and chestnuts, the Priory still bravely shows a semblance for its former prosperous condition. What tales of reverly or love its old walls might repeat! What days of joys and sorrow in the lives of its occupants has it beheld!

Most interestingly, he suggests that this “country villa (was) the successor of a homestead which existed as far back as the sixteenth century”.

Swart continues:

We approach it through an open drive, guarded by old-fashioned gates of evident antiquity. Standing on the now moss-grown carriage-sweep before the front door one is conscious of a delicious air of mystery of breathing over all. The grove of tall beech trees flanking the eastern gable, the great dark cedar beside them, shading the door which leads to the gardens at the rere, the spreading timbers of chestnut outside the western gates are silent sentinels which will never betray the secrets of the days that are gone.

Obviously able to gain access to the house easily enough, he wrote that looking from the front windows you could see:

over the the high tree tops in the fields beyond, a misty vision of the city stretches far below, and the distant outlines of Howth Summit and the northern coast become faintly visible. At night the tiny beacons from the harbour bar glow like fair lanterns through the dark

Clearly deeply interested in the house itself as well as the Curran family, Swart wrote that:

the years have dealt ruthlessly with the gardens of the Priory. Once the fond care of the great orator, he converted them into a veritable Eden. Often when touched by the melancholic depression which seems inseparable from the Irish character, he would wander out at midnight to pace a fitful hour through chosen leafy haunts. Many a hoary apple tree, still strangely fertile, after lapse of more than a century has witnessed his long communings but where the violet peeped or in the beds where strawberries fattened in luscious redness, the briar now holds sway and the nettle rears its unlovely head.

Gertrude’s grave marker was still visible in 1922, writing that:

in a tiny grove … a desecrated tombstone still marks a hallowed spot. It is the last resting place of one who in a short life brought great sweetness to those held her most dear … When she died in her twelfth year, he could not bear the thought of separating her from the surroundings to which she had so much gladness. They buried (her) in sight of the old house and with it much of the worldly hopes and aspirations of her sorrowing father.

On 23 November 1924, the Sunday Independent’s ‘Special Commissioner’ focused his weekly column on The Priory.

This series of articles, entitled ‘Sunday Rambles in Dublin’, centered on “chatty articles dealing with places of interest to short walks around Dublin – outside the confines the city”. This column was spurred on by the popularity of its predecessor ‘Seeing Dublin from the Top of a Tram’.

The Special Commissioner wrote:

Car No. 16 or 17 will take us … to Rathfarnham for 4d … About three-quarters of a mile (past Loreto Convent), we meet … “The Priory” on the left hand side. The old house is about a hundred yards from the road, and we find it to be a long low building typical of the cottage type of country residence fashionable in the 18th century … (it) has changed so little during all those years that it does not require a very long stretch of imagination to see Ireland’s heroine, the gentle Sarah Curran, standing at the door of “The Priory” impatiently waiting for some message from her sweetheart, Robert Emmet.

On 1 November 1927, M. J. Freeney in his Sunday Independent column on ‘Famous County Dublin Mansions’ focused on the Priory. Freeney describes it as “one of the most interesting (old houses)” in the area and relates that it was a familiar sight at one time to see “a lonely grave over which an old man lies sobbing … every day the same sad sight would have met our gaze: the broken figure of John Philip Curran crying like a child for his youngest and favourite daughter”.

On 9 May 1927, historian John J. Reynolds wrote to The Irish Times outlining his disappointment that nothing was being done to help preserve The Priory especially Gertude’s grave:

An inscribed stone was placed over the grave, and a circular group of shrubs was placed to enclose it. These in the course of years had risen sentinel-like to guard this simple tribute of paternal love. The familiar group of trees, together with the fine trees which stood at the entry of “The Priory” has now been felled and nothing save a few ugly stumps remain. Possibly the very grave stone itself in the course of time come to ‘patch a wall to expel the winter’s flow’ … Just now when war memorials – of battles ranging from China to Peru – are fashionable we have, apparently no time to think of a touching memorial left by the fearless advocate of Catholic Emancipation, the defender of Hamiton Rowan, Wolfe Town and the Sheares.

The entrance gates, which had seen better days, of The Priory. From Footprints of Emmet by J.J. Reynolds (1903).

On 30 April 1932 in the Irish Independent, it was announced that The Priory was to be sold by public auction. The site contained “43 acres, 3 roods (and) 20 perches” and the residence, “six apartments and kitchen”. As well, there was a “very fine hay barn, with corrugated iron roof and sides and other offices.”

James Hegarty of Glensk, Rathfarnham wrote to the Irish Press on 9 June 1936 about Gertrude’s tomb:

The plate no longer exists but three of the four brass screws by which it was attached to the stone are still there. The little grave formed the centre of two concentric circles of beech trees probably planted by Curran’s own hand. Vandalism and war-time avarice demolished these conspicuous reminders of a stirring period of Ireland’s history. Less than five years ago the tombstone, a large slab 5ft by 4ft was still intact. It, too, has yielded to the desecrating and destructive spirit of the age. The sacreligious hand of wanton profanation has broken the stone into four or five fragments and time is actively engaged in all traces of a prominent landmark of our history.

Again, Hegarty questions why nothing has been to done to help preserve this historic place:

Is it too much to ask the National Monuments Committee or the authorities of the National Museum to arrest further decay by rejoining the fragments, replacing the inscription, and enclosing the sacred earth by a paling?

Obviously, it was too much to ask.

The celebrated political campaigner Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington asked readers of the Irish Press in 16 February 1937 to take the valuable book The Footsteps of Emmet (1903) and stroll with it around Rathfarnham. She may have done so herself as she writes that The Priory “has lots much of its old world beauty (and) the grave of Sara Curran’s younger sister had its headstone broken”. Following in the footsteps of others, she questions why there hasn’t been more done to help salvage the historic sites associated with Emmet – “Surely the house in Butterfield Lane might have been acquired and set up as a an Emmet museum like Goethe’s in Weimar, the Bronte house at Haworth or Shakespeare’s in Stratford-on Avon”.

In 1939, James A. MacCauley of the Revenue Department visited The Priory and found it in quite good condition. He “went around the rooms and in a study he saw a wall safe of solid granite, with a double door of metal and wood, where Curran kept his papers and valuables”. The staircase, door and windows were intact. However three years later, they all had disappeared and the house was a “gaping shell”. Obviously, the war years were not kind to the house with individuals stripping it of its wood for fuel. MacCauley had looked at the life of John Philpot Curran for his M.A. thesis and had discovered that the lion’s head knocker of the door and some silver from The Priory were in possession (at the time) of Mr Lionel Edward Curran of Vancouver, a descendent of Curran. [5]

An unnamed Irish Times reporter was sent out to visit the house, in 1942, “as a result of reports that part of it had been demolished”.

The article, published on 12 September 1942, described that:

Even from a distance he could see that the house was a ruin. A two storey building of early 18th Century type, half of it is without a roof, and there is a big enough hole in the other half to bare the rafters. Window frames are empty and partially rotted, and the main entrance is without a door … Inside the house, the drawingroom, there were obvious signs of the cattle from the neighbouring fields having the right of way.

The writer was full aware of the historical significance of this drawing room, in which

…Curran probably discussed with his friend, Grattan, their plans to forward Catholic Emancipation, and where, alone, he probably studied the briefs from which he defended the long succession of ’98 men, from Rowan Hamilton to Napper Tandy. In the back part of the house, in a room which was probably once a pantry, our reporter found a cow stabled.

However, one sign of remembrance of things past did comfort the reporter:

When he was looking for the house, met on the road two little barefooted boys of seven or eight years of age. “What is that house in the middle of the fields?” he said, pointing to the ruin. “Sarah Curran’s house” they both replied, almost together.

IIn an article entitled ‘Monks of the Screw – Where Famous Order Met’ in The Irish Times (18 September 1942), another unnamed writer offers some new information into the deterioration of The Priory:

After the house became empty it was impossible to keep it in good repair, for it was continually raided by seekers after firewood … the slab that covered the grave of Curran’s favourite daughter was shattered under maliciously dancing feet, and now has disappeared. The garden is a wilderness, and the cattle find difficulty in browsing here.

In regard to the house’s furniture:

(it all has seemed) to have disappeared, though a figure of St. Patrick, once the occupant of a niche in the Monks’ meeting place, was seen some years ago in a Dublin public house. The knockers of the door was sent some thousands of miles away to a descendant of Curran. The timber of the house has largely helped to warm some of the more unscrupulous poor, and the house is a complete ruin.

It was reported in The Irish Times on 4 November 1943 that a seventeen old girl, Bridget B (surname withheld for privacy) from Dunlavin, Co. Wicklow was found lying unconscious in rain-soaked clothing on a pile of rubble in the ruins of The Priory by a man walking his dog. She had been missing for four days but made a full recovery in hospital.

In the mid 1940s P.F. Byrne of the Old Dublin Society was cycling in Rathfarnham when he met William J. Jacob a Pioneer committee member. Jacob pointed down to the ruins of The Priory in a field below and said:

isn’t that a disgrace, in any other country an historic house like that would be preserved as a national monument

Byrne had visited the site a few years previously with a friend and had

climbed the stairs of the house – the doors and all available woodwork have been pulled down by intruders for use as firewood (owing to the War there as a fuel shortage). We looked into what was once Sarah Curran’s bedroom and her father’s, the large front one. In the drawing room there was a recess which probably once hid a safe. Flowers still grew in the garden at the back.[6]

A concerned Dubliner and well-known writer, Mervyn Wall, wrote to The Irish Times on 13 September 1950:

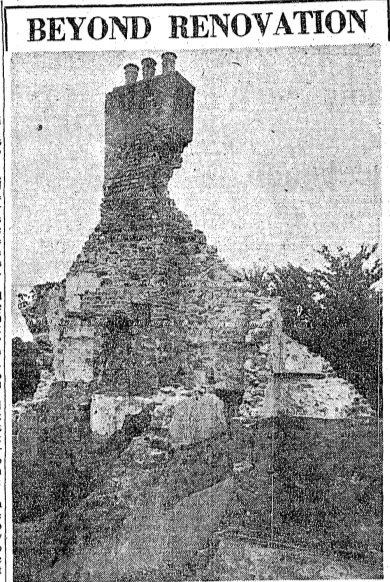

I was one of a party which visited (The Priory) last Saturday with the object of checking reports of recent further destruction there. Some high pieces of wall still remain, and some heaps of fallen stone, very much overgrown. The rest is stubbly fields. Within the past twelve months the main doorway (which gave character to the ruin) and most of the front wall have been overthrown – by local children, who were told … use the place for play.

In regard to grave of Gertrude Curran, Wall wrote:

What is thought … is the grave was pointed out to us. It was completely unidentifiable from the surrounding ground, as the whole area has been recently been subjected to intensive agricultural operations. The gravestones has been smashed in pieces, and, we were told, had last seen some years ago in a neighbouring ditch. Despite diligent search, we were unable to find it.

Wall was informed that the gable and chimneys of the house were to be torn down in a fortnight’s time as there was reason to believe that they were structurally unsound and may fall on the children who played in the ruin.He was frank in his views about how it was a disgrace that such a historic building was left to whittle away:

Indeed some with a sense of retributive justice may regret that persons other than unschooled children will not be standing under that wall the next time the wind is in the west. This is an uncharitable thought but Saturday was a hot day, far too hot to be searching for the violated brave of an eighteenth century girl, and to be carrying in one’s mind the greatest love story in Irish history.

On 14 September 1950, Professor Felix Hackett, Chairman of the Council of the National Trust of Ireland, told The Irish Times that “it was not part of their function to repair the errors of the past, and that the dilapidation of the building had gone so far as to make it impossible to renovate”.

View of a section of The Priory in 1950, showing just how much damage had been done over the years. The Irish Times, 14 September 1950

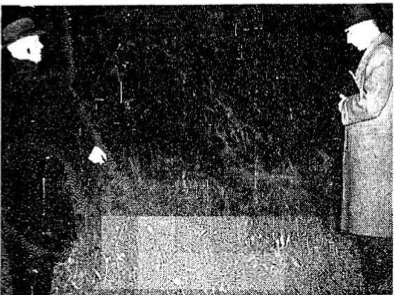

On 11 November 1953, the Irish Press published a story about The Priory and the continuing quest to identify the exact place of Gertrude’s grave. Patrick O’Connor, assistant librarian in the National Library and a Rathfarnham resident, brought a Irish Press photographer to the ground of the Priory and showed them the spot where he believed the grave lay. Doing so, the journalist hoped that the “long-forgotten grave … (will be) marked and saved from obscurity”.

Joseph O’Connor (left) pointing out the location of Gertrude Curran’s grave to an Irish Press reporter. The Irish Press, 11 November 1953.

O’Connor told the newspaper:

It was fifteen years ago since I had been there. But it was many years before that I saw the trees and the stone. In 1924 only the stumps of the trees were there. The stone had been smashed it is thought, and thrown into a ditch.

[The article noted that Patrick O’Connor, as a youngster, had often seen Patrick Pearse in the grounds of nearby St. Edna’s and he would later himself be active with the 4th Battalion of the I.R.A.]

On 23 June 1962 in the Irish Independent, it was announced that The Priory was to be sold by public auction again. The site this time around contained “12 acres, 1 rood (and) 30 perches”. It was described as an “unusual Tudor-style red-brick detached residence … (standing) over 12 statue acres and a road frontage of almost 1,100 feet”. Inside, there is a “large, spacious hall; large downstairs drawing room dining room, four bedrooms, kitchens with sink … cloakroom and W.C.” Obviously, this advertisement felt it shouldn’t publicise the actual dilapidated state of the house.

It was announced in the Irish Press on 25 February 1964 that the Robert Emmet Society had decided to “proceed with the proposed memorial to Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran at the Priory” that will consist of “twin evergreen oaks and a plaque in a lawn plot beside the ruins of the house”. This plan obviously never came to fruition.

In 1976, it was announced that a new housing development would be built on the site in and around The Priory. This gave local resident and member of the Old Dublin Society, Bernadette Foley, the chance to search through the “weed-strewn patch of ground near her home hoping to find the long sought grave of Robert Emmet” as announced in the Irish Press on 9 October 1976. Local legend suggested that Emmet’s body had been smuggled out after his execution and buried beside that of Sarah Curran’s sister Gertrude.

Modern map (c.2012) overlayed with map from c. 1900 showing location of Priory in relation to housing development.

In her search, she was joined by a “Mr. Mooney” who remembered seeing the vault, 20 years previously. Foley told the Irish Press on 12 October 1976 that “he showed it to me, concealed under a ditch”. The article expressed hope that the Dublin County Council would now do all it could to help preserve the burial place.

Mooney and Foley had found the “remains of a vault hidden beneath a hedge … it was broken in pieces and though it bore the nail marks where there had been a metal plaque of some kind, the plaque itself was gone” reported The Irish Times on 15 October 1976. The article announced that members of three different historical societies believed that Robert Emmet’s body may have been moved there at some point. James Robert-Emmet, great great grand-nephew of the patriot, was said to have been very enthusiastic about the theory.

Patrick Healy in his book Rathfarnham Roads (2005) who was involved in this archaeological work can take up the story:

With the cooperation of Messrs Gallaghers, the developers, a small group undertook to investigate the site. First the exact location was checked on the original large scale manuscript map in the Ordnance Survey, next the field was carefully chained and the site marked to within a few feet and then a narrow trench 3 feet deep was dug through where the burial should have been. The result was a complete blank. A second and a third trench were cut at intervals until a large area had been investigated without finding any burial, timber, brick or stone.

Patrick Healy pictured with spade was part of the team which undertook an archaeologiical investigation at Priory in 1976/79 in search of Gertrude Curran’s grave. Credit – Patrick Healy

Unfortunately they were not able to find evidence of a vault:

The developers then offered to investigate further with the excavator and carefully cleared an area of 20 yards long and 10 yards wide to a depth of 4 feet without finding any sign of disturbance. They then deepened this area by another two feet with no better result. All the accounts of the burial state that it was made in a vault and it is therefore surprising and disappointing that no evidence whatever was found and there does not seem to be any obvious explanation for it.

The related news coverage prompted Arthur Killingley of Enniskerry, County Wicklow to write to The Irish Times. In an article published on 6 November 1976, he wrote:

I have a clear recollection of that grave as I knew it from my childhood. There used to be a delightful short-cut from Grange Road down to the Priory: over a stile where the garden wall of Eden ended and a long a field path which led past some old mark holes and across a meadow to a charming little woodland glade in the middle of which was a gravestone marking the grave of Curran’s younger daughter, sometimes wrongly described by popular legend as ‘Sarah Curran’s grave’

Killingley continued:

The grave once had a plaque bearing an inscription but this was ripped off by vandals over 60 years ago. The Priory estate was at one time very well wooded, but most of the trees, including the grove of trees round the gravestone, were felled by the person or persons who gained permission of the land after the last occupant left The Priory.

Later that month, Dubliner Seamus De Burcha (nephew of Peader Kearney and cousin of Brendan Behan) told his own story in a letter published in The Irish Times on 16 November 1976:

In 1956 The Priory stood as a roofless pile, and I was shown over it by my cousin, a Loreto nun. The square stone slab over Gertrude’s grave remained, but the brass slave had already been removed … The Curran property was then in possession of the Loreto Order. The hall door had been removed when the house was unroofed, and had been erected as a stable door. With the permission of Mother General I replaced the door and, if I may be excused for saying so here and now, I rescued the door. I have it on a wall in Dame Street at this moment, where it was repainted by an artist friend … Soon afterwards The Priory was reduced to rubble and was used as ‘filling’ in the construction of new schools in Rathfarnham.

I wonder where the door is now? Seamus De Burcha worked with the firm P.J. Bourke, theatrical costumiers of 64 Dame Street, until its closure in 1994. Number 64 is now Peadar Kearney’s pub.

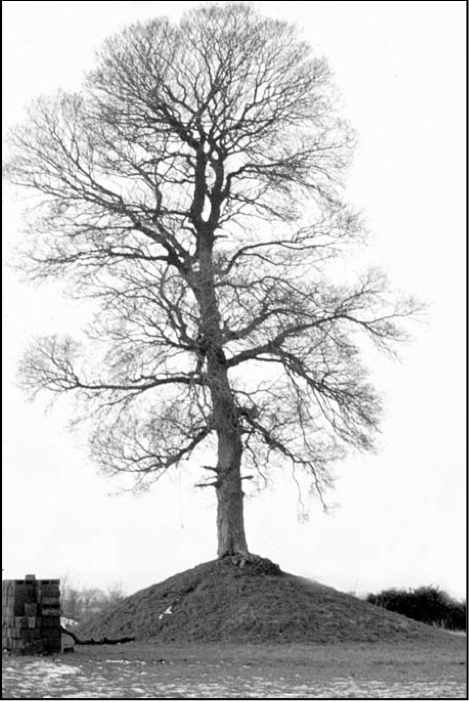

In 1986, an artificial mound with a tree growing on top of it beside The Priory, was demolished when houses were being built on an adjoining site. There is no information available about this and it may have been a prehistoric burial site. An underground passage was exposed which was investigated by local children.

The Priory was occupied by the Curran family from 1790 to 1875 and subsequently by the Taylors until 1923. It fell into chronic disrepair during the 1930s before being wrecked beyond salvation during World War Two. It was more or less totally demolished by the 1950s.

However, today quite amazingly, some ruins of the house can still be seen in the field surrounding the Hermitage Drive, Hermitage Park and Eden Crescent roads.

1988 view of ruins of The Priory in Hermitage Estate. Notice graffiti. Credit – Patrick Healy (southdublinlibraries.ie)

A close friend who lives in the area remembers as children in the early 1990s:

(climbing) the stables and trying to estimate where (Gertrude) fell and where her body was. We spent ages trying to figure out if the blocked door was wide enough to be covering a passageway underneath it. Pretty morbid playtimes… But it is quite the local legend.

It is shameful that such a historic building does not even have a small plaque to tell people of its significance.

1992 view of the Priory ruins in the Hermitage Estate. Credit – Patrick Healy (southdublinlibraries.ie)

The ruins as of today are popular with local teenagers as a meeting place to hang out and drink. Litter, graffiti and the smell of urine now blight what is the last remnant of Sarah Curran’s house, The Priory.

The view of the overgrown ruins can be viewed on Google Map here.

—

[1] Desmond F. Moore, An Epilogue of the Nineteenth Century: John Philpot Curran and His Family, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Apr., 1959), pp. 50-61

[2] The Irish Times, 18 September 1942

[3] Richard Robert Madden, The United Irishmen, their Lives and Times (London, 1842-5), 532

[4] The Irish Press, 11 November 1953

[5] The Irish Independent, 18 September 1942

[6] Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Sep., 1985), p. 125

Refs:

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

Great post, one of your best ever. What a travesty it was let go, and still no official recognition of the site’s historical importance.

Is there not a theory that RE’s body ended up in the grounds of Kilmainham Hospital?

Great post.

It’s the same ol story.

A country with an almost vindictive attitude to it’s own history. Over the years I’ve heard countless stories of archaeological finds uncovered during building work only to be hushed up and covered in concrete forever.

Incidentally the Geoffery Foot mentioned I believe was the son of the famous Tobacconist Lundy Foot of Blind Quay and later Essex Bridge. The business was eventually bought out by PJ Carroll’s.

PS: in this version [ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11262271 ] Curran spent the last 3 years of his life in London and died at his house in Brompton on October 14, 1817.

Incredible post, really love it and such a shame to lose this for a housing estate. I think my wife worked in the 90s with the daughter of the developer who still lived in the estate. Great, great post, well done. I live in Ballinteer and it is such a shame that the place of Emmet’s capture is not recognised.

Well done

Fantastic post. I grew up not too far from there and often wondered what those ruins were. As you say, it’s baffling that nothing was done to save the building and that there’s nothing to mark the history of the site.

Reblogged this on A Drink With Clarence Mangan and commented:

“She is far from the land where her young hero sleeps” — The fate of Sarah Curran’s house in Rathfarnham

Ah, ‘the ruins’! I grew up in the housing estate next to that one, and went to the school there beside it. The teachers would walk us to the Pearse museum in Enda’s park and on the way tell us the history of Sarah Curran’s house, the love affair and how Emmet’s body was smuggled back to be buried with hers. After school, when we played on the walls, we were trying to use our homemade ouija boards to call up the ghost of the woman who died there. But, after reading the article, I think we were actually trying to call up the spirit of Bridget, not Gertrude. Years later, we’d traipse past and mess about there when we started knacker drinking -probably contributing to the destruction of the ruin. Shit. Thanks for the article. Interesting, but sad to think of the state of it and so much history lost.

Great comment, thanks.

re: Bridget. She didn’t actually die, I should have made that more clear. Have amended article.

ah ok, could we have been looking for her body then? probably not. confused now!

I have been aware of fragments of this sorry tale for years. Thank you for bringing it all together. Once again CHTM proves itself to be the premier custodian of Dublin history. Thank you.

Our pleasure Bob. Thanks for the comment.

This is a CHTM tour de force! Great article, thank you.

[…] forgotten Jemmy Hope, the Irish Republican revolutionary of the late 1700s and early 1800s, and a look at “The Priory”, the now sadly forlorn home of Sarah Curran, Robert Emmet’s great love. I recommend a reading […]

particularly interesting article lads. thumbs up, maith sibh

This is just brilliant! So interesting, and such a shame it’s not better known. Thanks guys!

Read this article yesterday and was captivated by it. Hopped on the bike and went out to the site today. Such a tragedy that this has been left to decay like this. Even the most modern pictures from 92 on this article flatter to deceive. It’s almost completely overgrown now, full of empty cans and graffiti. No sign of a grave site and no sign that it is appreciated by locals.

Good stuff. I grew up in the estate next to it. The ruins still managed to carry on the tradition of drinking and “romance” for a lot of Rathfarnham teens.

A very interesting story. I was not aware of all the above.

I thought it would have included Sarah’s visit to Tivoli and Glanmire Co.Cork.

History should never be ruined .

Hi there, any chance I could contact the writer of this? I’m doing a project on The Priory as I live right beside it and would really appreciate talking to you!

Unbelievable! Reading this article I began to question more and more where the ruins, or location of this house was, and sure enough I live round the corner and walk past them going to the bus every day. I had NO idea they were of any significance or relation to Sarah Curran.

This is why CHTM is the greatest.

Thanks for the comment Johnathan. Best wishes.

Good to know that despite the neglect in the distant and recent past, people are taking an interest in their heritage. I was glad also to see that my father, Arthur Victor Grevatt Killingley (1897-1979), who grew up in Whitechurch Vicarage, contributed his memory of the place.

Dermot Killingley

Dermot – I think that your uncle sat beside the future film director, Rex Ingram, in Latin class in St Columba’s. Here’s why (in a letter home):

My Dear Mother

I am getting on very well I was third in weeks order this week and I shall soon be top I am getting next to Killingly in L prose. But I think his pater must do some of his for him as he never has any mistakes and always does the whole of the arithmetic papers.

Ruth Barton

I am pleased to report that I have been trying to get South Dublin County Council involved in some restoration/tidy up of the ruins of this wonderful piece of history since 2009. I have succeeded in so far as it is possible. I am a resident of Hermitage where the ruins of The Priory still stand and over the course of 2 local election campaigns I finally got things moving in 2019.

You see the progress for yourself in this dedicated facebook page by clicking on the link. https://www.facebook.com/prioryruinshermitage/posts/429818845294779?comment_id=431098448500152

You can also contact me by email on prioryhermitageruins@gmail.com

I do not live here, but my bloodlines originated from Rathfarnham 226 yrs ago, in 1788 my great, great, great grandfather Malachy Crowe was born not far from here, he married a local girl Margaret Creaghan and they had 12 children including my great, great grandfather Michael John Crowe. Malachy and Margaret were provisions dealers and vintners in Rathfarnham from 1852-1869, it’s sad to see things that they would have held so dear, fall into such disrepair and ruination. It deprives not only the community, but Ireland’s diaspora of their heritage and history as well. I have a copy of Robert Healy’s “Rathfarnham Roads” and it gives me a small window into the Rathfarnham that my great, great, great, grandfather grew up in and the Rathfarnham his children lived in.

Thank you to everyone who keeps history alive for future generations.

Maria

for the record robert emmet was not captured at the priory but was arrested in a house where he was in hiding on the harolds cross rd, house is long gone and was situated beside the small supermarket near the canal bridge, another house since demolished around the corner also since demolished was thought to have been where he was arrested ,but not accurate, maitiu standun.

A lot of years ago, 30 or more, when I was walking from Marley towards the grange road and passing the site I came across a guy on a bulldozer/ excavator and I asked him what he was up to..if he knew what the site was and to this day I remember his reply..’it’s just a hape o’shite’he said..I didn’t know if he was there legally and moved on…when I came by later on he and his machine were gone and nothing had been done to the site…the same sad pile!

John Philpot Curran, a broken man after the deaths of two of his daughters and with his wife leaving him for another man, continued to live in The Priory until his death in 1817. From all accounts, he cut a lonely figure who wandered the gardens of the house at all hours of the night and wept by his daughter’s grave.(this from article above is incorrect.) JPC died in London in 1817 as per the following.

Death

He retired in 1814 and spent his last three years in London. He died in his home in Brompton in 1817. In 1837, his remains were transferred from Paddington Cemetery, London to Glasnevin Cemetery, where they were laid in an 8-foot-high classical-style sarcophagus. In 1845 a white marble memorial to him, with a carved bust by Christopher Moore,[9] was placed near the west door of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

I grew up with that in front of the house. My parents bought a house there in 1980. As kids we used to climb the walls and play hide and seek around the old house and trees and chasing along the tops of the walls.

We heard the old stories, and there is a tree lined path in St Enda’s Park that local legend said Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran used go walking and courting on.

Thanks for such valuable information.

My Grandmothers Birth Cert. Shows her birthplace as The Priory. Rathfarnham. In 1889. I think her father may have worked there.

I stumbled across this article as I as searching for information on the destitute ruins that sit somewhat out of place in Hermitage estate, I live in nearby Eden and it was a pleasure to read into the local history apparent on my doorstep, thank you for your efforts.

Do come and visit the restored Priory ruins and plaque

I heard of the local legend that Sarah had Robert Emmett’s body reinterred following retrieval from Bullys Acre close to where her sister was buried which was at the entrance to the house.

Legend has it that two trees were planted to mark the grave one at his head and one at his feet.

It would explain why she wanted to be buried there. It would also explain why her father disowned her at the time if he rumbled that she had his remains interred beside his beloved daughters grave that he would look at from his study. He was obviously no ardent fan of Emmett! The trees were possibly also a camouflage for the disturbed ground? Historically they were used to protect remains from discovery by officialdom and yet mark the place.

If the remains were discovered I imagine Curran would have had the remains removed so there is possibly more to this story?

Fascinating story and shameful to think this is how we treat our heritage.

That clearing is still open ground looking at Google earth I wonder if the there could be an effort made to fully investigate the site. I imagine the last effort when the builder “cleared the ground” possibly destroyed any remaining evidence however, I think with the technology available today it could be assessed with minimal intrusion?

I am pleased to report that I have been trying to get South Dublin County Council involved in some restoration/tidy up of the ruins of this wonderful piece of history since 2009. I have succeeded in so far as it is possible. I am a resident of Hermitage where the ruins of The Priory still stand and over the course of 2 local election campaigns I finally got things moving in 2019.

You see the progress for yourself in this dedicated facebook page by clicking on the link. https://www.facebook.com/prioryruinshermitage/posts/429818845294779?comment_id=431098448500152

You can also contact me by email on prioryhermitageruins@gmail.com