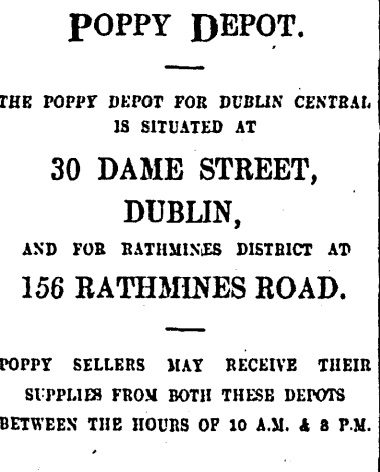

In the Dublin of the 1920s and 30s, the selling of the Flanders poppy was commonplace. Every year the British Legion would open ‘Poppy Depots’ in the city, and beyond it in places like Rathmines, and every year without fail the presence of the symbol on the streets of Dublin was enough to instigate violence. Hand-to-hand fighting, flag burning and even attempted arson on poppy depots pop up in the newspaper archives from the period.

The poppy was formally launched in Ireland by the British Legion in October 1925, though it had been sold on the streets for years before that. The selling of the poppy brought in huge revenue to the body. In March 1930, at the annual conference of the British Legion in Dublin, it was claimed that Poppy Day had raised £487,272 in the year gone, against £469,215 the year previous. These were very significant figures, but the organisation existed for a variety of reasons beyond commemoration. At that same conference, A.P Connolly of the Legion bemoaned the fact that tens of thousands of WWI veterans were in dire need of housing assistance.

The Irish Times wrote in October 1925 that:

The sale of poppies benefits disabled ex Service men who are engaged throughout the year in making them, and also a large number of deserving ex-Service men who are assisted out of the profits. The men employed in manufacturing the emblems are badly disabled men who would stand small chance in the ordinary labour market.

Much of the opposition to Armistice Day, or ‘Poppy Day’, was instigated by republican activists, many with an IRA background. Indeed, during the revolutionary period itself,Armistice Day had been opposed by the IRA, who had considered taking very drastic action against it. George Joseph Dwyer, a member of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA, remembered in his statement to the Bureau of Military History that:

An Armistice parade was held in Dublin in the year 1919 to commemorate the entry of the Allies into the Great War. We paraded under arms and took up positions in Dame Street and George’s Street. We were to open fire on the parade but at the last moment this instruction was cancelled. On our way home we observed a camera man who had taken pictures of the parade. We took the camera off him and destroyed it.

Organisations in the late 1920s and early 1930s like the ‘League Against Imperialism’ drew heavily from the ranks of the IRA, while Eamon de Valera also addressed an anti-Armistice Day rally in 1930, in the capacity of Fianna Fáil leader. On that occasion, Dev shared a platform with IRA radicals Peadar O’Donnell and Frank Ryan, as well as Sean Murray of the Communist Party of Ireland and Sean MacBride. On the eve of Remembrance Sunday, he claimed that if Ireland were free “there would be no such a thing as the demonstration we will see tomorrow.” He went on to state that those opposed to the day “were not unmindful of the comrades who were anxious to honour the memory of their dead companions. But objection was being – and properly – taken to those who on each Armistice Day took the opportunity of indulging in a flagrant display of British Imperialism.” Two Union flags were burnt at the conclusion of the meeting. It is not surprising that after coming to power in 1932, Fianna Fáil representatives largely stayed away from such gatherings.

‘Poppy-snatching’ became something of a sport in Dublin. In 1926, it was reported that as ex-Servicemen were passing the junction of D’Olier and Westmoreland Street as they paraded through the city, “a crowd of between 200 and 300 men and boys, also marching in military formation, came from the direction of Westmoreland Street and headed as if to cut straight across the process ion, their leaders shouting ‘Here we are again’ and ‘Up the Republic!'” Poppies were grabbed from lapels and trampled. The Irish Times reported that “there were many motor cars in the city..decorated with poppies and Union Jacks. When some of these cars came to a stand-still the decorations were torn off the bonnets.”

In 1932, Gardaí “drew revolvers and fired about half-a-dozen shots” over the heads of crowd who threw stones at poppy depots and snatched poppies. Windows were smashed at businesses who sold the emblems. The poppy depot on Dawson Street was often targeted, once even for arson. Kathleen Kavanagh, a 27-year-old from Dorset Street, was sentenced to six months imprisonment in 1926 for “conspiring to set fire to the premises 2 Dawson Street; with having poured petrol on a flag and table, and set them on fire; and with endangering the lives of a number of persons who were on the premises in connection with the sale of poppies.” Beyond arson, there were some other notable interventions. Todd Andrews, a republican veteran of the Civil War who was then a student in UCD at Earlsfort Terrace, remembered that on one year the 11 November commemorations occurred beside the University, and that “when the order was given for the traditional two minutes’ silence smoke and stink bombs exploded in all directions. Mutual abuse and poppy snatching led to scuffles and fistfights until eventually the students withdrew inside the college.”

The numbers participating in the ‘anti-imperialist’ events could grow to thousands, but there were also tens of thousands partaking in the British Legion events. In laying out the workload of the Legion, A.P Connolly stated in November 1930 that “there were still 142,000 war widows, 35,000 officers and men who had lost a leg or an arm in the war, 6,450 officers and men who are insane and have been detained in lunatic asylums.” Giving the sheer scale of recruitment in Ireland during the war, not least from working class areas, the numbers taking part in remembering that war two decades later isn’t all that surprising. On the other side, the Irish Independent claimed in 1932 that “a procession of about 2,000 young men” caused trouble in the city, and that “all wore green, white and yellow favours; inscribed with the legend ‘Boycott British Goods.'” The paper claimed that the boys sang and chanted that “we’ll crown de Valera King of Ireland” and shouted “no poppies in this city.” At Trinity College, they sang The Soldier’s Song, but the reply from within the gates was Rule Britannia! The annual singing of God Save The King by Trinity College Dublin at College Green was seen by republicans as a provocative act, but Trinity students were more than willing to stand their ground and it took huge numbers of police to separate the two sides. League Against Imperialism demonstrations could mobilise crowds of 10,000 to 15,000 at College Green.

Marching to the Pro Cathedral, November 1930. Remembrance services occurred in both St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the Catholic Pro Cathedral.

Poppy Day didn’t only annoy republicans, it also troubled the authorities. Writing to the Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy, Colonel Neligan outlined a belief in 1928 that the commemorations were becoming “the excuse for a regular military field day for these persons…if the irregulars (a reference to the IRA) adopted these tactics they would be arrested under the Treasonable Offences Act.” The presence of uniformed British Fascisti members was also highlighted in the press, and troubled Gardaí. Attempts were made by the authorities to introduce restrictions on the emblems and flags on display on Poppy Day, in the hope it would reduce some of the tensions.

‘The Anti-Imperialist’, which appeared on the streets of Dublin on the eve of Armistice Day in 1926 (National Library of Ireland, http://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000511068)

The cycle of poppy snatchers and British Legion marchers beating each other over the head could have continued indefinitely, but in 1934 there came a new approach to the day, thanks to the Republican Congress. A short-lived attempt at establishing a broad left-wing front in Irish politics which could challenge both partition and capitalism, the Congress had emerged from the disillusioned left-wing of the IRA. In its ranks were men like Frank Ryan and Peadar O’Donnell. Ryan had once been instrumental in attacking Legion marchers on the streets, but in 1934 he aligned himself and the Congress with a new initiative. Of Ryan in earlier years, Brian Hanley has noted:

He was seen as a man of action, looked up to by young republicans but also an able and belligerent public speaker. At one anti-imperialist rally he warned the British Legion that “they had put them from Leeson Street to College Green, and from there to the Park, and the next place they would put them would be the bogs. Argument will be met with argument and blow with blow.”

Ryan wasn’t alone in the Republican Congress as a veteran of the ‘Poppy Day riots’. Another activist, George Gilmore, had been in court in 1926 for assaulting a man on Grafton Street, and for stealing a Union flag during Armistice Day riots. Anthony Coughlan, who knew Gilmore, has penned a fitting tribute to him here. Anthony Coughlan, who knew Gilmore in later years, has penned a fitting tribute to him here. An anti-war demonstration, including wounded veterans of the First World War, denouncing war, imperialism and the mistreatment of the war wounded, was certainly a new and exciting endeavor on the part of the left. An appeal to Irish ex-servicemen was issued, claiming that “the Armistice Day parades under the British Legion have been proved for the last ten years to be an insult to the dead and a mockery to the living.” Ryan shared a platform with Irish veterans of the war. Patrick Byrne of the Republican Congress remembered years later that “I had urged this new approach because of the disgust I felt when I saw some ex-servicemen being set upon for wearing their medals and poppies on their ragged coats.”

Frank Ryan himself wrote in the aftermath of the 1934 alternative Armistice Day that:

Did you ever believe you would see me, on an Armistice Day in Dublin, marching beside an ex-British soldier, who wore his Great War medals? For ten years or so, I have shoved my way into the front of the anti-Imperial demonstration. I’ve taken and given blows in clashes with ex-servicemen and police. I claim the record for capturing Union Jacks. Armistice Day was our day for demonstrating against imperialism, and imperialism to us was typified by Union Jacks and bemedaled ex-soldiers, and last Sunday – I walked with bemedaled ex-soldiers.

Frank Ryan and George Gilmore, both veterans of Poppy Day riots who later organised left-wing anti-war alternative ceremonies, appear in this picture of IRA prisoners released in 1932 (NLI, but brought to our attention by Village, see above linked article)

In 1936, there were similar sentiments from Ryan, when he asked a crowd at an anti-imperialist rally not to attack those wearing poppies, stating that “I ask you to give the benefit of the doubt to those who wear poppies tomorrow. Many will wear them in memory of dear friends who were deluded into dying for fine ideals in a horrible capitalist war. Respect them for the love of their dead people.”

The parading of the injured and maimed veterans of the war was a much greater political demonstration than the snatching of poppies. In a similar anti-war spirit, the 1930s in Britain saw the emergence of a white poppy, created by the Women’s Co-Operative Guild, as a symbol of remembrance that was explicitly anti-war, and which had (and has) the word ‘PEACE’ upon it. It was never really worn in Ireland in the 1930s, and only appears in the Irish media in reports dealing with its controversial nature in England.

As the 1930s progressed, ‘Poppy Day’ lost much of its violent edge in Dublin, but the wearing of the symbol also became less commonplace in subsequent decades. In recent years, the wearing of the poppy in British public life has become a great debate however. Brian Hanley’s 2013 article for The Irish Times is well worth reading:

One of the reasons the flower is so omnipresent at this time of year is because it is practically compulsory for those in the public eye in the UK. What one historian has called “poppyganda” is part of a renewed militarisation of British public life. As a group of British veterans of the Iraq war complained two years ago, the build-up to Armistice Day now amounts to “a month-long drum roll of support for current wars”.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

Leave a comment