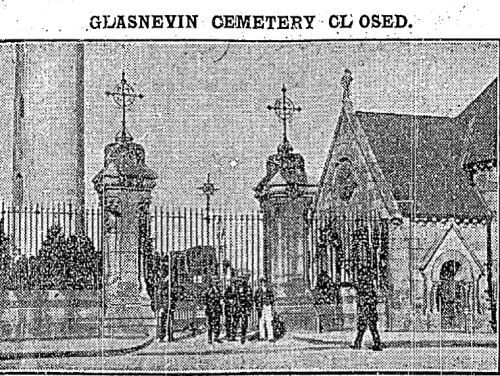

A historic image of Glasnevin Cemetery.

Prospect Cemetery, more commonly known now as Glasnevin Cemetery, is one of my favourite places to wander in Dublin. From ‘Anonymous to Zozimus'( to borrow a phrase) it is the final resting place of more than 1.5 million people. It holds a very special place in republican history too, having witnessed the funerals of figures like Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and Thomas Ashe, which were iconic moments in themselves.

While the most visited graves today are those of revolutionary icons, the story of the cemetery began with a young working class boy. The first burial happened on 22 February 1832, when young Michael Carey from Francis Street became the first ‘resident’ of Glasnevin Cemetery. He was a victim of TB, which was rife in Dublin’s tenements and devastated working class communities.

As the cemetery grew bigger in the generations that followed, so did its staff. Glasnevin’s gravediggers are of course renowned for bestowing an unofficial name upon one of Ireland’s most loved pubs, John Kavanagh’s of Prospect Avenue. As Shane MacThomáis noted in his history of the cemetery, it was common practice for diggers to knock with their shovels on the walls of the pub in the 1870s seeking a pint, but even earlier there had been a close connection between cemetery and pub – in 1836 the Cemetery caretaker, James Moore, complained of finding two unaccompanied coffins lying outside the cemetery, as mourners had crowded into Kavanagh’s.

An advertisement for Kavanagh’s, established in 1833.

This footage from 1974 shows the handing over of two pints through the railings of the cemetery. In reality, it would probably land you in severe hot water!

One interesting aspect of the Glasnevin grave diggers historically has been their grá for industrial action. Indeed, a quick dig into the archives of Irish newspapers shows that in 1907, 1916, 1919, 1920/ 1921, 1937, 1965 and 1971 the gravediggers took strike action, leading to the macabre sight of loved ones burying their own dead.

Why strike? Normally, an industrial dispute is primarily motivated by the wage question, but there were other issues at play. In August 1919, an anonymous grave digger wrote to the Freeman’s Journal, highlighting the fact that “the poor, forlorn gravedigger with pick and shovel is daily risking his life cutting his way to a depth of 9 or 10 feet. Should the earth slip, were the men not always watchful, what would be the result?” The workers’ believed that a man digging graves alone was in danger, requiring an assistant at all times. In an act of sympathetic striking, a popular tactic of the revolutionary period and something Jim Larkin had introduced into Irish trade unionism in a major way six years earlier, the hearse drivers decided to strike in ‘sympathy’ with the gravediggers during their 1919 dispute.

Picketing grave diggers, 1919.

Gravediggers broke their own strike in 1921 for one day only, to bury Archbishop William Walsh, the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin. Walsh hadn’t been a great friend to Irish trade unionists – in 1913 he was vocally opposed to plans to send the children of locked out Dublin workers to England, believing that it would put their faith in danger. The dispute had been particularly bitter, and when it ended in May 1921 one newspaper wrote:

It would serve no useful purpose now to discuss responsibilities for the dispute.The strike, after lasting since November, has closed, and we hope that recriminations will close with it and that no such dispute will again bring added pain to Dublin mourners.

Pádraig Yeates, one of the leading social historians of Dublin life, notes in A City in Turmoil: Dublin 1919-1921 that “so frequent were disputes at Glasnevin…that the Councillors asked their Law Agent to examine whether the Corporation would be legally empowered to open its own cemetery.”

In almost every year of the striking grave diggers, you find accounts of people digging the graves of their loved ones. During the 1971 strike, the media rushed to Glasnevin to get pictures of families in the act, making a pretty bad situation all the worse. Volunteers came forward in great numbers to assist families during that dispute, with the Irish Press writing that “so many volunteer gravediggers have visited Glasnevin Cemetery, to assist bereaved relatives and friends in the task of digging graves during the gravediggers strike, that there have been as many as seven men available to do a job which, in normal circumstances, would be performed by a full-time gravedigger.”

A 1971 newspaper image.

The city owes much to its gravediggers of course, something that becomes apparent in moments of hardship and tragedy. The 1918-19 Flu Epidemic, which John Dorney has noted was a much greater killer than political violence of the time, put enormous strain on cemeteries. To quote Dorney:

…deaths soared in Dublin with the arrival of the flu in July 1918. A total of 36.1 deaths per thousand were recorded in the city in last quarter of 1918, rising to 37.7 in the first quarter of 1919. At the Adelaide hospital 497 admissions with flu and 32 deaths were reported in October 1918 ‘often within 24 hours of onset’. In the city as a whole 250 deaths a week were being recorded by November 1918.

At the height of this tragedy, Glasnevin witnessed 240 burials over a period of only 8 days.The flu epidemic even struck some those who had been lucky to survive the 1916 Rising. Richard Coleman, a veteran of the Battle of Ashbourne, lost the battle to the epidemic in December 1918, and 15,000 followed his coffin from Westland Row to Glasnevin Cemetery.

Today, the cemetery continues to grow. The gravediggers remain, and featured in the very moving documentary One Million Dubliners. Thankfully,their striking days appear to be over.

Glasnevin gravediggers, 1960s. (the men were named by Shane MacThomáis as Tommy Bonass, Tommy Byrne and Benny Gilbert)

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

The gravediggers did in fact have the habit of banging on the wall to order pints. Eugene Kavanagh, the late owner of the Gravediggers, as a boy would bring the pints out and put them throught the railings. He passed away last year.

Another odd thing was that people from Dublin had to be buried before noon. This was due to the fact that many funerals stopping at the gate would end up so late in the pub the gates would be closed. A number of times the sextant would open up in the morning to find a coffin or two aganst the gates. For years I thought this was made up but it turns out to be true. A friend had a copy of the cemetary bye laws from (I think) around 1908 and it was in there. I think the rule was if you lived within 7 miles of the GPO you had to be buried before 12 noon.