Introduction:

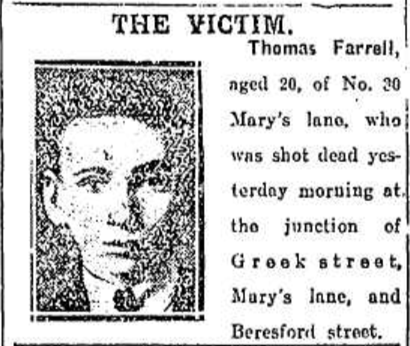

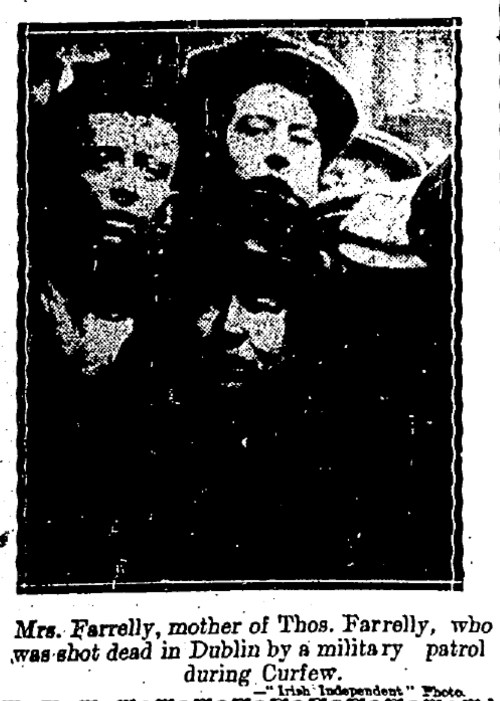

Thomas Farrelly (20), of 30 Mary’s Lane, was shot and killed by the British Army in Dublin’s North Inner City in August 1920. A neighbour Thomas Clarke (19), of 16 Green Street, was seriously wounded in the attack.

It occurred during a turbulent month within a turbulent year. On 7th August, an IRA Flying Column’s ambushed a six-man RIC foot patrol near Kildorrery, County Cork. Two days later, the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act received royal assent giving Dublin Castle the authority to replace the criminal courts with courts-martial and to replace coroners’ inquests with military courts of inquiry. On 12th August, Terence McSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork was arrested and began his hunger strike.

Planned visit of Archbishop Mannix:

During the summer of 1920, the outspoken Cork-born Dr. Daniel Mannix (1864-1963), Archbishop of Melbourne was undergoing a tour of the United States. He shared a platform with Eamon de Valera at Madison Square Gardens in New York telling the audience of 15,000 people that Ireland should be given the “same status in postwar planning as the other small nations of Europe”.

He openly supported the actions and aims of those behind the Easter Rising proclaiming :

I am going to Ireland soon and I am going to kneel on the graves of those men who in Easter Week gave their lives for Ireland.

On 31st July 1920, he boarded the transatlantic liner Baltic at New York for his long journey to Queenstown (Cobh) in his home county of Cork. The ship had made it so close to the Irish coast by 8th August that Mannix could see the lights of Cobh and the flames of huge bonfires of welcome on the hilltops.

But the British government had other ideas and the ship was intercepted by the Royal Navy. Mannix was denied entry to Ireland, arrested and brought to Penzance, Cornwall. Padraig Yeates, in his brilliant book ‘A City in Turmoil‘, wrote that Mannix was prohibited from addressing any public meetings in any part of England with large Irish immigrant populations. He remarked with characteristic irony: “Not since the Battle of Jutland had the British Navy scored a victory comparable with the capture of the Archbishop of Melbourne without the loss of a single British sailor.”

A summer’s night in Dublin

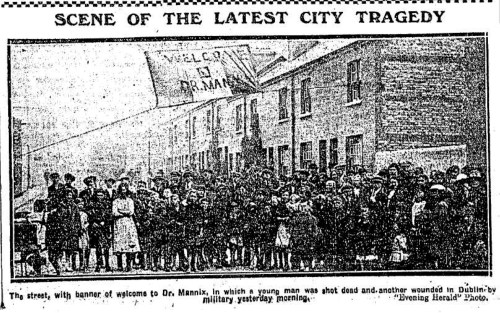

Bonfires to welcome Archbishop Mannix to Ireland had also been lit across Dublin city including one on Greek Street in the Markets area of the North Inner City.

A large Irish tricolour with the wording ‘Welcome Dr. Mannix’ was draped across the street by supportive locals.

On that summer’s night late on 10th August, a small group of about ten young men were sitting around the dying embers of the bonfire at the corner of Greek Street, Mary’s Lane and Beresford Street. Newspaper articles reported that they were singing Irish nationalist songs. During the singing of ‘The West’s Awake’, a truck full of British Army soldiers from the Lancashire Fusiliers pulled up.

At the time, Dublin was under a strict military curfew and people without the necessary permits could not be outdoors from midnight until five in the morning.

At the following inquest, local witnesses like Joseph Eccles of Church Street said: “No challenge was given and nothing was said by the military” before they opened fire.

Thomas Farrelly ran in the direction of his home and was about 20 yards from the front door when he was hit by a volley of bullets. He was carried into his mother’s house and laid on the kitchen floor. According to the Sunday Independent (15th Aug 1920), Farrelly exclaimed “oh mother! oh mother!” and soon died in her arms.

Another young local man Thomas Clarke was shot and wounded in the knee. He limped into the same house where he collapsed on the floor but luckily recovered from his injuries.

Farrelly was rushed to the Jervis Street Hospital in an ambulance but was pronounced dead on arrival.

Funeral

Dr. Mannix sent a telegraph to the Lord Mayor of Dublin:

Just now I can only use this means of thanking you and all my friends in Ireland for their welcome to Irish waters. Kindly convey my heartfelt sympathy to the relatives of the murdered man Farrell. God rest his soul and comfort those who mourn him” (Irish Times, 13 August 1920)

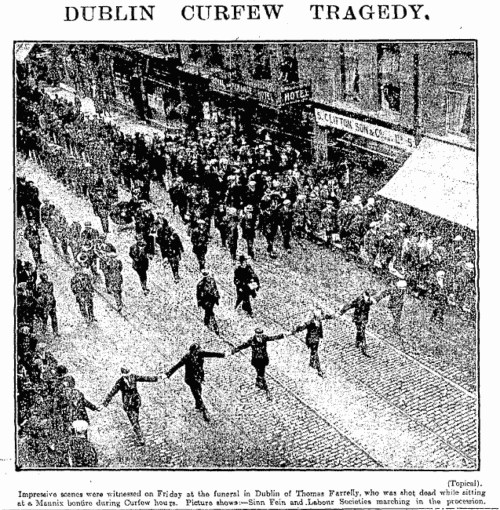

Thousands attended his public funeral which took place on Friday 13th August 1920. The Evening Herald reported that “all shops for a large area around were closed and blinds in private houses reverently drawn”.

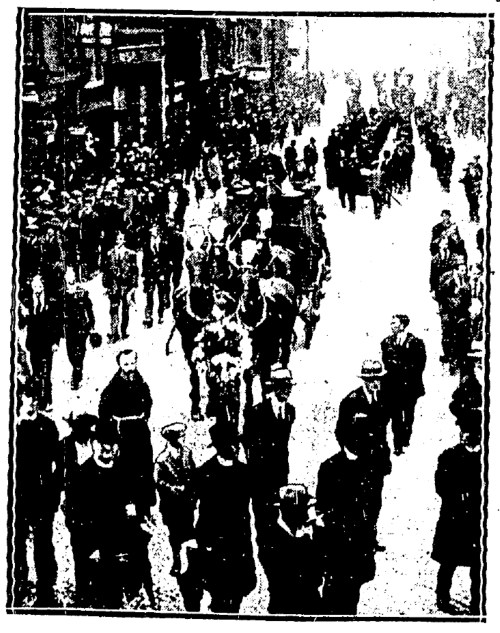

The Irish tricolour flag with the message “Welcome Dr. Mannix” was draped over his coffin. Thomas Farrelly apparently had helped to make this flag which was hung near where the shooting took place.

The hearse was drawn by four black horses from Halston Street Church to Glasnevin Cemetery. Thousands lined the route from North King Street, Church Street, Mary’s Lane, Little Mary Street, Capel Street, Parliament Street, Dame Street, College Green, Westmoreland Street and Parnell Square.

The Herald stated that the scene from Dame Street to the Cemetery was “particularly impressive as the long line of Volunteers, members of the Citizen Army and numerous Trade Unions marched four deep behind the hearse “. A slow, death march was played by the bands of the United Labourers’ Union and the Irish National Foresters.

A number of clergy visiting the city from America and Australia, who had planned to meet Archbishop Mannix, joined the procession. Several hundred casual dockers employed on ships docked at the port also left work to take part in the funeral.

A significant amount of politicians attended including TDs W. T. Cosgrave, J. J. Walsh, Phil Shanahan and Richard Mulcahy.

The prayers at the church and graveside were recited by the Very Rev. Canon Grimley.

Two friends of Farrelly, Christopher Reilly and John Deane, who were with him on the night he was killed led the procession carrying a large Irish tricolour with a black cross in its centre. This was made by John Farrelly, an uncle of the deceased.

A lorry was needed to carry the amount of wreaths and flowers that were donated by friends and neighbours of the Farrelly family.

Thomas Farrelly worked as a van driver for a local firm in the Corporation Market and this is reflected in the messages of sympathy.

A selection of the inscriptions included:

“With deepest sympathy from E. Fagan and E. Browner”

“With deepest sympathy from Mrs. Connor, Mrs. Conway and families”

“To the one who gave his life for his faith and country from two friends”

“With deepest sympathy from his friends, Mrs. Mary Bradshaw and Miss Maisie Mulvaney”

“With deepest sympathy from the friends of Brunswick Street”

“With deepest sympathy from Miss Daly, South City Markets”

“From his comrade, John Tyrrell”

“With deepest sympathy from Mrs. McKenna and Mary Jane McMahon”

“In frond remembrance from Dick and family”

“From Mrs. and Miss Lilly Corry, 87 North King Street”

“From his friends Mrs. Kelly, Mrs. Gibney and Miss. Mooney”

“With deepest sympathy from the neighbours of Church Avenue”

“In loving memory from his friends on Stafford Street”

“With deepest sympathy from Nancy and John Deane”

“In loving memory from his pals of Smith Street”

“With deepest sympathy from the Stafford Celtic A.F.C.”

“With deepest sympathy from Daisy Market, per Mrs. Byrne and Mrs. Quigley”

“With deepest sympathy from Kathleen Curran and his friends of the Corporation Market”

“From Patrick Fagan, in loving memory of Thomas Farrelly who died for his faith and for his country”

Aftermath

In the weeks following his death, collections were made in the area to help financially support Thomas Farrelly’s grieving mother. Due to some reprehensible characters collecting money unofficially, Michael J. Nolan of the Corporation Market had to write to the newspapers to inform all sympathisers that they should only donate directly to himself, another worker in the Market or two local priests.

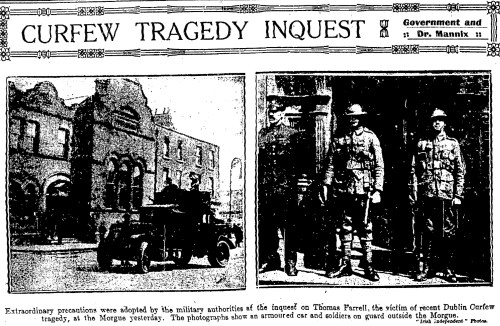

An inquest took place into the shooting at the City Morgue presided by the City Coroner Louis A. Byrne. A large military operation took place with two armoured cars with guns trained on the morgue stationed on the opposite side of the street.

After local witnesses and members of the Military gave evidence, the jury, after an absence of only fifteen minutes, returned the following verdict:

We find that the said Thomas Farrell died on the 10th August, 1920, from shock and haemorrhage, caused by the bullets fired by guns from the military without justification, and we strongly condemn the action of the military in empowering youths to endanger the lives of the citizens. We desire to place on record our deepest sympathy with the relatives of the deceased. (Irish Times, 21 August 1920)

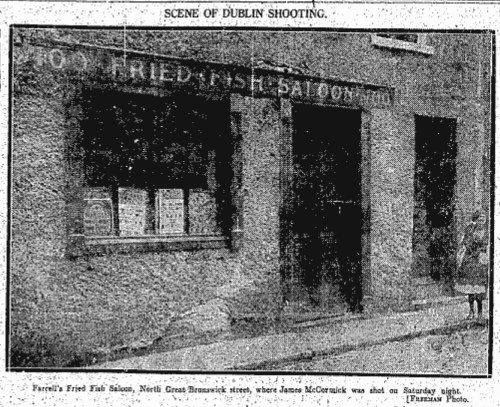

In a tragic state of affairs, an uncle of Thomas by the name of James McCormack (27) was shot dead just ten weeks later. He was employed in a fish and chips shop at 100 North Brunswick Street, Dublin 7 owned by another uncle John Farrell(y) who made the Irish tricolour with black cross for Thomas’ funeral.

Two unknown men in civilian clothing came into the shop at 9pm on Saturday 23rd October and shot dead James McCormack who was working at the time. No arrests were made. A report by Dublin Castle suggested that he was killed for “disobeying an order not to serve soldiers”. This was “emphatically repudiated” by Catherine Farrell, wife of the owner John Farrell, who said the culprits were “complete strangers” to her and to the people of the area. She was making it clear that it was not local IRA volunteers. She told the Freeman’s Journal (25th October 1920) that “Nothing was ever said to us by anyone who we served”.

Farrelly family

Born in April 1900, it has been difficult to trace Thomas Farrelly through the Census returns. The major issue is the variation in spelling between Farrell and Farrelly.

We know at the time of his death in 1920 Farrelly was living with his widowed mother Mary, his brother (15), a younger sister (17) and an older sister (24).

In the 1901 census, I think this Farrell family is the best match. Mary-Ann Farrell (26) was living at 4.3 Ashe Street, The Coombe with her husband Patrick (27), a general labourer, and three children – Catherine (10), Mary-Ann (5) and Johana (2).

In the 1911 census, I believe the same family are living at 2.3 Moore Place and are using Farrelly as their surname. Mary Farrelly (37), “dealer in fish”, was living with her husband Patrick (36), a “market porter” and six children – Mary (15), Thomas (11), Annie (8), John Joseph (5), Kathleen (3) and Michael (4 months).

It’s possible that husband Patrick passed away sometime between 1911 and 1920 and the children’s ages including Thomas match up.

What do you think?

Conclusion

Thomas Farrelly was one of 270 non-combatant men, women and children killed by the British Army in Ireland in a fourteen month period from 1st January 1920 to 28 February 1921. He was listed and named in an address to the Congress of the United States in May 1921.

His memory should be not be forgotten in the streets where he grew up in Dublin.

If you have any further information on either on Thomas Farrelly or Thomas Clarke, please drop me an email or leave a comment.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

Nice piece of research. I love Mannix’s quote. Must have stung at the time.

On a purely peripheral note, I had a relation went down with the HMS Tipperary in the Battle of Jutland (1916) and my aunt emigrated to USA on the Baltic (1908).

Great article. What’s strange is though all my fathers side of the family lived all around that area throughout those years, not one story was passed on. There was never any talk at all about the period.

A well researched and written piece Mr.Sam. Well done. I wonder was there ever any more information brought to light on the murder of James McCormack?

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FRVB-W4F Death of Thomas’ Father?

https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FRLV-XQM Thomas Death?

The killing of James McCormack sounds suspiciously like the murder of the actor Brendan O’Carroll’s paternal grandfather, Peter, who ran a hardware shop in Manor Street in Stonybatter. The ‘Spy in the Castle’, David Nelligan, said the actor’s grandfather was killed by Major Jocelyn Lee Hardy — decorated for bravery during World War One when he lost a leg — because he refused to pass on information about two of his sons – Mr O’Carroll’s uncles – who were in the IRA.

Mr Nelligan wrote: “He was warned that if his sons did not surrender before a given date he would be shot.”

Peter O’Carroll was killed on October 16, 1920, exactly a week before James McCormack and Manor Street is just around the corner from North Great Brunswick Street. Could Hardy have been responsible for both deaths?

very possible! great comment. will try to look into it more.

Hours before O’Carrolls grandfather was shot another man was shot in Capel st. It’s possible it was the same British agents posing as IRA “police”. The young man’s name was William Robinson. A month later his nephew, also William Robinson, was the first one shot in Croke Park.

There is a good Wikipedia article about him – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jocelyn_Lee_Hardy

See also WS0667 – Patrick Lawson. 2nd Lieut. 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade, 1917. Member of the Squad, Dublin, 1921. IRB Member. Page 7

Im a Farrelly My Grandmother my father Matthew and his family lived in 30 Marys Lane we have family still living there. He was born in 1933. Amazing article thank you.

I’m researching another Farrelly family and I thought there might be a link, but haven’t found one. In the course of my research I found the marriage license of Thomas’ parents. They were Patrick Farrelly (sometimes Farley and Farrell) and Mary Farrell (to add to the confusion!) They were married in 1895. After the 1911 census they moved to Stafford Street (side note: one of the sympathies came from ‘His friends in Stafford St) Patrick Farrelly died in 1914 as Linda suggested earlier while they were living in Stafford Street of pyopneumothorax (some kind of collapsed lung or lung disease?).

Maria,

Am also researching the family of Farrellys and McCormacks. There was a suggestion from an older relative of mine that this particular Thomas Farrelly is related to me but like yourself, I have not found a postive link. My Farrellys and McCormacks were from Mary’s Lane/Church St/Beresford St. Please let me know if you would like to compare notes.

Lynn

Thomas Farrelly was my great uncle. I was brought up in 30 Mary’s Lane. My mother’s maiden name is Farrelly and my family still lives there!

Thomas Farrell was my great uncle

Thomas was my great uncle and he surname was farrelly.. his mother remarried in later life and became a Farrell that’s where the confusion comes from..

great research. I am fairly sure that the ‘Fish Saloon’ shown was run by my grandfather John Farrell (address in both censuses is 101 Nth Brunswick St) – (his 2nd son, also John ran a chipper in Nth King st later on.) It seems likely that the uncle John Farrell(y) mentioned at funeral is my grandfather. His wife was a Catherine(nee Quinn) and mother was a McCormick so maybe that links with victim of shooting. Anyone with more info flowing from this?

I’m 13 years old and found out that Thomas Farrelly is related to me.I’m his great great great nephew so he what’s my grandads great uncle.And the owner of the house is my great great aunt but she is currently sick but I found this interesting about my family.