Freeman’s Journal, 21 May 1920.

In May 1920, East London dockers refused to load the SS Jolly George, a ship intended to carry arms to be used against the new Bolshevik state. Reflecting on the event years later, the communist activist Harry Pollitt remembered:

On May 15th, the munitions are unloaded back onto the dock side, and on the side of one case is a very familiar sticky-back, ‘Hands Off Russia!’ It is very small, but that day it was big enough to be read all over the world.

Certainly, the brave stand taken in London would have an impact internationally. The SS Jolly George sailed on without any armaments on board. The leaflets that littered the docklands of London made it clear; “no munitions must sail. No guns, aeroplanes, shells, bombs. Take no heed of cowardly politicians. With peace, Russia will light a beacon for the world.”

On 20 May, Dublin dockworkers followed the lead of their London equivalent. Refusing to handle British military equipment, Irish dockworkers introduced a new form of resistance into the country, which would quickly be adopted by railwaymen in the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. Writing in his memoir Forth The Banners Go, the trade unionist William O’Brien recounted the tale:

…a member of the dockers’ section of the Dublin No.1 Branch came to see me late one evening. He told me there were two vessels coming to Dublin with munitions to be used in the war here. One of the boars had arrived and was ready to be started discharing first thing on the following morning. He said that he might be one of the casual dockers, hoping to be picked for this job.

The man was a Citizen Army veteran of the Easter Rising, not particularly unusual in the docklands of Dublin. 1916 veterans included Tom Leahy, who had fought in the rebellion with the Irish Volunteers, but transferred to the ICA in the aftermath of the Rising. He recalled that throughout 1917 and 1918:

The work went on – making train wrecking tools, hand bombs, and everything that would be handy and useful when required. Several British naval vessels came to the dockyard for repairs – as our firm was on the Government list for such – and several raids were made on these vessels for arms when most of the crew were ashore.

When news of this proposed radical action was brought to O’Brien’s desk, he informed the visiting docker that he would raise it with Thomas Foran, General President of the union. The following day, the men standing around waiting to begin work were told that the work was not to start. The munitions strike had begun.

On hearing of the political action at the Dublin docks, the second ship was then diverted for Dun Laoghaire. Here, the military were on hand to unload its cargo, but when it arrived at Westland Row station, workers there refused to handle the goods. This, as Padraig Yeates notes in his masterful study of Dublin in the period,upped the temperature considerably. While the dockworkers were casual workers who could be reallocated elsewhere, the railwaymen were permanent employers and members of the separate National Union of Railwaymen.

The Freeman’s Journal shows the goods which Dublin dockers refused to offload.

In Britain, large sections of the working class movement responded favourably to the actions of Dublin dockworkers, though there was no sympathetic action. From John Maclean, the Scottish socialist firebrand, came words of praise and hope; ” Irishmen now refuse to supply the Army of Occupation with the ammunition that may be used to kill themselves when off industrial duty. This is surely the most sensible thing Irishmen have ever done in their history of toil and trouble. Irish Labour may call an Irish General Strike to force the withdrawal of troops from Ireland.”

In the following days, the action taken at the docks and Dun Laoghaire would be replicated elsewhere. The Freeman’s Journal reported on 24 May that “Yesterday afternoon some men at Inchicore were ordered to take a train-load of wagons containing ‘goods’ from Amiens street to Thurles, from which place the ‘goods’ were to be distributed to three other centres. When it became known that the wagons contained munitions disembarked at Kingstown the men refused to work the train.”

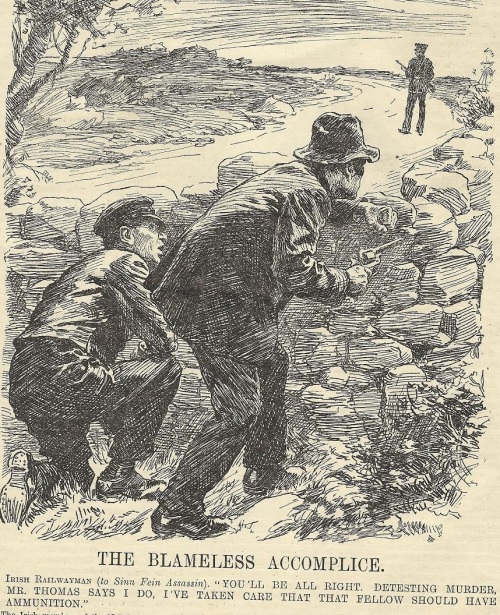

To sections of the conservative press, the behaviour of dockers and railwaymen was scandalous. The ever reliable Punch illustrated news produced a sketch in a June 1920 edition showing an IRA gunman hiding behind a rural wall, joined by a railway worker, or “the blameless accomplice.” The “Sinn Féin assassin” and the worker were conspiring hand in hand in the eyes of Punch. Still, the condemnation was nothing compared to The Irish Times at home, who believed that the workers involved were challenging “the fundamental security of the state and the fundamental rights of employers.”

A brave stand that began on the docks of Dublin spread nationwide, largely thanks to the militancy of railway workers. From arms in storage, the strike was widened to include the carrying of men holding arms representing Crown Forces. One Irish Volunteer, also employed at Mallow train station, recounted being dismissed from his job in his statement to the Bureau of Military History, noting that “when eventually 19 men had been dismissed for the same reason, the O/C Mallow decided to take the stationmaster prisoner and to detain him for a time.” The strike has real potential to create such tensions in work forces across the country.

The munitions strike was an effective tactic, proven by the infuriated responses to it from the upper-echelons of the British military and political class. In Westminster, Hamar Greenwood thundered that “no government can allow railways subsidised out of the pockets of the taxpayers to refuse to carry police and soldiers.” Likewise, in his Annals of an Active Life, Sir Nevil Macready, Commander in Chief of Crown Forces, acknowledged the tremendous difficulty the munitions strike created for the movement of men across the island.

Some £120,000 was subscribed to support men victimised for their participation in the strike, but in the absence of sympathetic strike action in Britain, and with increasingly vicious physical assaults on railwaymen, the Irish leadership felt increasingly vulnerable in the dispute, which eventually wound-down in December. In November, the Government began closing rail lines, including the Limerick to Waterford and Limerick to Tralee lines,as well as trains into Galway city, which certainly instigated a fear among the public that the Irish railway system could be shut down in its entirety.

The British approach to the crisis was to present the railwaymen as acting under duress. A bogus “order issued to railwaymen in Ireland and signed by the Ministry of War of the government of the Republic of Ireland” was produced, though dismissed outright by the report of the Irish Trade Union Congress, which insisted that “the railwaymen acted from the beginning of their own initiative, and were supported by the National Executive, by the Trade Union movement, and the country generally. They dictated their own policy independent of any instructions from any authority outside the Labour Movement.”

As both an industrial action and an example of mass civil disobedience, the munitions strike is a part of the story of revolutionary Ireland which is deserving of a place in this on-going Decade of Centenaries. Working class militancy across the island of Ireland, from the (largely Protestant and Unionist working class) Belfast Engineers Strike of 1919 to the Limerick Soviet, demonstrated the power of organised labour here clearly. In refusing to load or carry the weapons of war, both dockers and railwaymen demonstrated a unique form of opposition to the British occupation of Ireland.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

[…] and the day the Volunteers stole pigs set for export, May Day during the War of Independence, the Munitions Strike (the centenary of which is fast approaching) and the Bachelors Walk […]