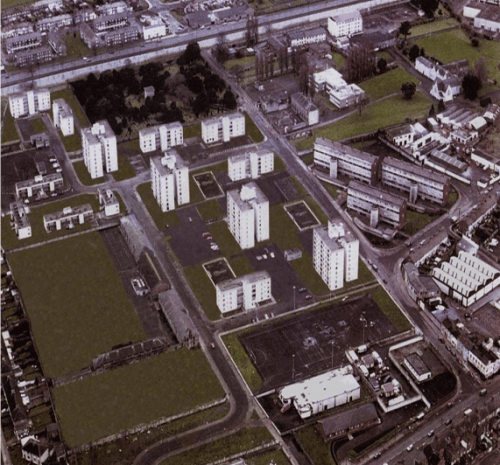

Keogh Square, Inchicore, 1960s (Dublin City Public Libraries Digital Collections)

With the departure of the British Army from Inchicore’s Richmond Barracks and the birth of the Irish Free State, the barracks was renamed in honour of Tom Keogh. One of the ‘Twelve Apostles’ and a trusted member of The Squad, the assasination team within the IRA’s Dublin Brigade assembled by Michael Collins, Keogh had played an active and important role in the Irish revolution. Killed in September 1922 during the subsequent Civil War, the naming of the barracks was a form of commemoration, but the military life of the barracks was short following the birth of the state.

Only weeks into 1922, the press were pondering if former British barracks could be utilised for housing. The Irish Independent wrote:

The buildings of the married quarters in most of the barracks might be utilised for housing families and relieving congestion while a proper housing scheme is being put into operation. The sites also offer scope for industrial establishments, and for such the buildings could be used without much remodelling.

By 1924, working class Dublin families were living in what was now known as Keogh Square. Four years later, it was reported that “248 families now are housed in the barrack building…and 218 families in houses recently built on a thirteen-acre field adjoining.” Given the history of the site, those who lived there became known as ‘Barrackers’.

History has not been kind to Keogh Square. In 1969, as the St. Michael’s Estate scheme prepared to open in its place, the demolition of the old homes of Keogh Square was described as “sounding the death kneel for the old world and symbolising the new decade of progress.”

The scheme is remembered today as a place which had a tremendous sense of community, but which was also among the most deprived working class housing schemes in the country. Initally, the converted barracks space had been considered decent with regards public housing, but conditions worsened as the scheme grew. The Dublin Tenants Association in 1918 had deplored Dublin Corporation for builing what they termed “neo-slums” in the place of the old across the city, but Keogh Square was different. When initally converted, each flat contained its own toilet, a large living space and a kitchen. Still, things gradually were left to decline. Local resident Nora Szechy, in her memoir of growing up in 1940s Inchicore, recounted that “it was a converted soldiers barracks to give housing to the poor. It was a dark, dilapidated tenement, which smelt of poverty and decay.”

Conditions in Keogh Square were regularly discussed in the press in the decades following independence. In April 1933, there was widespread coverage of the refusal of tenants to pay rent in protest at conditions, with residents organising themselves into the Keogh Square Residents Association. In 1957, Frank Sherwin T.D went as far as to say, over-dramatically, the conditions were “a kind of concentration camp if you like”,language only matched by the Irish Press, who described it as “a warren of decayed houses, human despair, a seeming example of man’s inhumanity to man.”

The opening of St. Michael’s Estate, 1970.

Keogh Square made it to the late 1960s, a time of considerable change in public housing in Dublin. For many, the seven Ballymun towers, named in honour of the executed 1916 leaders, are the enduring memory of that time,but change was apace across Dublin. St. Michael’s Estate was an impressive scheme in scale, as four eight-storey towers and seven four-storey blocks would replace what had stood before.

The new buildings were architecturally striking,designed by Arthur Swift and Partners. Still, as occurred on the otherside of the Liffey with the Ballymun scheme, there were critics who maintained services were inadequate. In her excellent recent study, Housing, Architecture and the Edge Condition: Dublin is building, 1935 – 1975, architectural historian Ellen Rowley quotes one 1960s voice as stating that “in Ireland, by and large, the struggle has not been to create neighbourhoods but merely to build homes. This is roughly parallel to producing automobiles without building hard surface roads.” Just as in Ballymun, the St Michael’s Estate housing scheme – and Keogh Barracks before it – is now a memory. The excellent Richmond Barracks museum and exhibition space includes reconstructed homes from both Keogh Square and St Michael’s Estate.

Architectural Survey, 1971. Digitsed by brandnewretro.

Aerial view of the former St Michael’s Estate. Dublin City Council.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

Reblogged this on Paddoconnell's Blog.

[…] 3. The Opening of St. Michael’s Estate, 1970. Source: Fallon (2019, […]