Sixty years ago, thirty-eight young IRA recruits from Dublin and Wicklow were arrested at a training camp. The raid took place in May 1957 while the group were drilling in the Glencree Valley near Enniskerry in County Wicklow.

Amongst those picked up were Sean Garland (1934-2018), Seamus Costello (1939-1977) and Proinsias De Rossa (1940-). The average age of the three men was just nineteen.

The arrests occurred a year into the ill-fated Border Campaign (1956-62).

The addresses of the men arrested offer an interesting insight into the backgrounds of those individuals involved.

Traditional Northside working-class areas like East Wall, Whitehall, Arbour Hill and Finglas are well represented. While south of the Liffey, the neighbourhoods of Inchicore, Ballyfermot and Crumlin in the South-West are particularly prevalent.

There are also a few addresses that stand out as not being representative of the stereotypical working-class IRA Volunteer including Dartmouth Square in Dublin 6, Tivoli Terrace in Dun Laoghaire and Islington Avenue in Sandycove. Ballsbridge also initially jumps out but further research reveals that Turner’s Cottages, where was one of the arrested men lived, was a rare working-class “slum” in the heart of Dublin 4.

Anthony Gill and Sean Garland lived less than a minute walk from each other in the North Inner City. Seamus Fay and Eamonn Ladraggan were neighborours on Merchant’s Road in East Wall. While brothers Patrick and Phil O’Donoghue gave the family address in Ballyfermot.

Northside Dublin:

- Sean Garland, 7 Belvedere Place, Dublin 1

- Anthony Gill, 555 North Circular Road, Dublin 1

- Partholan O’Murchadha, 1 Leinster Avenue, North Strand, Dublin 3

- Eamonn Ladraggan/Ladrigan, 19 Merchant’s Road (Bothar na Gannaide)*, East Wall, Dublin 3

- Seamus Fay, 55 Merchant’s Road (Bothar na Gannaide)*, East Wall, Dublin 3

- Seamus Doran/O’Dorain, 31 Sullivan Street, Arbour Hill, Dublin 7

- Patrick ‘Paddy’ O’Regan, 1 Goldsmith Street, Phibsboro, Dublin 7

- Seamus O h-Eadaigh, 110 Falcarragh Road, Whitehall, Dublin 9

- Patrick McLoughlin, 183 Larkhill Road, Whitehall, Dublin 9

- Proinsias De Rossa/Frank Ross, 14 The Rise, Glasnevin, Dublin 9

- Martin Shannon, 46 Griffith Drive, Finglas East, Dublin 11

- Padraig MacBhardaigh, 126 Glasnevin Road, Dublin 11

* Thanks to Stephen Donnelly who originally suggested that this was a misspelling of Bóthar na gCeannaithe (Merchant’s Road) which checked out.

Southside Dublin:

- Liam Healy, 22 Luke street, off Poolbeg Street, Dublin 2

- Tadhg Connellan (Tim Conlon), [22] Turner’s Cottages, Ballsbridge, Dublin 4

- Donal O’Shea, ?, Dartmouth Square, Dublin 6

- Sean Ryan, 1 Spencer Street (South), South Circular Road, Dublin 8

- Gordon O’Holain/Hyland, 17 McMahon Street, South Circular Road, Dublin 8

- Thomas Montgomery, 25 Wolseley Street, off Donore Avenue, Dublin 8

- Peter Pringle, 17 Woodfield Cottages, Inchicore, Dublin 8

- Michael Mann, 57 Tyrconnell Road, Inchicore, Dublin 8

- Patrick O’Donoghue, 95 Lally Road, Ballyfermot, Dublin 10

- Phillip O’Donogue, 95 Lally Road, Ballyfermot, Dublin 10

- Eamonn Mac Aonghusa, 178 Landen Road, Ballyfermot, Dublin 10

- Liam O’Rourke, 2 Thomond Road, Ballyfermot, Dublin 10

- Desmond ‘Des’ Webster, 50 Curlew Road, Drimnagh, Dublin 12

- Frank Delaney, 150 Benmadigan Road, Goldenbridge, Dublin 12

- Seamus/James Fagan, 171 Windmill Park, Crumlin, Dublin 12

- Sean O’Nolan/Nolan, 67 Bangor Road, Crumlin, Dublin 12

- Bernard S. Ryan, ?, Tivoli Terrace, Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin

- Liam Egan/Mac Aodhagain, 3 Islington Avenue, Sandycove, Co. Dublin

Wicklow:

- Desmond Byrne, 41 O’Byrne Road, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Michael Fortune, 5 Brennan’s Parade, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Daithi O’Ceallaigh/Kelly, ?, Adelaide Road, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Joseph McElduff, 20 Beach Road, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Seamus Costello, Roseville, Dublin Road, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Seoirse Doyle, Killincarrig, Greystones, Co. Wicklow

- Patrick Phelan, Kilquade, Co. Wicklow

- Proinsias Wogan, Atha na Scarlien, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow

Peter Pringle recalled the raid in his 2012 book ‘About Time: Surviving Ireland’s Death Row’:

In May 1957, while on a weekend training exercise, I was among thirty-eight volunteers who were surrounded and arrested by armed detectives. We were on a night trek along the Glencree Valley in County Wicklow. During the night, I noticed the lights of a lot of traffic on the roads above us on each side of the valley and knew from my hiking experience and my familiarity with the area that this was very unusual.

My alarm bells went off as I wondered what trucks might be doing on those quiet roads, all travelling in one direction in the middle of the night. I instinctively felt that we should leave and move up to the high ground above the road. I brought this to the attention of those in command of our column but they chose not to act.

When we reached the head of the valley with daylight coming on, we found that we were surrounded by armed detectives. I have no doubt that the traffic I had observed was the Garda and that that they had been informed of our location that night.

We were taken into custody to the Bridewell, a Garda station and holding centre in Dublin. We were each charged under Offences Against the State Act, 1939.

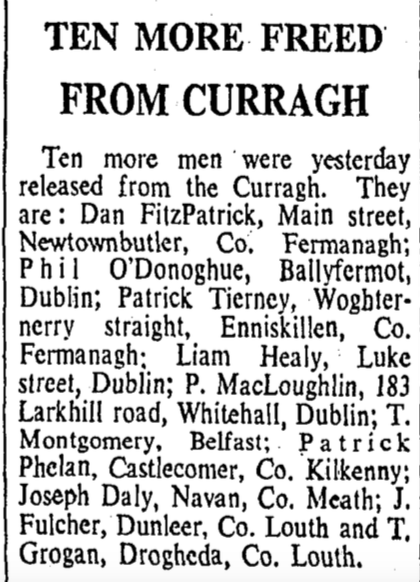

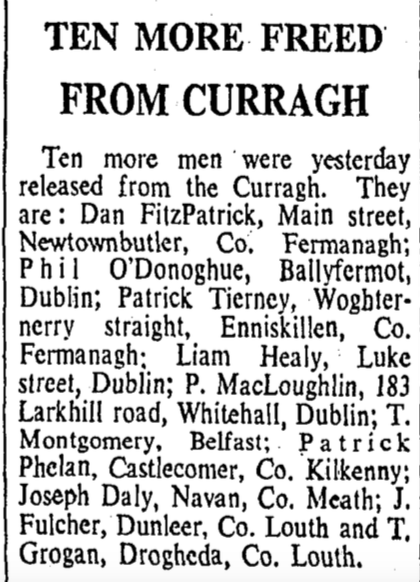

The men were charged with Section 32 of failing to give an account of their movements at a specific time and with membership of an unlawful organisation under Section 21. All of the accused men were remanded on bail at £25 each. The Irish Times (7 June 1957) reported that each man was sentenced to two-months imprisonment with hard labour. After this, most of the men were interned in the Curragh camp for a further two years.

What happened to the men?

Earlier that year, Sean Garland, Paddy O’Regan and Phil O’Donoghue were among fourteen volunteers involved in the Brookeborough raid during which volunteers Seán South and Fergal O’Hanlon were shot dead.

Garland became a leading figure in the Official Republican movement and was still active with the Workers’ Party until his death in 2018.

O’Regan was active with the Republican movement throughout the 1960s.

O’Donoghue was active throughout the 1970s with the Provisional IRA and later became National Organiser of the 32 County Sovereignty Movement.

His brother Patrick O’Donoghue was sentenced to six months in 1960 when he was caught with a .45 Webley revolver and six rounds of ammunition found in a drawer in a house he was in with Tony Hayde.

Seamus Costello was also involved with the Officials until he broke rank and helped form the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) in 1975. He was killed by a member of the Officials in 1977 as he sat in his car on Northbrook Avenue, off the North Strand Road in Dublin.

Proinsias De Rossa took the Officials side in the 1970 split and was active with the Workers’ Party until 1992. He became the first party leader of Democratic Left, a moderate wing of the party that split, and later merged with the Labour Party in 1999.

Martin Shannon was up in court again in 1961 for being a member of an ‘unlawful organisation’ and was later involved in the Official IRA. He was also editor of the United Irishman newspaper for a period in the 1960s.

Peter Pringle, father of left-wing Independent TD Thomas Pringle , became active with the Official IRA and later the IRSP/INLA for a short period in 1975. He was blamed for being part of a bank robbery in 1980 during which two Gardaíí were shot dead near Loughglynn in County Roscommon. He always denied any involvement in the crime and his conviction was overturned, due to discrepancies in the evidence, by the High Court in 1995 after serving 15 years.

Liam Egan/Mac Aodhagain, and Seamus Doran/O’Dorain were up in court again in 1961 when they were arrested with Liam Boylan and Thomas Mac Golla. Ammunition was found and they also failed to give accounts of their movements.

If you have any further information on any of the other individuals, do let us know.

19 February 1959.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.