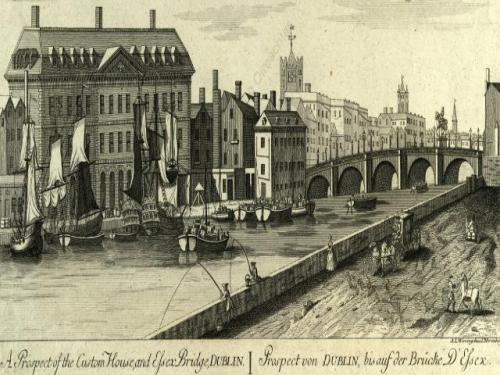

The Custom House (illustration by by James Malton)

The architect James Gandon (1743-1823) is today synonymous with Dublin. While he worked in other cities, and was born in London’s New Bond Street, his most celebrated works are to be found here. From the Four Courts to parts of the historic Parliament building on College Green, and from Kings Inns to the Rotunda Assembly Rooms, his work is a reminder of the style of the Georgian period that transformed Dublin.

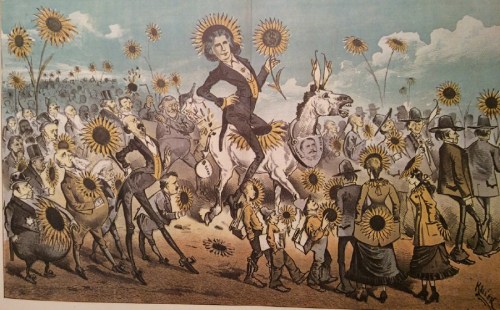

His first project in Dublin was undoubtedly his most controversial. While the Custom House is today recognised as a Dublin landmark building, the very prospect of its construction infuriated Dubliners who believed it would shift the entire axis of the city and negatively effect their own incomes. So controversial was the development, that Dublin workers (dismissed in contemporary accounts as ‘rabble’) would force their way onto the site of the development, led by the firebrand “populist patriot” James Napper Tandy.

Moving the Custom House:

The earlier Custom House at Essex (now Wellington) Quay.

Before Gandon’s Custom House, an earlier one could be found at Essex Quay, more or less at the site of Bono’s Clarence Hotel. Constructed in 1707, it was plagued by numerous problems, including the fact large vessels had difficulty reaching it thanks to the presence of a large reef known as Standfast Dick that proved a nightmare for anyone navigating the Liffey! As Maurice Curtis discusses in his recent history of Temple Bar, other problems included the fact that large vessels often had to use smaller craft , known as ‘lighters’, to unload cargo owing to difficulties in navigating up the Liffey, and the building itself was problematic, with its upper floors discovered to be structurally unsound in the early 1770s.

By 1773, plans were afoot to address the problem, with the powerful Revenue Commissioner John Beresford leading the campaign for a new Custom House to be constructed further eastwards. He proposed a new and enlarged development, though almost immediately the proposals were met by protest. As Joseph Robins notes in his history of the Custom House, “the proposal was opposed by a variety of individuals who feared their interests would be damaged by any shift in the location of commercial activity. Petitions against the project were presented by the merchants, brewers and manufacturers of Dublin, and by the city Corporation, but the government decided in 1774 to go ahead with the move.”

James Gandon arrives in Dublin:

The architect selected for this development was the Londoner James Gandon, grandson of French Huguenot refugees who had fled religious persecution. Gandon had already been awarded the Gold medal for architecture by the Royal Academy in London, and was in considerable demand beyond these shores; the Romanov family had attempted to lure him to St Petersburg around the same time as the Custom House controversy in Dublin.

When Gandon arrived in Dublin, he was kept a virtual prisoner by Beresford. His biographer Hugo Duffy has written of the real fear that gripped Beresford, writing that Gandon’s suspicion of the whole project “must have been heightened when he realised the opposition was so violent as to keep Beresford in a state of anxiety lest it became known that the architect had arrived.”

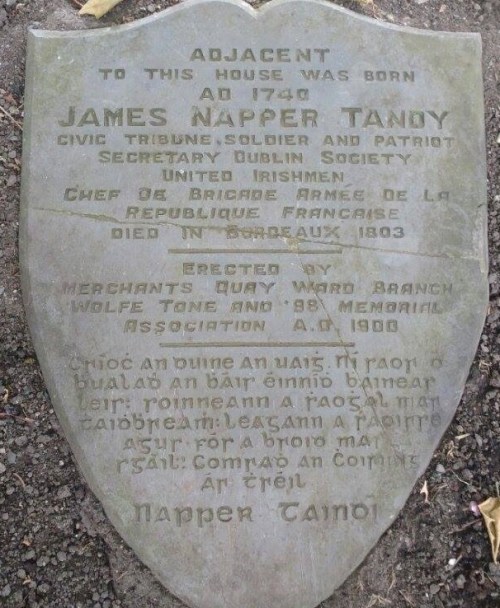

The primary figure that stood between Gandon and the new Custom House was James Napper Tandy, one of the great characters of the Dublin of his day. An ironmonger by trade, Tandy was elected to the City Assembly in 1777 and was a champion of the Dublin poor, not to mention a vocal campaigner against corruption in local politics. Later a founding member of the United Irishmen, many were unkind towards his appearance, with one observer of a political meeting he addressed remembering:

He was the ugliest man I ever gazed on. He had a dark, yellow, truculent-looking countenance, a long drooping nose, rather sharpened at the point, and the muscles of his face formed two cords at each side of it.

Memorial plaque to Napper Tandy, in the park at St Audeon’s, Cornmarket (Image: CHTM)

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.