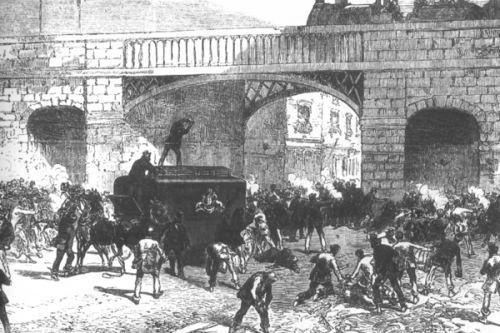

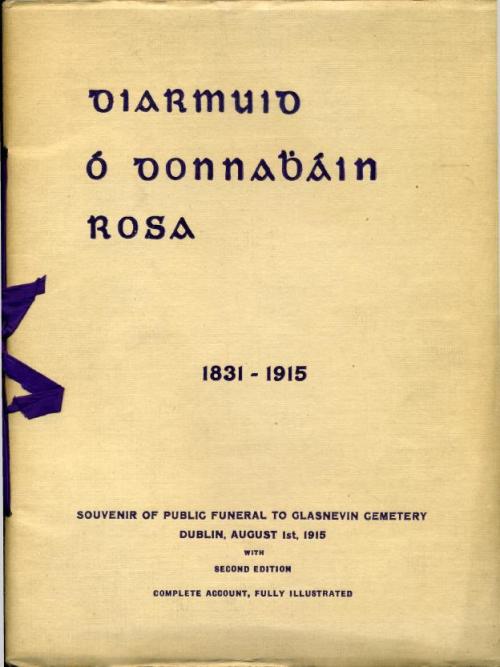

An eighteenth century illustration of bull-baiting (source)

Bull-baiting was stupid, and it was also undeniably dangerous. Given this, it is perhaps not surprising it was hugely popular in Dublin and other urban centres once upon a time! It has been defined as consisting of:

a bull being tied to a stake with a rope between 10 and 15 feet long. It was then baited – bitten, scratched and savaged – by dogs, usually bulldogs or mastiff especially bred for the sport..It appeal lay not only in its violence but also in the opportunities it presented for gambling on the performance of both the bull and the dogs.

As Paul Rouse has noted in his history of sport in Ireland, not all regarded this as a form of sporting entertainment; a letter-writer to the Freeman’s Journal in 1764 complained of the practices of bull-baiting and cock-fighting as being “inhumane entertainments”, while “in the early years of the nineteenth century, such views gained much greater currency”, as reformers sought to ban such ‘blood sports’.Still, for a moment in time it packed in the crowds to sometimes makeshift arenas in Dublin and other Irish cities. One source tells us that”the place for bull-baiting in Dublin was in the Cornmarket, where there was an iron ring, to which the butchers fastened the animals they baited”, but it appears to have happened in other areas too. Rouse points towards Smithfield as a popular location for those gathering to bet on the spectacle, noting that “not even the threat of-public whipping and imprisonment of its devotees could deter those who engaged in it.”

References to the stealing of bulls can be found in the oral history of the city, in songs and poetry. These words come from the popular Lord Altham’s Bull, written in the 1770s, telling the story of stealing a bull (or a ‘mosey’) for the purposes of bull-baiting:

We drove de bull tro many a gap,

And kep him going many a mile,

But when we came to Kilmainham lands,

We let de mosey rest a while

A writer named John Edward Walsh wrote a very entertaining and colourful book entitled Ireland Sixty Years Ago in the mid nineteenth century, which cast an eye back on some of the problems of Irish cities in decades gone by, including”bucks, bullies, rapparees, dueling, drunkenness, bull-baiting, idleness, abduction clubs and a thousand other degrading peculiarities which marked the higher as well as the lower classes.” Walsh took a particularly dim view of those who engaged in the sport, writing that:

The custom of seizing bulls on their way to market, for the purpose of baiting, became so grievous an evil in Dublin in 1779, that it was the subject of a special enactment, making it a peculiar offence to take a bull from the drivers for such a purpose, on its way to or from market.

On more than one occasion, violence erupted among crowds who had gathered to observe bull-baiting. On one occasion, dead bodies were left on the street when soldiers opened fire on a crowd who had gathered for a bull-bait in 1789 on Saint Stephen’s Day:

…a day devoted by the lower classes to relaxation and amusement, some of the tradesmen had purchased a bull, and brought him into a field, in the vicinity of the city, which was enclosed with a very high stone wall, and a gate which was kept shut. Some human persons, who considered bull-baiting as a cruel amusement, went to the Sheriff and required him to call out a military guard to put a stop to the proceeding. Vance, the Sheriff, complied.

His interference produced a riot. Oyster shells and pebbles were thrown by the mob, the soldiers retaliated by firing on the people. Many were wounded, four were killed. (source)

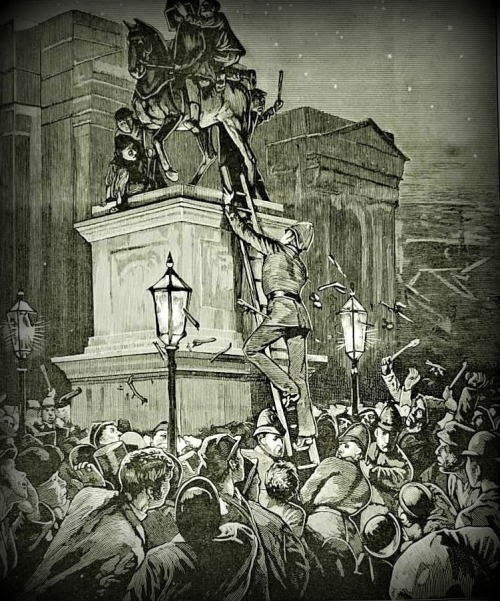

James Mahassey, Patrick Keegan, Ferral Reddy and an unnamed man lost their lives that day. In the aftermath of this sad affair, the families of those killed found an unlikely champion in the form of Archibold Hamilton Rowan, who was destined to become an influential member of the United Irishmen. The subject of a recent excellent biography by historian Fergus Whelan, Rowan was something of a champion of the poor and marginalised in Dublin, and he regarded the killings as an abuse of power on the part of the Sheriff and the authorities against the poor of the city. The Sheriff Vance was tried for the killing of Ferral Reddy, and in court Rowan made it clear he was personally “confirmed in the opinion of its being a most diabolical exercise of power.” The case was dismissed.

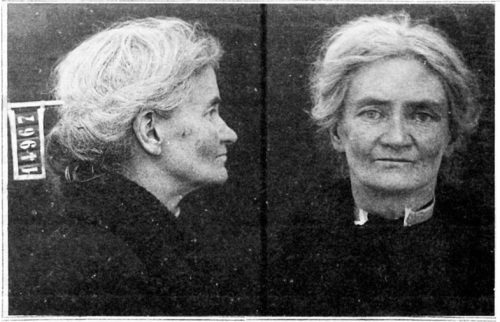

Archibald Hamilton Rowan, who sought justice for those killed in

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.