Joseph E.A Connell Jr.’s recent book, Dublin Rising 1916, is a remarkable resource that we’re going to be dipping into for a long time to come. Listing addresses in Dublin by postcode, it gives us an idea of the secret lives and histories of buildings that in many cases are very familiar to us. The buildings featured range from the iconic, such as the General Post Office, to the totally forgotten, like safe-houses in places like Cabra and Phibsborough.

Having dived into the secret histories of known places in the context of 1916, it got me thinking about the period that later followed, with the War of Independence (1919-1921), and the Civil War (1922-1923). The Bureau of Military History Witness Statements are one way of unearthing the hidden histories of places, and one that popped up a few times in various statements caught my attention; a bomb factory in the very heart of modern-day Temple Bar, active during the later stages of the War of Independence and into the early phase of the Civil War.

For the republican movement, carrying on the fight in the aftermath of 1916 involved great logistical difficulty. A defeated army lacks weaponry, not to mention the fact the Easter Rising had clearly demonstrated the need for better weaponry. Arms were procured in the period that followed the Rising in a number of ways. Sometimes, they were purchased abroad and smuggled into Ireland. On other occasions, they were seized during raids on police stations and barracks premises. In Dublin, they were even removed from visiting ships, like the American ship Defiance in 1918. The movement also depended on secret munitions factories, often hidden deep within legitimate places of business. The unenviable task of overseeing all of this fell on the shoulders of the IRA Director of Munitions.

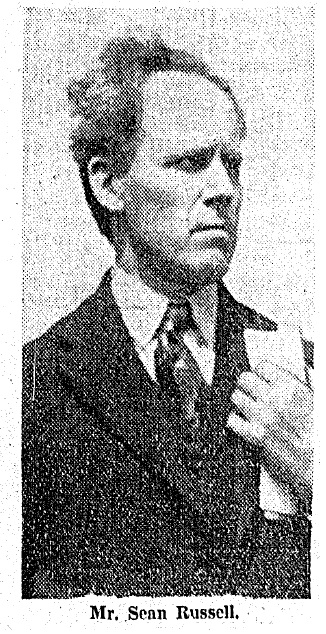

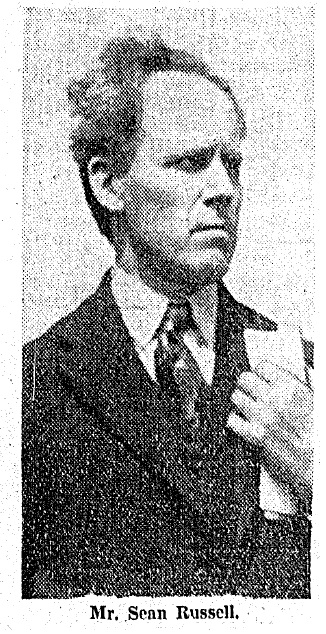

Seán Russell, a Dubliner born in Fairview in 1893, was a veteran of the Easter Rising who had been active with the Irish Volunteers from the time of their inception in 1913, and he is central to this story. By the time of the War of Independence he was a respected member of the IRA General Headquarters Staff (GHQ), and in 1920 he became the Director of Munitions for the body. He would later prove an important figure in the IRA of the 1920s and 1930s, serving as quartermaster general of the organisation from 1926 to 1937 and playing an active role in reorganising the body after its Civil War defeat. A deeply controversial figure today, he is primarily remembered for his later time as Chief of Staff of the IRA in the late 1930s, during which he orchestrated a disastrous and short-sighted bombing campaign of British cities. He also attempted to procure support for the organisation from both Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany in the 1920s and the 1930s, something that has led to repeated vandalism of his Fairview statue.

Seán Russell in the 1930s. He died in August 1940 on board a German U-Boat, having attempted to secure German assistance for the IRA.

Seán Russell became IRA Director of Munitions in the aftermath of the death of Peadar Clancy, a 1916 veteran who had become second-in-command of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA, and who was shot in Dublin Castle on Bloody Sunday, November 1920.

As Director of Munitions, Russell would have been acutely aware of the need for munition and bomb factories. What he didn’t have, according to fellow 1916 veteran Thomas Young, was the required technical or engineering knowledge. Young recalled that “I can’t say that this appointment had the approval of any member of the munitions staff, as Seán Russell had no engineering ability but considered himself, by virtue of his appointment, to be in a position to instruct and direct all munition workers.” Patrick McHugh, another member of the IRA’s munitions team, felt differently towards the appointment, remembering that “Sean and I got on well together. Our ideals were identical and although he had little technical knowledge of work in hand he left the production entirely to my discretion and always introduced me as his assistant and appointed as his deputy whenever he was absent.”

Oscar Traynor, later a Fianna Fáil Minister and Football Association of Ireland President, remembered that Russell stepped into the role quickly, as “a tremendously keen Volunteer”, who “had an extraordinary bent for organising and establishing matters of this kind.”

Before Russell, the movement was utilising a munitions factory at 198 Parnell Street “underneath the bicycle shop of Heron & Lawless”, but the eyes of the law came onto this site, and it became very clear that the work needed to be spread across the city after it was raided. Seán O’Sullivan, a munitions worker who had first joined the republican movement in Manchester in 1916, remembered that raids upon the Parnell Street factory made it redundant:

The munitions factory in Parnell Street was again raided in November, 1920, at night. The whole area was cordoned off. The military and auxiliaries remained on the premises the whole night apparently with the intention of capturing the staff when they arrived in the morning. A young fellow who had left his bicycle there for repairs, called that morning to collect it. When he saw the auxiliaries inside, he made an effort to run away from them. They opened fire on him and wounded him. That gave us the warning as Parnell Street was crowded when we arrived near the premises. None of us knew who was inside as a few of us had our own keys. We kept outside until we collected all the staff and got rid of our bicycles, mixing in the crowds. They seized everything, took away the plant and the premises were closed down. It was our idea at the time that they had only stumbled on to this through an area raid.

Munitions worker Patrick McHugh recalled that “I informed him [Russell] of our requirements regarding a foundry etc., and expressed the view that we should, as far as possible, scatter our work and duplicate premises so that we should not have a recurrence of Parnell Street.” McHugh claimed that within a week, Russell had sourced a new facility for the making of weapons at Crown Alley. This was the Baker family ironworks.

Today home to a Starbucks, the Bad Ass Cafe and The Old Storehouse among other businesses, Crown Alley is a bustling street in the heart of tourist-centric Temple Bar. In 1920 it was a very different place, located in what was still primarily an industrial district. Directly opposite the Telephone Exchange, a large imposing building still there today, was Baker’s Iron Works. It stood where Temple Bar Square is today, beside the Bad Ass Cafe. McHugh recalled inspecting it with Russell:

With Seán I inspected premises owned by Mrs. Baker facing Telephone Exchange which was under military guard. Mrs. Baker was running a small engineering and blacksmith business with her son, Paddy, in charge and a younger son in office. The premises suited our needs and she agreed to allow us more space in the general machine shop which we could partition off for machining grenades…. None of Mrs. Baker’s staff were in I.R.A. and it is a great credit to them that the presence of foundry and work done there was never disclosed to anyone.

There were a number of other such factories established across the city at this time, ensuring that a repeat of the disaster on Parnell Street would be avoided. Yet while dividing the workload between various munitions factories was a good idea, situating one right across from the Telephone Exchange at Crown Alley would have raised some eyebrows.

The Telephone Exchange was under British military occupation, owing to an eagerness that it not fall into rebel hands. in 1916, the rebels had planned for the occupation of the important communications centre, but in the chaos of the week it had gone unoccupied. It was too important a facility to be left unguarded now. Still, as munitions worker James Foran remembered:

They had sentries marching up and down on the roof of their building as we were going in and out, and we were never caught. I got paid while I was in Crown Alley. It was a full-time job and we were there for a couple of months. I was paid £1 a week, or maybe it was £1 a day. I think it was £1 a day. I was there for two or three months and finished up at the Truce.

RTE Stills image of Crown Alley before the modern development of Temple Bar, 1970s. The carpark on the right, opposite the Telephone Exchange, is where Baker’s ironworks once stood. (Image ownership: RTE)

McHugh’s entertaining Witness Statement details how a furnace was acquired for use in the Baker premises, as “try as we might we were unable to produce sufficient heat to melt iron” without acquiring a new one. These issues were resolved, and by March 1921 the munitions factory was well and truly in operation.

This particular munitions factory specialised in the part-production of grenades and landmines, with one munitions worker recalling that “we made there casings for hand grenades and fittings for mines.” Foran recalled that the grenades would be taken away in sacks, and that:

I never noticed how many grenades we turned out. They used to come twice a week and take three or four sacks of them in the car – not full bags. Seán Russell was in charge of us… It was marvellous the way we got away with it, we were very lucky. We were never raided. All the other fellows working there in the usual way at the usual foundry work never gave us away.

An idea of quantity comes from Frank Gaskin, who claimed that when the pieces moved on from Crown Alley to another munitions factory, “we were able to turn out two or three hundred grenades per day.” The product was constantly moving, from one factory to the next:

Finished grenades were brought direct to O’Rourke’s Bakery, Store Street, where all filling was done. Firing set castings were delivered to 1 and 2 Luke Street where machining and screwing was done. Strikers were taken to Percy Place for pointing ,safety levers were taken to Mountjoy Square where assembling of firing set was done.

Oscar Traynor, who provided an in-depth statement to the Bureau of Military History (National Library of Ireland)

Not alone were the IRA capable of producing huge numbers of grenades at this time – they were producing grenades of a much greater quality to what they had earlier relied on. According to Oscar Traynor:

In the course of time very great improvements were made in this particular type of weapon. Apart from the fact that the grenades were made larger, the explosive material was also greatly improved. The old complaint from which Volunteers suffered previously, that of throwing a grenade and having the experience of not seeing it explode, was almost eliminated. This aspect of the Volunteers’ armament developed a greater confidence in the fighting men of the various units.

The work of making grenades at Crown Alley continued right up to the Truce, and for those who took the Republican side in the Civil War, it was resumed. With the Civil War, the IRA found itself with a serious problem on its hands: former comrades in the Free State Army knew its modus operandi, and in many cases knew the location of such factories. McHugh remembered that the making of grenades and landmine parts “continued in these premises until taken possession of by Free State forces in March 1922.”

Mrs. Baker, who provided Seán Russell and his men with the use of her family ironworks at Crown Alley, was not a soldier, nor did she receive a pension or a medal. Yet, in her own small way, she was a vital part of the republican movement in the Dublin of her time, as were many others. As Patrick McHugh recalled:

Mrs. Baker, too, deserves great credit for the risk she took. She was not a young woman but had a great national spirit. Ireland’s soldiers needed help and she did not count the risk or cost, and was always in the best of spirit. Few women with a military guard facing their premises would take such a risk.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.