The Four Corners of Hell was the colloquial name given to the junction where New Street, Patrick’s Street, Kevin’s Street and Dean Street met in The Liberties, Dublin 8.

In the shadow of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, this crossroads was infamous for having a public house on each corner and the immediate area after closing time was legendary for its rowdy crowds and punch ups. Revelers from rival neighborhoods or families would pour out onto the streets when the pubs shut and would settle old scores and new disputes with their fists. Famed local cop Lugs Brannigan and his men based out of nearby Kevin Street Garda station would often have their work cut for them. Its heyday was from the 1950s to the early 1980s.

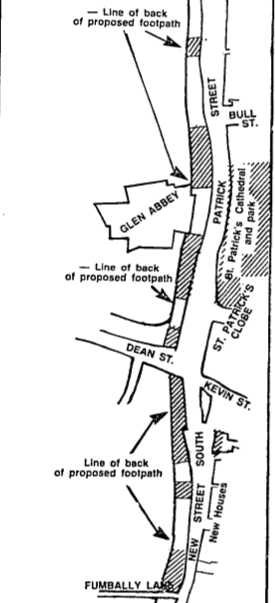

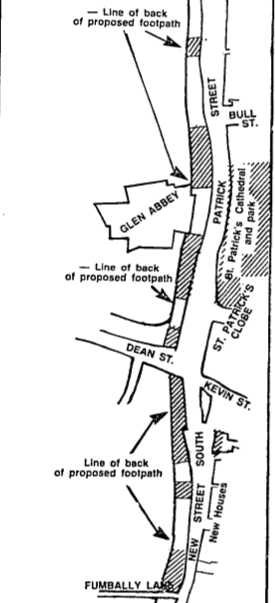

Illustration of The Four Corners of Hell. Credit – Sam (CHTM!)

The cross-roads is almost unrecognisable today now due to the demolition and road widening that occurred in the 1980s.

The shaded buildings were demolished by the council. Credit – Irish Times (13 May 1985)

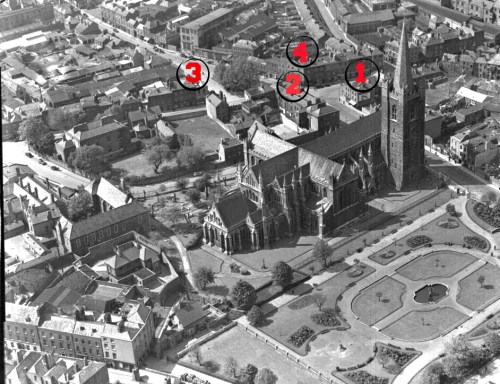

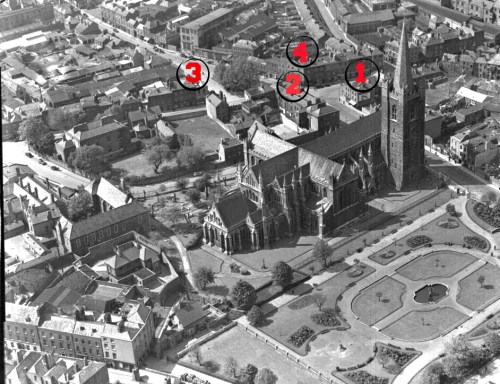

The four pubs were as follows:

1. Kenny’s

2. Quinn’s

3. O’Beirne’s

4. Lowe’s

Arial shot of the Four Corners of Hell, nd. Credit – ‘Growing up in the Liberties’s’ FB page

1. Liam Kenny’s on the corner of 49 Patrick Street and 9 Dean Street. Status – Building demolished and currently the site of a 99c store.

In the 1920s, the pub was run by a F. Martin and was known as Martin’s Corner. In February 1921, he was robbed at gunpoint by a man who made off with £10.

Publican Joseph Cody took over the premises around 1950. He had previously ran a pub at 21 Braithwaite Street in the nearby inner city area of Pimlico.

The Irish Times (12 January 1949) reported that two local men late one night the previous August had produced a pistol, forced themselves into the bar, asked for a dozen stout and whiskey and then shot and broke a bottle of wine and a mirror. Christopher Dunne (32) and Laurence Tierney (26), both of New Street, were found guilty of being in a possession of a firearm without a certificate. Dunne was sentenced to six months hard labour while Tierney was given a suspended sentence of nine months and bound to keep the peace for three years. The duo were found not guilty of possession of a firearm with intent to endanger life, conspiracy and armed robbery.

[The aforementioned Christopher Dunne was father of career criminal Christy ‘Bronco’ Dunne Jr. whose brothers were chiefly responsible for flooding the city with heroin in the late 1970s and 1980s].

On 5 October 1949, landlord Cody was fined £12 for having opened his pub during prohibited hours on April 10th (Good Friday) last. Twelve men were found on the premises by police. On 3 January 1951, now based in Dean Street in the Four Corners of Hell, Cody was again fined (£1) for allowing two women to drink in his bar after closing time.

On 21 November 1953, William Jackson (24) of Dowker’s Lane off Lower Clanbrassil Street was sentenced to nine months imprisonment for having stolen £7 from a cash box in Cody’s pub. Two others, Patrick Dandy (24) of Oliver Bond House and Thomas Claffey of Cashel Avenue, Crumlin were sentenced to 12 month’s imprisonment each.

On 14 September 1954, Kilkenny-born John Kelly (40) with an address on Cork Street was sentenced for four months imprisonment for assaulting Joseph Cody. The publican was shoved down the stairs, kicked repeatedly and received two black eyes in the attack.

On 9 August 1955 it was reported in The Irish Times that Mrs. Breda Cody, landlord Joseph’s wife, was brought before the District Court to “answer a complaint that she had taken a widow’s pension order book in exchange … for intoxicating liquor … and had failed to return it”. She was bound to be of good behaviour for two years. His husband was fined 10- for opening his premises on Good Friday on which the incident involving the pension book occurred. The family were going through a difficult patch. Mr. Cody admitted that:

… they were unable to make ends meet … (and) unable to pay a mortgage on the premises … They had not even a home now and were allowed by the purchaser of the premises to leave their furniture temporarily in them.

As far as I can tell, Liam Kenny took over the premises in 1963 and it was known as Kenny’s thereafter.

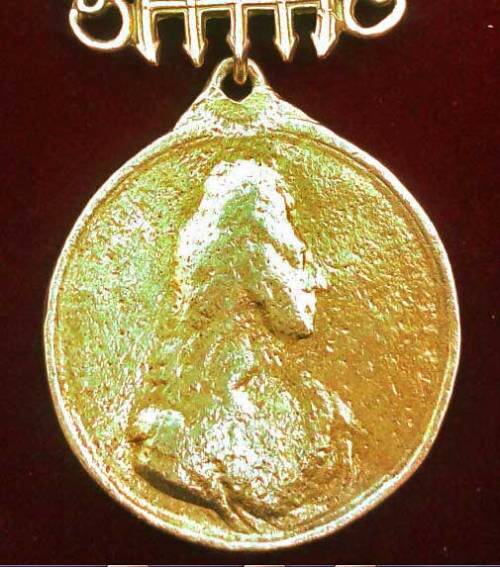

Liam Kenny’s, 1970. Credit – Dublin City Photographic Collection.

In the mid 1980s, a large area of Patrick Street and Dean Street was taken over and demolished by the Council using compulsory order. Patrick Street was to be widened and lands to the west of Patrick Street to be used for housing and development purposes. After years of stalled building work and planning objections, the seven-story apartment block ‘Dean Court’, comprised of 200 apartments in eight separate blocks, was put on the market in 1994.

The shop front where Kenny’s once stood was a Chartbusters video rental shop and is currently a 99c discount newsagent.

Where Kenny’s once stood. Corner of Dean Street and Patrick Street. Credit – myhome.ie

2. Quinn’s on the corner of 50 Patrick Street and 31/31A Upper Kevin Street. Status – Demolished, replaced by pub (now closed) and apartments.

P. Kenna, Tea Wine & Spirit Merchant 50 Patrick Street Dublin. c. 1900. Credit – @OldDublinTown

This pub was previously known as P. Kenna’s (see above), Kiernan’s (c. mid 1900s – 1920s), Cahill’s (1930s), Brannigan’s (mid 1940s) and Hamilton’s (late 1940s).

Continue Reading »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.