Since May 1816, Dubliners have been walking over what we now popularly know as the Ha’penny Bridge, though the bridge is formally known as the Liffey Bridge. Today, it carries an average of 30,000 of us from one side of the city to the other on a daily basis. Contemporary sources praised the bridge at the time of its unveiling, with one noting “it has a light and picturesque appearance, and adds much to the convenience and embellishment of the river”. At £3,000, the bridge was a costly replacement for a ferry service operated at the site previously, though costs were recuperated through the half penny toll, which would give the bridge its popular title. The mooring point for the historic ferry service on the south bank was as Bagnio Slip, with the historian Frank Hopkins noting that “the name bagnio is believed to originate from an early eighteenth-century Temple Bar brothel.”

The bridge in 1929, decorated to mark the centenary of Catholic Emancipation (Image: Dublin Tenement LIFE)

The idea for the construction of the bridge came from John C. Beresford, a member of Dublin Corporation, and William Walsh, the ferry operator. The bridge was to be christened the Wellington Bridge, in honour of the Duke of Wellington, victor of the Battle of Waterloo only a year previously and a native Dub. The Dublin Evening Post, barely able to contain themselves, reported on the opening of the bridge that:

A testimonial to the Hero of the British Army has at last been erected – a Testimonial at once creditable to the name with which it is to be honoured,greatly ornamented to the City of Dublin, and eminently useful to her inhabitants. We allude to the arch of cast iron thrown over our river, from Crampton Quay to the Bachelor’s Walk, opposite to Liffey Street, and which, we understand, with the express permission of the Illustrious Duke, is to be called Wellington Bridge. This Arch, spanning the Liffey, is one of the most beautiful in Europe: the excellence of its composition, the architectural correctness of its form,the taste with which it has been executed, and the general airiness of its appearance, renders it an object of unmixed admiration.

Interestingly, for something so associated with Dublin, the bridge itself was cast at Shropshire in England. Some Dubliners refereed to it not as the Wellington Bridge but rather the Triangle Bridge, which Frank Hopkins has noted was bestowed on it owing to the controversial background of John C Beresford, one of the men who had brought the bridge into being. Beresford was a former Tory parliamentarian who had twice sat in Westminster, but controversially was also active in a yeomanry which opposed the United Irish rebellion of 1798. His riding school premises in Dublin became synonymous in the mind of republicans with torture and the practice of flogging rebels upon a triangular scaffold.

The practice of torture was described in one nineteenth century history of Ireland thus:

The triangle was a wooden instrument made in the form of the letter A, about twice the height of a man, to which the person to be punished was tied, hands and feet, and lashed with wire cords knotted. In the midst of this torture, questions about the conspiracy were asked, and if the answers not satisfactory, the punishment was renewed!

In 1861 a letter writer to The Irish Times asked if the “miserable impost” of the fee to cross the bridge would ever be abandoned, insisting that “the general public are often obliged to go out of their way in going from one side of the city to the other to avoid the payment of the toll.”

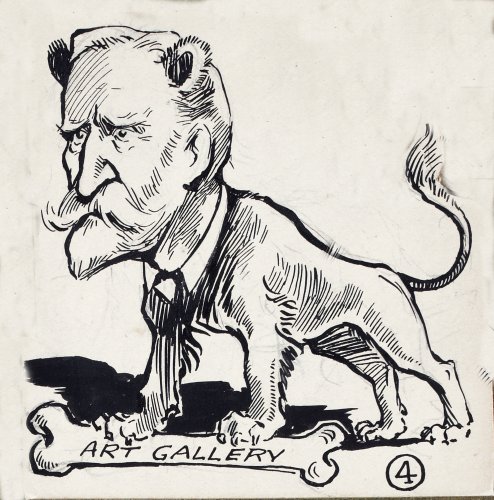

The controversy of the bridge and the Hugh Lane Gallery.

In 1913, a bitter dispute raged in the city regarding the ideal location for a gallery to house the Hugh Lane collection of paintings. One proposed location was a bridge gallery which would replace the historic Ha’penny Bridge. As historian Ciarán Wallace has noted, “strictly speaking, the dispute was about spending public money on a new art gallery spanning the Liffey, but the argument revealed deeper divisions.” Class tensions in the city were at an all-time high, with the Lockout on the horizon.

Hugh Lane commissioned the architect Edwin Lutyens to make drawings for a gallery, one of which is shown here. From January 1913 the influential business man William Martin Murphy was vocally opposing any such plan, claiming his opposition was firstly motivated by the desire that “he would rather see in the city….one block of sanitary houses at low rents replacing a reeking slum, than all the pictures Corot and Degas ever painted.”

Martin Murphy’s Irish Independent asked readers to take into the account “the effect of such a building in blotting out the fine view westwards from O’Connell Bridge, and how much out of harmony it would be with its surroundings.” Murphy wielded considerable influence in the city, not alone as a media tycoon but as president of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce. In the opposite corner were a wide variety of figures from the arts and labour movements, including Jim Larkin who moved a motion at Dublin Trades Council in support of the bridge gallery in July 1913, with Dublin on the edge of class war and the Lockout. Donal Nevin writes in his biography of Larkin that the tensions between the men were evident in this dispute, and Larkin proclaimed that Murphy “should be condemned to keep an art gallery in Hell.”

A cartoon that appeared in The Lepracaun in 1913, showing William Martin Murphy (Image: National Library of Ireland)

During a visit to his home city in 1913, George Bernard Shaw was asked what he personally thought of the idea of constructing a gallery spanning the river Liffey. His response was classic Shaw. “I admit that there is something romantic about a gallery thrown across a river on a fairy bridge, but the Liffey would take the romance out of anything!”

The Ha’penny Bridge lived to fight another day, as the bridge gallery proposal was abandoned in September. By then, the city was in the grips of class warfare.

Revolutionary toll dodgers in 1916.

One of my favourite stories involving the bridge concerns the Easter Rising of 1916, and a band of Volunteers who marched into Dublin from Maynooth in County Kildare, impressive by anyone’s standards! When these men arrived in the city they went first to the General Post Office on O’Connell Street, though they were later sent across the Liffey to the southside where men were urgently required. Thomas Harris recalled that “We were issued with two canister bombs; each and instructed how to strike a match and light the fuse and then fire them. We went down Liffey Street out on the Quays and across the Halfpenny Bridge. The toll man demanded a halfpenny!”

Another account of being stopped for the toll on the bridge came from J.J Scollan, a member of a small armed group named the Hibernian Rifles who took part in the Rising and who are often overlooked. Scollan remembered that

At 6 a.m. on Tuesday I received orders to get over to the Exchange Hotel in Parliament Street. We proceeded the Metal or Halfpenny Bridge – eighteen of my men and nine Maynooth men. Incidentally the toll man was still on duty on the Bridge and tried to collect the halfpenny toll from us. Needless to say he did not get it. No attempt was ever made to collect tolls on the bridge again [during the rebellion].

Given that this occurred a significant amount of time after the fighting had begun in Dublin, I can’t decide myself if the toll collector was the bravest or maddest man in Dublin. Dublin Corporation worried in the papers in 1916 if “in the event of being freed from tolls the bridge would be capable of satisfactorily bearing the increased traffic which would undoubtedly follow.” The toll expired in the winter of 1916, though the condition of the bridge seems to have deteriorated in the following years. A letter-writer to the Irish Independent complained in February 1917 of the “unpainted hoardings and worn out footways” of the bridge, and asked if it was”guaranteed to remain in this striking condition” until a new bridge was constructed. Sadly, with the restoration of the bridge in 2001, the turnstiles where the toll was paid were removed. This 1972 LP cover shows them as they appeared:

The bridge today.

In January 2001 it was reported in the media that a temporary bridge would be constructed across the Liffey, which it was expected would be used by up to 27,000 pedestrians a day, while a £1.6m restoration of the Ha’penny Bridge took place. The major restoration of the bridge has been seen as a great success, and for an idea of the scale of work and the attention to detail involved readers should see this page by Ryanstone, a firm specialising in architectural and monumental stonework. A half-hour documentary on the restoration project has been uploaded by the excellent Bridges of Dublin project. It shows the bridge as a covered structure during its restoration period.

Little passes under the bridge today. The tourist boat service, the Liffey River Cross, offers an interesting view of the bridge and the others in the city centre. In generations gone by the barges of the Guinness brewery would have been a very familiar sight passing under it on a daily basis, though they have been replaced by a modern fleet of trucks. Archive footage of a Guinness barge crossing under the bridge has been uploaded to YouTube:

In recent times a major annoyance for the City Council has been the presence of ‘love locks’ on the bridge, a trend popular right across Europe. Couples put padlocks on bridges, often bearing their names or initials, and frequently discard the keys into the rivers below them. In August of this year it was reported by the Evening Herald that the love locks will be removed once a fortnight.

In popular culture:

Not surprisingly, the bridge frequently appears in films and television shows depicting the city, as well as in music videos. Perhaps its most famous outing in a music video is Phil Lynott’s classic ‘Old Town’. A small plaque in Merchant’s Arch marks the fact that Lynott shot some of the music video on the bridge in 1982.

One of the best scenes I’ve found of it on the big screen is from Flight of the Doves, and my thanks to photographer Wally Cassidy for pointing me towards it. The 1971 film shows a Garda in pursuit of two youngsters, running across the bridge. The scene can be viewed here. Contrast the bridge then with what we have today and it’s easy to see why some Dubliners joke of being afraid to cross it in decades not long past!

Your memories and thoughts on the bridge are welcomed in the comment section below, as are corrections!

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.

This was a very interesting piece about the ha’penny bridge and well worth reading, thanks very much. Bob Navan

Late one night back in the 90s I was crossing the bridge and gave a quid to a beggar. In return he showed me that there are two of the old, large ha’pennies glued to the underside of the hand-level crosspiece railing, somewhere along the right hand side as you cross from north to south. Not sure if they’re still there, this would have predated the restoration work mentioned towards the end of the post.

Crossing the bridge as a child I always kept my eyes glued to the “snot green” waters visible through the gaps in the planks, holding tight to mam or dad’s hand so I wouldn’t slip through! The smell in summer and at low tides was just awful, thank goodness the sniffy Liffey has been cleaned up.

Really enjoyed this. Thanks. Keep up the good work.

Great article about the ha’penny bridge. There were some things in there that I didn’t know, so I really appreciate it.

Regards,

Claudiu

The bridge makes a memorable appearance in the final scene of the great 1958 film “Rooney” about a Dublin dustman (before bin collection in Dublin was privatised!).

Would George Halpin have had any input into the commissioning of the bridge? He was the Ballast Board’s Inspector of Works from 1810, a post to which Beresford may partly have sponsored him. At the time he was active in reinforcing the Liffey quays.

The great Dublin entrapentuer Hector Grey first started his business on the bridges north side with a stall of nick-naks.

I can remember the bridge very tricky to cross during winter months if there were frost and ice on it. Always need to be gritted.

[…] city had history played out a little differently. We’ve already covered the rather ambitious original plans to build Hugh Lane Gallery across the Liffey and the stunning landscape of Abercrombie’s “Dublin of the Future” but what of other […]

I have what I think may be the only photo of a horse and cart crossing the bridge.

[…] lads over at Come Here To Me! tell a great story about toll dodging at the bridge during the 1916 Easter Rising when a group of […]

The Ha’Penny Bridge is my absolute favourite Bridge, I can’t walk past it without stopping near the middle, looking over and taking a picture and now is a part of my history.

On July 14th 2013 myself and my boyfriend Gerry Whelan were walking across the bridge, the sun was shining and we did the usually of stopping to look over but this time was different when I turned around Gerry was on one bended knee, I couldn’t believe it, he asked me to marry him and of course while jumping around I said YES! To make things even better he had both of our families waiting on the other side so they rushed to greet us and got to witness a very special moment in our lives. We celebrated in The Temple bar pub that night. We will never forget the Ha’Penny Bridge. We are both from Tallaght but we moved to Vancouver, Canada in 2012 we are since married and now pregnant with our first child, due in August. We can’t wait to bring our child home to Ireland to visit and of course walk the Ha’Penny bridge for the first time with us. A very monumental part of Dublin/irish history but also my family history. ❤️❤️❤️❤️

Donna Jones Whelan

I crossed the bridge many times. It is DUBLIN.

Is the red carpet on over this weekend 20th-22nd May 2016????

my father painted this bridge many times Gus Hearne Decorators ❤

We read about Beresford and the ferryman, and casting in Shropshire, but who made up the specifications and design, and who constructed this bridge?

A short post on the 200th birthday celebrations at the bridge:

http://photopol.blogspot.ie/2016/05/happy-200th.html

I was sitting in a theatre in Berlin watching a play by Sean O Casey and saw a metal contraption, and thought I had seen that before. It was a replica of the entrance to the ha’penny Bridge. I’m a Dubliner.

Reblogged this on Galway Walks – Horrible Histories, Characters, Fun and much more and commented:

love to toll-man’s bravery or tenacity….great story

I always remember the wooden plank surface in the 1970s as being cross-wise….as in left to right as you walked across the bridge. However the ”

screengrab from Flight of the Doves showing the surface of the bridge as it appeared in 1970s” shows differently. Was i mistaken? Memory playing tricks on ? Maybe replaced and laid differently? Anyone remember them being cross-wise ?

[…] Ha’penny Bridge is without a doubt the most recognisable landmark in Dublin. The bridge itself was built in 1816 […]