With the rise of late night spots like the Vintage Cocktail Club and the Liquor Rooms in Dublin, there seems to be quite a market for cocktails at the moment. Interestingly, in the 1930s, cocktails in particular were targeted by the temperance movement here, who saw them as a threat because of their appeal to the middle class and female drinkers. Cocktails were routinely denounced by some within the religious community, often lumped in with jazz dancing, gambling and other such risks to faith and morals.

The temperance movement in Ireland has a long and interesting history, with Father Theobald Matthew central to its story. In April 1838, Father Matthew established the ‘Cork Total Abstinence Society’, which quickly became a nationwide movement. Individuals took ‘The Pledge’, which saw them pledge that “I promise with the divine assistance, as long as I continue a member of the teetotal temperance society, to abstain from all intoxicating drinks, except for medicinal or sacramental purposes, and to prevent as much as possible, by advice and example, drunkenness in others.” Thomas O’Connor, in his entry on Father Matthew for the Dictionary of Irish Biography notes that:

His crusade rapidly developed into a mass movement whose organisation, given its scale, was necessarily loose. For this reason, it never became a structured, national organisation. This may be how Father Mathew preferred things, partly, perhaps, out of a fear of losing control, partly out of the conviction that the movement was divinely directed.

Father Matthew is today honoured with a monument on O’Connell Street, which was unveiled by the Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1893, when huge crowds thronged the streets. After Father Matthew’s movement, the most significant to emerge was the Pioneer Total Abstinence Society in 1898, though it should also be noted that the movement for abstinence was not limited to Catholic organisations, with sizeable Protestant equivalents active both in Ireland and Britain.

A historic image of the Father Matthew monument, O’Connell Street. (Image Credit: National Library of Ireland)

At the 1938 centenary celebrations of Father Matthew, where Éamon de Valera presided in front of a packed room in the Mansion House, the Bishop of Kilmore warned that:

I am told of a danger, not from the good old glass of whiskey, but rather from a new thing I have heard of called the cocktail, and I am told is not workmen you will see going after cocktails, but people who have some claim to education and better positions in life than the workmen, and that these people are falling more or less into the cocktail fashion. I have not seen it with my own eyes, but I have heard stories, which, if they are true, make me very sorry. If what I have been told is true, we should get busy about it, and open the eyes of fathers and mothers to it.

The appeal of cocktails to young female drinkers was often identified by those in the temperance movement. At the annual meeting of the Irish Association for the Prevention of Intemperance in 1936, it was noted that “appalling revelations have been made in the press lately about cocktail and sherry parties even among business girls in their own apartments.” This well attended meeting, which was held at Bewley’s on Grafton Street, called for “the discontinuance of cocktails and the elimination of drinking clubs”, as well as seeking “the elimination of drinking at public dances.”

Of course, the very idea of a young woman drinking was shocking to many. At a packed meeting in the Theatre Royal in 1932, hosted by the Pioneer Temperance Association, “the advent of the modern girl” was discussed, with one speaker noting that “she loudly proclaimed herself a post-war creation. She was certainly a post-war sensation. The Irish Independent reported that “They knew the type he meant – a feather headed, immature creature who talked a lot of being independent, emancipated and ‘flap doodle’ of that sort.”

The Irish Times denounced the cocktail in 1932, warning readers that the cocktail “fulfils no useful function. It is supposed by the many to induce an appetite and to stimulate intelligent conversation; in fact, it absorbs the pancreatic juices and encourages cheap wit.” Never one to over-sensationalise things in the 1930s, the paper reported the belief of a doctor from Clare Mental Hospital in 1937 that “now that women have taken with avidity to tobacco and cocktails, one can visualise the most appalling results for the human race at a not far distant date.”

In 1930, one writer in the pages of the same newspaper wished a quick demise to the cocktail trend in Ireland, hoping that it would not alone be put to rest but would remain there. “May earth lie heavy on the cocktail, for its influence has been heavy on the earth”, he hoped. Today, it seems the cocktail has never been more popular.

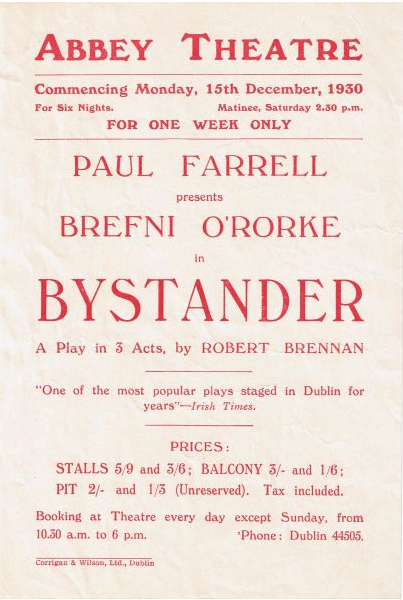

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.