Thomas O’Leary was a 22-year-old Dubliner and member of the anti-Treaty IRA when he was shot dead by the Free State Army in March 1923. There is a worn out monument, erected in 1933, to mark the spot where his body was found. We have previously covered the following Republicans who were killed during the final year of the Civil War – Noel Lemass, William Graham and James Spain.

With the 90th anniversary of his death around the corner, we thought it would be fitting to look at the short life of Thomas O’Leary, an IRA man attached to the 4th Battalion in Dublin. Thomas, or Tommy as he was known to his comrades, was found riddled with 22 bullets – one for every year he lived. There is a small, extremely worn Celtic Cross to mark the spot where his body is found in Rathmines. Perhaps this would be a good time to restore it.

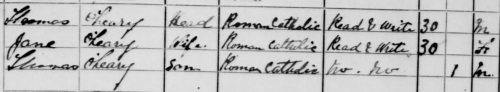

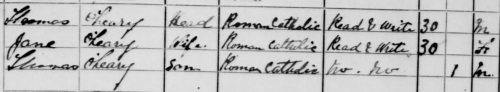

Thomas was born in December 1900 to Thomas O’Leary Sr. from Dublin and his wife Jane from Kildare. The 1901 census shows that the family were living at 372 Darley Street in Harold’s Cross. Thomas (30) was a glass cutter while his wife Jane (30) looked after their infant son. All were Roman Catholic.

1901 census return for the O’Leary family

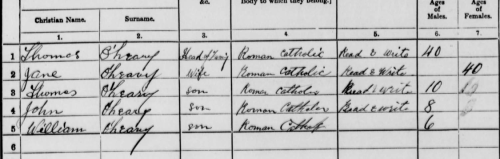

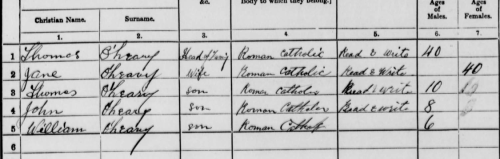

Ten years later the family had moved around the corner to 17 Armstrong Street. The 1911 census tells us that Thomas Sr. (40), still a glass cutter, and his wife Jane (40) were now living with their three sons. These being Thomas (10), John (8) and William (6). All three were at school.

1911 census return for the O’Leary family

Stephen Keys, a member of the IRA in Dublin from 1918 – 1924 mentions O’Leary in his Witness Statement :

Any time Tommy O’Leary, 0/C 4th Battalion Column, had a job, he would ask me to give him a hand with. it. We went out to Thomas St. for an ambush. There was a Free State private car coming up at the Church, with two or three officers in it. I was with O’Leary. The others fired at the car. I did not fire a shot. – BHM WS 1209

At the time of his death in 1922, Thomas O’Leary was listed as living at 17 Armstrong Street which corresponds with the census records. In the subsequent inquest, he was described as a “most respectable young man, a fine specimen of manhood, who, in the days of the ‘Black and Tans’, was a member of the IRA and did his duty to his country”. His brother testified that he had remained a member of the Republican Army after the split and was on active service in the months leading up to his murder. His mother revealed that he hadn’t been living at home since July 1922 and that he left his job as tram conductor on the Clonskeagh line in early 1923.

Deirdre Kelly in her book ‘Four roads to Dublin: the history of Rathmines, Ranelagh and Leeson Street’ points to O’Leary as the man who killed Free State politician Seamus O’Dwyer in his Rathmines shop in January 1923. However, Ulick O’Connor stresses in his biography of Oliver St. Gogarty that “members of the anti-Treaty group deny that O’Leary was associated with the O’Dwyer shooting”.

In the weeks leading up to the incident, the O’Leary home in Harold’s Cross was raided at least three times. His mother testified that during a search on the Sunday before, the soldiers told her that Thomas had until “Wednesday to give himself up, and, if they did not, she would fund him in Clondalkin or Bluebell shot; the next time he would be brought to her in a wooden box”. This is exactly what happened.

On the day of his death, his IRA comrade Stephen Kelly remember that:

O’Leary was after dyeing his hair red. We left the house and went over to the gardener’s tool house in St. Patrick’s Park which was used to store clothes before being sent down to the I.R.A. in the country. The man in charge of the tool house was sympathetic to the cause. O’Leary went back to Harper’s that evening and the Free State came along to raid it. They knocked at the door. One of the women was sick in bed. One of the Harpers called O’Leary and said “Go and get into the bed”. He got into the bed beside her. She was so stout, and he was so small and thin that he he was covered up in the bed beside her. He got away that time.

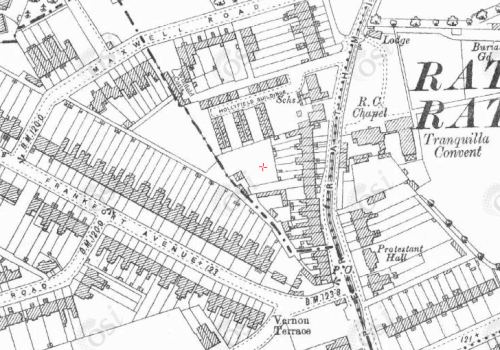

It was that night that the Free State finally caught up with him. On the 23rd March 1923, three lorry loads of Free State soldiers raided a house on Upper Rathmines and found O’Leary. This house was either number 82 or 86 as a woman at number 84 was reported as hearing knocking and a commotion “two doors away”.

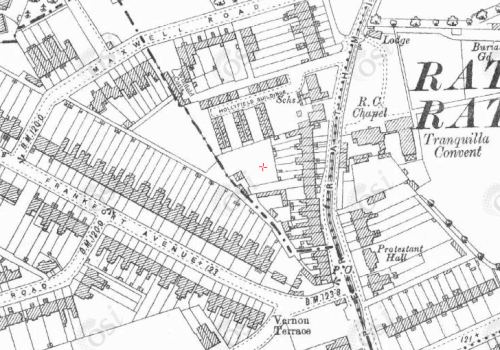

From reading all the contemporary newspaper reports, it can be accepted that O’Leary made a run for it and was caught by Free State soldiers. His body was found the following morning on the Upper Rathmines Road at the gates of the Tranquilla Convent.

Map showing the location of Tranquila Convent where the body was found

Dr. Murphy, House Surgeon of Meath Hospital said they found “22 circular wounds” in his body. These included:

Three … in the head … one in the region of the ear … four bullets under the skin … three wounds in the thigh … one on the right side of the chest

Near the body, they found eight spent automatic revolver cases, four large spent revolver cases and three small ones.

The Freeman’s Journal. 24 March 1923.

The jury at the subsequent inquiry came to the conclusion that O’Leary was “murdered by persons unknown … by armed forces, and that the military did not give us sufficient assistance to investigate the case.”. They ended by offering their “sympathy to the relatives of the deceased”.

In quite an interesting turn of events, poet and politician Oliver St. John Gogarty named O’Leary as the leader of the IRA men who kidnapped him on 20th January 1923. While having a bath after a long day’s work Gogarty, then a Free State senator, was taken away by six armed men. His biographer Ulick O’Connor wrote:

As he got into the car, the revolver was pressed hard into his back. ‘Isn’t it a good thing to die in a flash, Senator’ one of the gunman, said, as they sped out along the Chapeliziod road.

Gogarty was held in an empty house on the banks of the Liffey, near the Salmon Weir. On the pretext of an urgent call of nature, he was asked to be taken outside where he then made the quite daring decision to jump into the River Liffey. Shots were fired at him as he swam away. He eventually made it to the police barracks in the Phoenix Park.

His exploits were celebrated in a popular ballad of the day, written by William Dawson, which ended as followed:

Cried Oliver St. John Gogarty, ‘A Senator am I’

The rebels I’ve treicked, the river I’ve swum, and sorra the word’s a lie’.

As they clad and fed the hero bold, said the sergeant with a wink:

‘Faith then, Oliver St. John Gogarty, ye’ve too much bounce to sink’

While he got the dates slightly mixed up (O’Leary was killed a couple of months, not a couple of days) after his kidnapping, Gogarty is obviously referring to him in his autobiography:

“My kidnaping would not have been believed had the government boys not found my coat. A few days later a man called with a bullet, evidently from a .38, its nose somewhat bent. It was dug out of the spine of the ringleader who had raided my house and carried me off. O’Leary was his name. He was a tram conductor on the Clonskea line. He had died to a flash shrieking inappropriately under the wall of the Tranquilla Convent in Upper Rathmines.”

In March 1933, approximately ten years later, IRA quartermaster general Sean Russell unveiled a small marker at the spot where his body was found in Rathmines.

Today, this marker is completely eroded.

The memorial, unveiled in 1933, to Thomas O’Leary at the gates of Tranquila Convent, Upper Rathmines Road. (Picture – Ciaran Murray)

With the 90th anniversary of his death next month, the National Graves Association might think about restoring it.

Close up of the memorial, unveiled in 1933, to Thomas O’Leary at the gates of Tranquila Convent, Upper Rathmines Road. (Picture – Ciaran Murray)

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.