(Previously we’ve looked at Dublin’s oldest established restaurants and the city’s first Chinese restaurants)

Italian restaurants have flourished in Dublin since at least the late 1930s. Some of the first and and most influential of these were:

The Unicorn at 12B Merrion Court (1938 – Present)

Originally based at 11 Merrion Row, it moved around the corner to Merrion Court in the early 1960s. Ran by the Sidoli family from Bardi for 57 years, it was taken over by Giorgio Casari in 1995.

In ‘The Book of Dublin’ (1948) it was described as offering “central European cooking and very good of its kind. A quiet place for a slow meal and good conversation. The clientele is cosmopolitan, literary or artistic.”

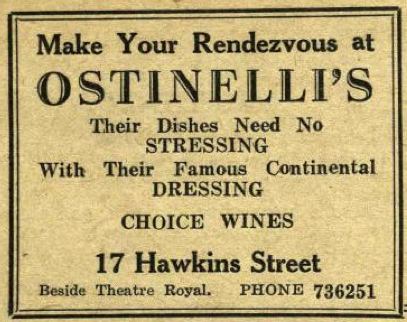

Ostinelli’s at 17 Hawkins Street (1945 – 1963)

Opened by Ernest and Mary Ostinelli, this restaurant was a popular spot for 18 years. A WW1 veteran, Ernest from Como in Italy came to Dublin in 1944 (after spells in Leeds and Belfast) and lived in Clontarf until his death at the age of 78 in 1970. Ostinellis was purchased by the Rank Organisation and demolished to make way for Hawkins House.

Alfredo’s at 14 Marys Abbey (c. 1953 – late 1960s?)

From Ospedaletti in Northern Italy, Alfredo Vido ran this popular late-night restaurant for nearly a decade. In Fodor’s Ireland guide (1968), it was described as “a place for an after-theater meal … in one of the oldest parts of the city and, as the location suggests, is on part of the site of a one-time abbey. Small, but has character and good food.” Ulick O’Connor, in February 1978 in Magill magazine, called it “Dublin’s first late-night restaurant … You banged on the door which looked like a knocking shop and a little spy hole opened like a Judas in a prison cell. If Alfredo liked you, he let you in and gave you a flower for your girl. When he didn’t like you – and a lot of people who used to flash the green backs he didn’t like – Alfredo just wouldn’t open the door.”

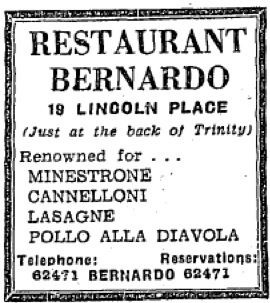

Restaurant Bernardo (aka Bernardo’s) at 19 Lincoln Place (1954 – c. 1991)

Moving to Ireland from 1952 from Rieti, Bernardino Gentile opened this restaurant with his brother Mario who later took it over. It was a popular spot for 37 years. It was described in 1998 by Patricia Lysaght as Dublin’s “first restaurant to offer an exclusively Italian menu using authentic Italian ingredients”

The Coffee Inn at 6 South Anne Street (1954 – 1995)

An Italian snack bar run by Bernardino’s other brother Antonio Gentile. Very popular with the art, student and music set of the 1970s and 1980s especially Phill Lynott.

Quo Vadis at 15 St. Andrew’s Street (1960 – 1991)

Also opened by the trendsetting Bernardino Gentile. He worked here until his retirement in 1991, he passed away in 2011 at the age of 91.

La Caverna at 18 Dame Street (1963 – early 1980s)

Ran by Bernardino’s other brother (!) Angelo Gentile who later opened Le Caprice Restaurant with his wife Feula. 1960s guide books describes how in La Caverna “dancing is also an added attraction”

Nico’s at 53 Dame Street (1963 – Present)

Long-established Italian, celebrating 50 years of business this year.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.