OBEY stickers spotted around Temple Bar today. Thanks to Luke F. for sending these snaps on.

For many many years, the shortest street in Dublin was Canon Street which was situated just off Bride Street near St. Patrick’s Cathedral. It was originally named Petty Canon Alley in the 1750s after the minor canons (members of the clergy who “assists in the daily services of a cathedral but is not a member of the chapter.”) of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The street had just one address, the public house of Messrs. Rutledge and Sons, and was such described in 1949 as the ‘shortest street in the world’ (Irish Press) and in 1954 as the ‘shortest street in Europe’ (Irish Times).

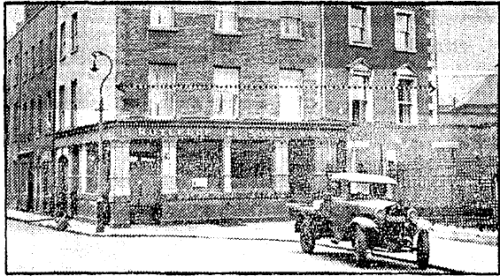

Canon Street can be seen in this old photo. Rutledge and Sons is the corner building in the bottom left hand side of the picture.

An image of the pub from the 1940s.

It also hosted, to rear of the street, the famous Dublin Bird market for hundreds of years.

The pub was demolished and so the street disappeared in the late 1960s to make way for the widening of Bride Street.

Today, it is generally accepted that Palace Street, just off Dame Street and a attached to Dame Lane is Dublin’s shortest street with only two addresses. No.1 is the French restaurant Chez Max and No.2 was the building that hosted the The Sick and Indigent Roomkeepers Society from 1855 to 1992.

Does anyone know of a shorter street?

Posted in Dublin History, Photography | 7 Comments »

The statues on each side of the Trinity College Dublin Campanile are well known to many, not only to students of the college but also to the many Dubliners who use use the college as a shortcut from Dame Street to Nassau Street.

On the left hand side, you find George Salmon. Salmon, as well as being a highly regarded mathematician and theologian, was a one time Provost of the institution, a deeply conservative figure who firmly opposed the admittance of women to Trinity. “If a female had once passed the gate …it would be practically impossible to watch what buildings or what chambers she might enter, or how long she might remain there” wrote the Board of Trinity College in 1895, capturing the spirit of the institution in Salmon’s time. It was somewhat ironic the first female student at Trinity College Dublin was to arrive soon after his death in January 1904. On the far side of the Campanile sits a fine memorial to historian W.E.H Lecky.

The George Salmon monument was first placed on the Trinity campus in 1911, though it didn’t sit in its current location at Parliament Square, but rather in the hall of the museum of the college. The sculpture was John Hughes, and The Irish Times noted at the time that the statue was carved of Galway marble. It was done in Hughes’ studio in Paris, based on photographs of Salmon. The statue has moved around Trinity on several occasions, beginning its life in the hall of the museum before being moved to the small lawn at the end of the library, near to the playing fields.

Yet to many, the statue was considered quite ugly. Writing in the letters pages of The Irish Times in January 1964, Owen Sheehy Skeffington defended the statue of Salmon, noting that “it is not a work of outstanding artistic distinction, but it has a rugged honesty that of the ‘warts and all’ type which accords well with the fearlessness and integrity of Salmon the man.”

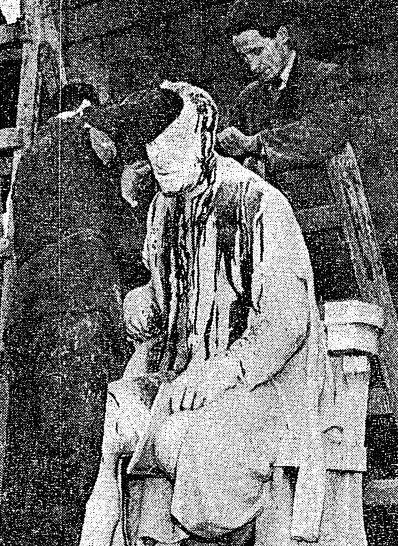

Some never saw the appeal of the monument however, and twice in the early 1960s Salmon’s monument made the national broadsheet papers following attacks upon it. In February of 1961, the monument was daubed with red paint and creosote. An official of the university remarked to The Irish Times that it was “probably some undergraduate prank”, but the paper quoted one student who passed them as saying “it was about time- and you can quote me on that.” In March 1963, Salmon was again singled out for attack, when black and red ink was flung upon it.

Salmon was only moved to his contemporary location in January 1964. It became the first monument placed in the front square of the college in nearly 30 years, seated on the far side of the Campanile from Lecky. The Irish Times noted that “some people who have looked at the statue are doubtful about the wisdom of placing it in the square” and went on to state that it “is considered by many to be rather ugly.”

With Salmon having insisted women would not enter his beloved university, he must have turned in his grave in October 2004. The Philosophical Society of Trinity College chose Salmon’s marble statue as an ideal location for a photoshoot for Kayleigh Pearson, the Phil’s first invited chair of the year. If her name doesn’t ring a bell immediately, I’ll spare you the Google: she was a model from mens mag FHM, Britain’s favourite ‘Girl Next Door’ no less. Trinity had come a long way.

Posted in Dublin History | 7 Comments »

The latest LookLeft has made it to the streets, and should be shelved at Easons branches nationwide by Saturday. The cover is the work of Luke Fallon, and though I’m a bit biased I think it’s a nice break with regards normal left-wing aesthetic and design. Below is the blurb for the magazine, but it’s worth mentioning from ourselves you’ll find a piece focusing on long-time Come Here To Me favourites ‘The Blades’ (see here for some of the posts jaycarax has given us on the band) and a piece on the upcoming ‘Decade of Centenaries’ and what it means to different people.

The new edition of LookLeft is out now. It is now expanded to 40 pages, proving that growth is possible even in an age of austerity. Highlights include:

* Ireland’s poll tax – building a mass non-payment campaign against the household charge

* Class Dismissed – Conor McCabe on the need for class to become a central part of political and social debate in Ireland

* Whose Decade is it Anyway? – Donal Fallon on the forthcoming centenary commemorations

* Street Wars – Fergus Whelan on family history and ideological battles on the streets of 1930s Dublin

* Making the Future Work – Alan Myler on workplace democracy and economic recovery

* Football and Revolution – David Lynch on Egyptian Ultras and political struggle

* Feminism’s New Dawn? – Leah Culhane on Irish feminist debates on the Slutwalk phenomenon

* Rebel with a Cause? – Interview with Patrick Nulty TD

* Not Even Our Rivers Run Free – Padraig Mannion on the water privatisation agenda north and south

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

Unlock NAMA, a fantastic campaign dedicated to the promoting the ‘access NAMA properties for social and community use and to hold NAMA to account’, are hosting a kick ass fundraiser on Saturday night in King 7, Capel St.

Warming up the night’s proceeding will be aurally pleasurable Prog band E5 Disconnect, indie pop punks Ghost Trap and crust ‘dolecore’ Twisted Mass.

Taking us into the wee hours will be Kaboogie! legend PCP, RAID’s gKB, Drum n Bass connoisseur Executive Steve (Tribe / Ancient Ways) and Monaghan’s No1. DJ of all time Welfare (Jungle Boogie/Subversus / Choonage) who has been tearing up house parties, raves and club nights with a cheeky smile since 2004.

Facebook event here. Sharing is caring.

Posted in Events, Music | Leave a Comment »

Here’s two new stories recorded by the lads behind Storymap, uploaded since my 3 minutes and 25 seconds of fame recently talking about Vonolel the war horse. A labour of love, Storymap has been documenting great Dublin tales from all corners of Dublin and both sides of the river.

Firstly, Liz Gillis, author of the recent excellent study of the Civil War in Dublin entitled ‘The Fall of Dublin’ with Mercier Press. Liz talks about Conn Colbert and Watkin’s Brewery during the Easter insurrection in 1916.

This weeks story features actor Val O’Donnell, as tells a great tale about ‘Myles na gCopaleen’ and his campaign over Andy Clarkin’s clock in the 1950’s.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Recently, and completely by accident, I stumbled across newspaper reports of the ‘opening’ of Dublin’s first escalator. It all struck me as a little bit Father Ted, with the Lord Mayor of Dublin on hand for proceedings. He then had the honour of being the first person in Dublin, and indeed the nation, to use an escalator.

Fine Gael politician James Joseph O’Keefe was the Lord Mayor of Dublin from 1962-1963, and then again from 1974-1975. On Monday, March 25th 1963 he found himself in Roches Stores on Henry Street to “inaugurate” over the unveiling of the first escalator in Dublin, at an event which made the front page of The Irish Times the following day.

The escalator extended from the basement to the ground floor and from there to the first floor, and the opening coincided with the Roche’s Stores Fashion Show. The Irish Independent ran the image below, which shows the Lord Mayor cutting the ribbon to proclaim the escalators ‘open’. The design of the escalators was carried out by Clifford,Smith and Newman of Limerick.

Patrick Lagan wrote lightheartedly of the event in The Irish Press the week after the escalator was deemed open, writing that he had always enjoyed the “uplifting experience” of hopping on an escalator in a London tube station, and that he felt they were built not only to be useful but indeed enjoyed.

Lagan went on to note that:

On Monday last the Lord Mayor of Dublin , Alderman J.J O’ Keefe was,as was only right, the first man to make the ascent. But he won’t be the last. Let me thank the people who run that big store for making it possible for myself and others to enjoy this purest of human pleasures without the trouble of having to go as far as Euston Station.

Posted in Dublin History | 8 Comments »

Where Were You?, the magnificent 304 full colour photo book on Dublin’s youth culture and street fashion published late last year, will be back in the shops on Thursday, April 12.

The first run sold out within weeks, so you’re advised to pre-order with Garry on the website here.

In the latest issue of History Ireland, Cllr. Cieran Perry wrote a fantastic review of the book which touched on issues of class and racism in Dublin’s 1970s punk and skinhead scenes.

Last October, I had the opportunity to interview the book’s editor Garry O’Neill which resulted in articles in Rabble (Issue 2) and Look Left (Vol. 2, No.8).

Posted in Dublin History, Music | 12 Comments »

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.