On Walworth Road today, just beside the Irish Jewish History Museum, a small plaque marks the birthplace of William Shields. Better known as Barry Fitzgerald, he was a world-famous actor and an Academy Award winner, winning the 1944 Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in Going My Way. The plaque makes no mention of his brother, the Abbey Theatre actor and Easter Rising participant Arthur Shields, who also knew Walworth Road as home for a time.

William Shields (Barry Fitzgerald) and Arthur Shields.

Arthur and William both achieved great success in their lifetimes. There has been a renewed interest in Arthur this year, with the centenary of the insurrection in which he fought. Famously, he retrieved his rifle from under the stage of the Abbey Theatre before taking part in the fight of Easter Week. Yet a hugely important and formative influence over the brothers, their father Adolphus Shields, remains a largely obscure historical figure. A pioneering figure of Irish trade unionism, and a key figure in the Fabian Society in Dublin, Adolphus was so respected by James Connolly that he told a young Arthur in the GPO, “I hope you will prove as good a man as your father.” Among other battles, Adolphus had played a prominent role in the fight of the eight hour working day in Dublin.

Adolphus Shields was born in Capel Street in 1857. He married a German woman, Fanny Ungerland from Hamburg, in 1881, and their relationship produced seven children. Adolphus belonged to the Church of Ireland, and his children were all raised in the Protestant faith. He was a printer by trade, but life appears to have been difficult for the large family for a period, as in the words of Arthur, “we were always having to move because nothing could be paid. There never was enough money in those days, and the family was big.” By 1911, things had improved, and the family were living in Clontarf. Despite being listed in the 1901 census as Church of Ireland, Fanny was now listed as an agnostic, while a daughter was listed as a Spiritualist.

1911 Census, filled in by Adolphus Shields.

Fearghal McGarry, in his recent and excellent study of the Abbey Theatre rebels of Easter Week, quotes from a source that provides great insight into Adolphus as a father and as a man:

Whenever they changed on private fencing that cut off what Papa knew to be public domain, to the great delight of the children, he would kick it down,pull it apart and set them to scattering the pieces.He was careful though to make the distinction between wanton destruction and concerned action to protect public rights.

Charles Sauren, a friend of Arthur Shields who would enlist in the Irish Volunteers with him in 1914, remembered that Adolphus was a “pioneer in the cause of Irish labour.” The late nineteenth century was a time of enormous change in trade unionism in these islands, as the emergence of a ‘New Unionism’ in Britain saw the organisation of unskilled and general labourers en masse, something that would be replicated in Ireland, most notably later by Jim Larkin. As labour historian Donal Nevin noted, the emergence of new mass trade union movements, as opposed to the ‘craft unions’ of old, “had its effects on the trade union movement in Dublin, notably in the setting up of a branch of the National Union of Gasworkers and General Labourers of Great Britain and Ireland…in March 1889. Adolphus Shields became the Union’s district secretary.”

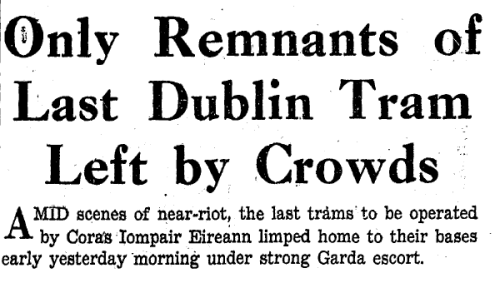

The battle for the eight hours’ day, reported in the Freeman’s Journal.

One campaign he seems to have been actively involved within was the battle for an eight hour working day, something Dublin gas workers achieved in 1890. The Freemans Journal reported in March 1891 that Shields spoke at a “large meeting of the workmen of the city at Beresford Place to celebrate the anniversary of the winning of the right hours’ day by the gas workers of Dublin.” Four bands were present, and there were resounding cheers for Shields when he spoke. The eight hour day was hard fought for, and not only in an Irish context. The Second International, representing the combined strengths and interests of many socialist and labour parties, had called on unions worldwide to demonstrate for the eight-hour day on May Day 1890.

Adolphus Shields addressed Ireland’s first May Day rally in that same year, speaking in the Phoenix Park. Labour meetings in the park could draw huge crowds; Fintan Lane has noted that one union demonstration in the park in the summer of 1890 was attended by about 10,000 people, as “six hundred coal-porters, accompanied by the Bray Brass Band, headed the procession from Beresford Place.” Shields used one speech in the park to attack Home Rule MP’s who had failed to support the Eight Hours Bill in Westminster, as “they talked a lot about the farmer, but they did not consider the interest of the men in the cities at all.” These Phoenix Park meetings drew some remarkable speakers, young and old. Among those to address a labour demonstration in the park was Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx. She told a crowd of thousands in 1891 that unions were “helping to do away with hatred and prejudices which it had been the object of capitalists to foster”, before she “spoke in favour of better wages and shorter hours for the working people.”

Eleanor Marx, who spoke at one of the Phoenix Park meetings. Adolphus Shields was a frequent contributor to trade union rallies in the park.

Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more. Click on the book for more.

Click on the book for more.